It is reason, and not passion, which must guide our deliberations, guide our debate, and guide our decision. – Barbara Jordan

In the gilded halls of America’s elite universities, financial firepower is both a symbol and source of dominance. Endowments—the great silent engines of academia—determine not only which students get scholarships but which schools can recruit Nobel-calibre faculty, fund original research, and shape public policy. At the apex of this order stands UTIMCO, the University of Texas and Texas A&M’s investment juggernaut, with more than $70 billion under management. Below, far below, exist the undercapitalised yet ambitious Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) of Texas.

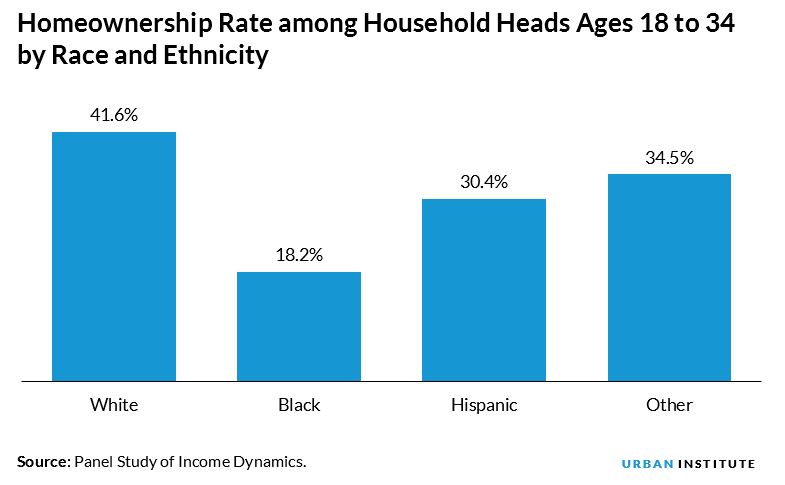

Two of the state’s largest HBCUs—Prairie View A&M University (PVAMU) and Texas Southern University (TSU)—have long histories, loyal alumni, and vital missions. What they do not have is institutional wealth. PVAMU’s foundation reported a modest $1.83 million in net assets in 2022. TSU’s foundation, better capitalised, holds $22.7 million. Combined, that amounts to just $24.5 million. For comparison, Rice University, less than 50 miles from either campus, holds an endowment north of $7.8 billion.

That yawning disparity matters. But it also presents an opportunity: a merger of the two foundations into a single, more potent philanthropic and investment entity. Done properly, it could reorient how Black higher education competes—not by appealing to fairness or guilt, but through scale, strategy, and institutional force.

A Rebalancing Act

To understand the potential of a PVAMU-TSU foundation merger, one must first grasp the dynamics of university endowments. Large endowments benefit from economies of scale, granting them access to exclusive investment opportunities—private equity, venture capital, hedge funds—often unavailable to smaller players. They attract the best fund managers, demand lower fees, and can weather market volatility without compromising their missions. Small foundations, by contrast, tend to be conservatively invested, costly to manage per dollar, and too fragmented to punch above their weight.

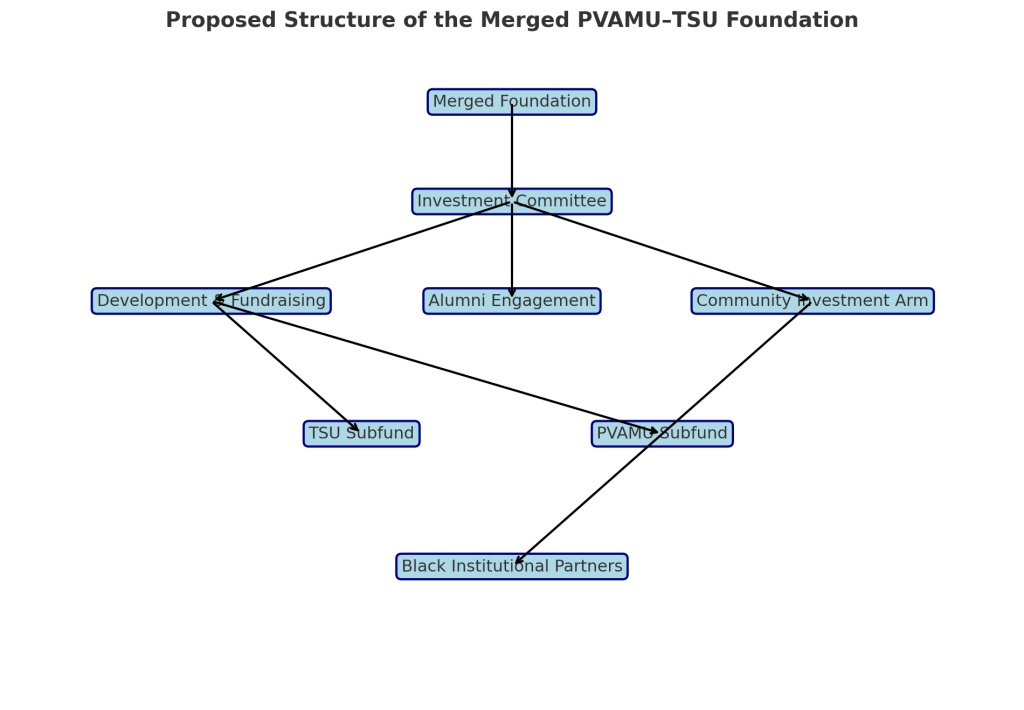

A consolidated HBCU foundation in Texas would be small compared to UTIMCO, but large relative to its peers. With a $25 million corpus as a starting point, the new entity could position itself for growth by professionalising its investment strategy, adopting a more ambitious donor engagement plan, and forming partnerships with Black-owned banks, family offices, and community institutions. Call it the Texas Black Excellence Fund, or perhaps, more simply, the TexHBCU Endowment.

To be sure, the legal and logistical barriers to such a merger are real. Foundation boards guard their autonomy jealously. Alumni pride can turn parochial. Governance models would need careful negotiation to ensure representation and avoid turf wars. But the arguments in favour are compelling.

The Power of One

First, a merger would cut overhead. Legal, accounting, auditing, and compliance costs—duplicated today—could be streamlined. A joint fundraising apparatus could create a single point of entry for corporate partners and high-net-worth donors. Branding efforts would gain coherence: instead of competing for attention, the institutions would stand together as a symbol of Black institutional unity and strength.

Second, scale invites leverage. A $25 million foundation cannot change the world overnight, but it can attract co-investments, engage in pooled funds, and perhaps even launch a purpose-driven asset management firm in the model of UTIMCO. If successful, this would be the first Black-led institutional investor of serious size in Texas—capable not only of managing endowment funds but of influencing broader economic flows across Black Texas.

Third, the merger would send a strategic signal to policymakers and philanthropic networks. It would say, in effect: “We are no longer asking for permission to grow. We are building the engine ourselves.” That tone matters. Too often, HBCUs are framed as needing rescue. A merged foundation flips that narrative. It becomes an asset allocator, a market participant, a builder of capital rather than a petitioner of it.

UTIMCO: A Goliath in the Crosshairs?

No one expects a $25 million fund to challenge a $70 billion behemoth. But that is not the point. UTIMCO’s dominance is as much political as it is financial. Its influence flows from its role as gatekeeper to resources, shaping everything from campus architecture to graduate fellowships. The merged HBCU foundation would not dethrone UTIMCO—it would decentralise power by becoming a second pole.

Indeed, the comparison may inspire mimicry. Just as UTIMCO serves multiple institutions, so too could a joint HBCU foundation. Prairie View and Texas Southern are only the beginning. Over time, the model could scale to include other Black-serving institutions across Texas and the South. This would amplify investment impact and accelerate institutional wealth-building.

Moreover, such a foundation could adopt an unapologetically developmental investment strategy. Where UTIMCO optimises for returns, the TexHBCU fund could optimise for both returns and racial equity—by investing in Black entrepreneurs, affordable housing, climate-resilient infrastructure, or educational tech. The dual mandate—profit and purpose—would not be a hindrance but a hallmark.

Regional Stakes

Prairie View sits on a rural hilltop. Texas Southern sprawls in urban Houston. But their communities are deeply connected—culturally, economically, demographically. A combined foundation could create regional development strategies that go beyond scholarship aid.

Imagine a venture fund seeding Black-owned start-ups in Houston’s Third Ward. A real estate initiative turning vacant lots into mixed-income housing for PVAMU students and local residents. A workforce development fund retraining returning citizens for green jobs across both cities. Each dollar invested becomes more than a balance sheet entry; it becomes a force for transformation.

This matters not just to students and faculty, but to the broader Texas economy. Black Texans make up 13% of the state population but own less than 3% of its small businesses. Educational attainment gaps persist. Institutional neglect deepens. The merger would not fix all this—but it would give the community a new tool for shaping its destiny.

Copy, Then Paste

If the model works, it would not stay in Texas. Southern University in Louisiana has multiple campuses and foundations that could benefit from consolidation. So does the University System of Maryland’s HBCUs. Indeed, the entire sector could adopt a federated endowment strategy—unified in purpose but distributed in governance.

HBCUs have long suffered from institutional atomisation. They are asked to compete individually in a system that rewards consolidation. Merging foundations is not just a finance play—it is a strategy for survival and sovereignty.

The Alternative: Stagnation

Critics may say a merger is too ambitious. That it risks alumni backlash or donor confusion. That it could take years to execute. But delay is itself a cost. Each year the foundations remain separate is another year of opportunity lost. Another year where millions in potential returns go unrealised. Another year where larger institutions deepen their lead.

PVAMU and TSU have histories to be proud of. But institutional pride must not become institutional inertia. A merger is not surrender—it is evolution.

In the long arc of higher education, moments of boldness define legacy. This is one of those moments. Two foundations. One future. Let the uniting begin.