Timidity does not inspire bold acts. – Dr. Mae Jemison

The college fair model is broken — at least for HBCUs. Here’s how alumni chapters can build a pipeline that starts long before a student ever picks up a brochure. Walk into any college fair in a major American city and you’ll find the same scene: rows of tables draped in school colors, stacks of glossy brochures, and admissions representatives competing for the attention of juniors and seniors who, by that point in their academic journey, have already largely made up their minds. For predominantly white institutions with billion-dollar endowments and national name recognition, the college fair model works well enough. For Historically Black Colleges and Universities, it represents a fundamental misalignment between the urgency of the moment and the passivity of the approach.

HBCU enrollment has seen encouraging upticks in recent years, but the long-term pipeline challenge remains real. Alumni chapters, often the most energized, locally embedded advocates for their institutions are still overwhelmingly operating in reactive mode. They show up to fairs. They host the occasional scholarship gala. They cheer at homecoming. What we are not doing, with nearly enough intentionality, is going to where the students are, years before those students are old enough to apply. That has to change. And the blueprint for changing it is hiding in plain sight.

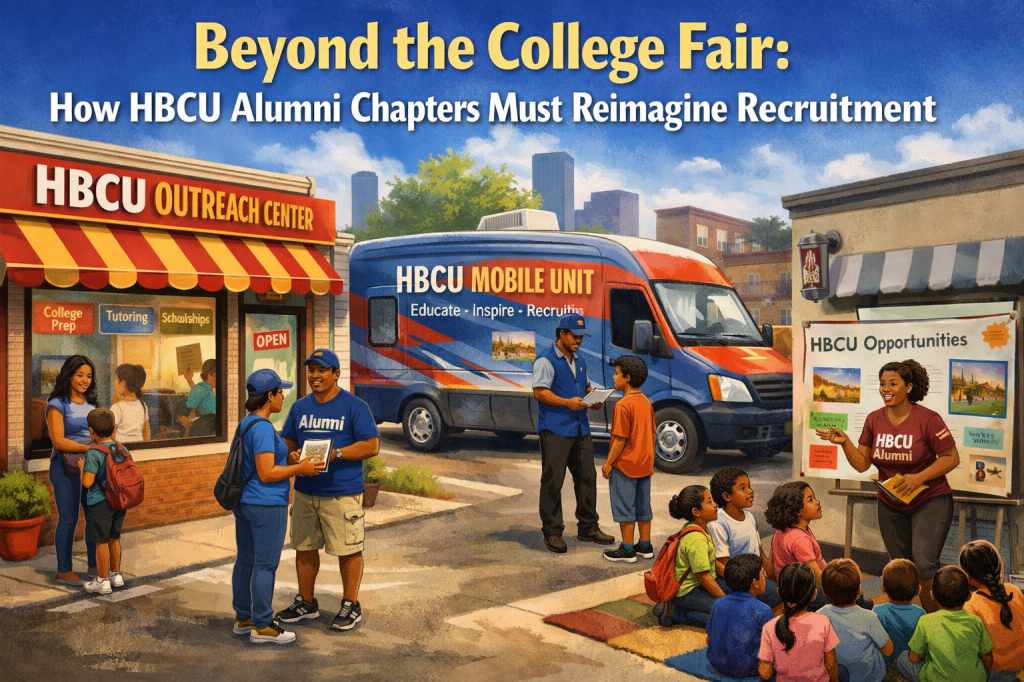

Imagine walking down a commercial corridor in Atlanta’s West End, Houston’s Third Ward, Baltimore’s Park Heights, the five buroughs in New York, or Chicago’s South Side and seeing a storefront with the colors and seal of a prominent HBCU. Inside, a welcoming space offers something radical in its simplicity: free help.

Help filling out college applications. Help navigating the FAFSA. Tutoring for high school students. Information sessions on academic programs, scholarship opportunities, and campus life. GED preparation for adult learners. GMAT and GRE prep for prospective graduate students. A community room where a kid can sit down after school and do homework, surrounded by images of Black excellence in cap and gown.

This is not a fantasy. It is a strategic infrastructure play that HBCU alumni chapters can begin building right now and the financial logic is stronger than many chapters realize.

Alumni chapters that have built up reserves, or that are willing to pool resources with neighboring chapters, should be actively exploring storefront leases in high-traffic African American neighborhoods. The cost of leasing modest commercial space in many urban corridors, while not trivial, is within reach for chapters with organized fundraising operations. More importantly, this model transforms the alumni chapter from a social organization into a community institution — and community institutions attract donors, partnerships, and long-term sustainability.

For chapters with the financial sophistication and appetite, ownership rather than leasing should be the goal. A storefront property that houses an HBCU recruitment and support center is also a real estate asset. It appreciates. It can be refinanced. It generates community goodwill that translates into alumni donations and corporate sponsorships. Forward-thinking chapters should be thinking about their real estate portfolio the same way a small nonprofit thinks about its balance sheet — as a long-term instrument of mission and sustainability.

But the case for ownership goes well beyond the chapter’s balance sheet. When an HBCU alumni chapter purchases a commercial property in a Black neighborhood, it is making a statement that is felt far beyond the four walls of the building. Vacant storefronts are one of the most visible symptoms of disinvestment in African American communities. They signal to residents, businesses, and young people that nobody believes in the block — that the neighborhood is somewhere to leave, not somewhere to build. An alumni chapter that acquires and activates one of those properties is doing something that no amount of college fair attendance can accomplish: it is demonstrating, physically and permanently, that Black institutional investment is real.

This is the chapter functioning as a community developer — not just a recruiter. The presence of a professionally staffed, well-maintained HBCU center on a commercial corridor raises the standard for the surrounding block. It attracts foot traffic. It gives neighboring businesses a reason to invest in their own storefronts. It signals to prospective residents and entrepreneurs that the community has anchors worth building around. Property values in the immediate vicinity benefit. The narrative of the neighborhood begins to shift.

Alumni chapters that think this way are not simply supporting their alma mater — they are exercising the kind of place-based economic power that Black communities have historically been denied. Every dollar that goes toward acquiring and improving a property in the community stays in the community. The chapter builds equity. The neighborhood builds stability. And the students who walk through that door every day see, in the most tangible terms possible, what organized Black investment looks like. That lesson alone is worth the price of the building.

Chapters that cannot yet afford standalone locations should explore co-location models: shared space with Black-owned businesses, community centers, or even jointly operated centers with two or three HBCU chapters that maintain separate branding but share overhead. A joint Virginia State-Morgan State-Cheyney recruitment center in a major metro is not just a cost-saving measure — it is a statement about the HBCU ecosystem as a unified force.

The single biggest reason community-based recruitment initiatives fail is that they are built on volunteerism alone. Volunteers are essential — but they cannot open the doors at 9 a.m. on a Tuesday, maintain records, follow up with prospective students, or manage institutional partnerships. A storefront that is going to deliver consistent, professional service to the community needs a full-time core team. It does not need to be large. It needs to be right.

The foundation of the storefront operation is the Executive Director / Center Director, a full-time salaried role that carries the weight of the entire operation. This person manages the relationship with the alumni chapter board and the parent institution, oversees staff, builds and maintains community and school district partnerships, and is ultimately responsible for the center’s recruitment numbers and programming outcomes. This is not an entry-level position. The ideal candidate has a background in higher education administration, community organizing, nonprofit management, or some combination of the three — and they are a proud, vocal HBCU product. Salary range: $70,000–$80,000 depending on market and chapter resources.

Supporting the director is a Recruitment and Admissions Counselor, a full-time role dedicated entirely to student-facing work. This person guides prospective students through the entire application process — from first contact to submitted application to financial aid completion. They manage the center’s student database, track pipeline metrics, and are the primary point of contact for high school counselors and community college advisors in the region. A background in college admissions or student affairs is ideal, and again, HBCU alumni status is a meaningful qualification. Salary range: $60,000–$68,000.

The third full-time position is a Financial Aid and Resource Navigator. The financial aid process is where more students fall out of the pipeline than anywhere else — not because they cannot afford college, but because the system is confusing, intimidating, and unforgiving of missed deadlines. This staff member specializes in FAFSA completion, scholarship identification, financial literacy education, and connecting adult learners with workforce funding and employer tuition benefits. They serve every lifecycle stage the center touches. A background in financial aid administration, social work, or community financial services is the right profile. Salary range: $60,000–$68,000.

These three full-time positions form the operational spine of the storefront. Beyond them, part-time staff and alumni volunteers extend the center’s capacity without extending its payroll. A part-time academic tutor or tutoring coordinator — ideally a current graduate student or recently graduated HBCU alumna — can run afternoon and evening tutoring sessions. Alumni volunteers with professional backgrounds in law, medicine, business, and education rotate through the center for workshops, panel discussions, and one-on-one advising sessions. A volunteer coordinator role, which can be managed by the Executive Director in the early stages, ensures that the volunteer corps is organized, scheduled, and recognized for their contributions.

The total full-time annual personnel cost for the storefront, including modest benefits, runs approximately $190,000–$220,000. That is a real number, and chapters should treat it as such when approaching their institution, corporate partners, and grant funders. It is also the number that separates a serious operation from a well-intentioned hobby.

For communities and schools that cannot easily access a storefront location, the chapter must come to them. This is where the concept of the HBCU mobile recruitment unit becomes a game-changer.

Alumni chapters should be looking seriously at purchasing used charter or transit buses and retrofitting them as mobile engagement vehicles. The cost of a used bus is often in the range of $30,000 to $80,000 depending on age and condition, with retrofitting adding additional investment. But the return in community presence, recruitment reach, and alumni chapter identity is enormous.

A properly outfitted mobile unit becomes a rolling admissions office. Equipped with laptops, tablets, printed materials, and onboard programming capability, the bus can park outside middle schools during dismissal, set up at community festivals and church parking lots on weekends, and roll through neighborhoods that college admissions representatives have never set foot in. It can run FAFSA completion workshops at community centers, host financial literacy sessions for parents, and bring the campus — virtually, through screens and presentations directly to families who may have never considered that a college education is within their reach.

A bus without a dedicated crew is a very expensive parking lot ornament. The mobile unit, to function as a true outreach vehicle rather than an occasional showpiece, requires its own committed staffing structure — lean but professional.

The non-negotiable full-time role is the Mobile Outreach Coordinator, who is simultaneously the unit’s program lead and its logistical engine. This person owns the deployment schedule, manages school district and community partner relationships, leads or facilitates on-site programming when the bus is in the field, and tracks every student interaction for follow-up and pipeline reporting. Critically, they serve as the bridge between the bus and the storefront — ensuring that students engaged in the field are handed off cleanly into the center’s formal services. This role requires someone who is equally comfortable presenting to a room of eighth graders, negotiating access with a school principal, and updating a CRM database. Salary range: $55,000–$65,000.

The second essential role is the full-time Commercial Driver / Logistics Coordinator. This is not simply a bus driver. The right person for this role holds a commercial driver’s license (CDL) and also takes ownership of vehicle maintenance scheduling, equipment inventory, and supply logistics for the unit. On deployment days, they are a visible, welcoming presence — often the first face a student or parent sees when approaching the bus. Many alumni chapters will find this person within their own membership: a retired transit worker, a logistics professional, or a veteran with transportation experience who is deeply invested in the mission. Salary range: $45,000–$55,000.

These two full-time positions are the core of the mobile unit. On high-volume deployment days — school visit days, large community events, or multi-stop weekends — part-time Recruitment Ambassadors supplement the crew. These are ideally current HBCU students or recent graduates who can speak authentically to the college experience, assist with application and FAFSA walkthroughs on the bus’s onboard stations, and engage peers in a way that no administrator can replicate. They are paid hourly and scheduled based on the deployment calendar.

The storefront’s Recruitment and Admissions Counselor and Financial Aid Navigator should also rotate onto the bus for targeted events — particularly FAFSA completion drives and high school senior nights — ensuring that students who need deeper guidance get it in the field, not just at a fixed location.

The full-time annual personnel cost for the mobile unit runs approximately $100,000–$140,000, excluding the bus acquisition and retrofit. Chapters that operate both a storefront and a mobile unit under one organizational roof — sharing the Executive Director’s oversight and administrative infrastructure — realize meaningful efficiencies. The combined full-time staff across both operations totals five to six people, with a total annual personnel investment in the range of $300,000–$400,000. That is a community development organization of real consequence, and it should be funded and governed as one.

The most important shift in mindset this article is calling for is one of timeline. HBCU alumni chapters cannot afford to think of recruitment as something that begins in 11th grade. The pipeline has to start much earlier — and it has to serve learners at every stage of life.

Head Start (Ages 0–5): Before a child ever sets foot in a kindergarten classroom, their relationship with learning and with the adults who shepherd it is already being shaped. This is why HBCU alumni chapters must engage Head Start programs, and why that engagement represents one of the highest-leverage opportunities in the entire pipeline.

Head Start is the federal early childhood program serving primarily low-income children ages birth to five, and Black children are among its most significant constituencies. According to the most recent federal program data, 29 percent of Head Start enrollment is Black or African American, non-Hispanic making it one of the largest organized points of contact with Black families in America at the earliest stage of a child’s development. Yet the program is dramatically under-serving the eligible population it is meant to reach: nationally, only 54 percent of eligible Black children are served by Head Start preschool, a gap driven in part by residential segregation and the uneven geographic distribution of Head Start centers.

That gap is itself an opportunity for HBCU alumni chapters. A storefront-based center located in a Black community can serve as a trusted navigator helping families find, apply for, and access Head Start services while simultaneously introducing those same families to the HBCU pipeline that begins long before a child can read.

The engagement strategy at this stage is not academic. It is relational. Head Start programs already operate with a strong family engagement model — approximately 378,000 adults volunteered in their local Head Start programs in a recent program year, of whom 295,000 were parents of Head Start children. Alumni chapters should be plugging into that existing network of engaged parents, not waiting for those parents to find them. Partnering with local Head Start centers to host family nights, read-aloud events, and college aspiration programming for parents creates touchpoints that are warm, community-rooted, and years ahead of any college fair.

The parents of Head Start children are also, frequently, prospective students themselves. Many are in their twenties or early thirties, may have some college credit, and are navigating the competing demands of parenthood and economic insecurity. An HBCU alumni chapter that shows up at a Head Start family event with information about degree completion programs, flexible scheduling, financial aid for adult learners, and the life-changing potential of an HBCU education is not just planting seeds for the next generation — it is recruiting for this one. The storefront’s Financial Aid and Resource Navigator is a natural liaison here, building relationships with Head Start family service coordinators who are already helping parents navigate social services and can add educational pathways to that conversation.

Alumni chapter members who are educators, social workers, pediatricians, or child development professionals should be the face of this engagement. Reading to children at a Head Start center, facilitating a workshop for parents on school readiness and early literacy, or simply being a visible, joyful presence in the community establishes the HBCU brand as one that cares about Black children from the very beginning not just when they are old enough to fill out an application.

Elementary School (K–5): The goal at this stage is not recruitment it is aspiration. But there is a deeper and more urgent reason why HBCU alumni chapters must show up here: elementary school is where the majority of Black boys are lost academically, and the window to intervene is narrow.

The data is unambiguous and devastating. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, only about 17 percent of Black fourth-grade students are reading at or above grade-level proficiency. For Black boys specifically, the numbers are worse. Only 13 percent of fourth-grade Black boys scored proficient in reading on the NAEP, compared to 40 percent of fourth-grade White boys. Research from the Annie E. Casey Foundation shows that children who are not reading proficiently by third grade are four times more likely to drop out of high school. And the cliff is steep: schools stop teaching children how to read after third grade and expect them to read to learn — for Black boys who missed early reading milestones, the system rarely slows down to help them catch up.

The academic struggle is compounded by the discipline crisis that runs parallel to it. Black boys represent just 8 percent of total K–12 enrollment but account for 15 percent of students receiving in-school suspensions and 18 percent of those receiving out-of-school suspensions. It starts before kindergarten: Black boys account for 9 percent of preschool enrollment but represent 23 percent of preschool children who received one or more out-of-school suspensions. Every day a Black boy spends outside the classroom is a day the reading gap widens. Black boys lost 132 days of instruction per 100 students enrolled due to out-of-school suspensions — a staggering accumulation of lost learning that trails these students for years. The research also shows that Black boys are markedly less likely to be subjected to exclusionary discipline when taught by Black teachers — a finding that speaks directly to the power of representation, and to what an HBCU alumnus standing in a classroom or community center can mean to a young Black boy who has rarely seen himself reflected in a position of educational authority.

This is why HBCU alumni chapters must be present in elementary schools — not with brochures, but with people. Reading programs, mentorship initiatives, and “college visit days” that introduce young children to the very concept of higher education are not extracurricular niceties; they are interventions. Seeing an HBCU alumnus or alumna in a professional role, wearing their school colors, and speaking with pride about their college experience plants a seed that can survive years of discouragement and doubt and provides a counter-narrative to a system that, by fourth grade, has already written too many Black boys off. Chapters should be cultivating relationships with school principals and PTA organizations to create recurring, sustained programming access. The presence has to be consistent, not occasional. A single visit does not change a trajectory. A relationship does.

Middle School (6th–8th Grade): By middle school, academic identity is forming and peer influence is at its peak. This is the moment to introduce students to HBCU culture, legacy, and opportunity in a way that makes it feel aspirational and cool. Alumni chapters should be running summer enrichment programs, college campus tours, and after-school STEM or arts programming tied to their institution’s academic strengths. Students who visit an HBCU campus at age 13 are far more likely to apply at 17.

High School (9th–12th Grade): This is the traditional recruitment window, but even here the storefront and mobile unit models change the game. Rather than waiting for students to find them at a fair, chapters are already embedded in these students’ communities. The work at this stage is conversion: helping students who are already HBCU-curious move through the application process, understand their financial aid options, and see themselves as belonging on campus. Chapters should have alumni assigned as informal advisors to high school college counselors — a presence that keeps HBCUs top of mind when counselors are guiding students toward school lists.

Adult Learners and Working Professionals: The traditional 18-to-22 pipeline is not the only one that matters. Millions of Black adults in American cities have some college credit but no degree. Alumni chapters that operate storefronts can become hubs for adult learner recruitment — connecting prospective students with their institution’s degree completion programs, online offerings, and evening or weekend formats. The FAFSA is available to adult learners. Institutional scholarships often target this population. Alumni chapters are uniquely positioned to be the trusted intermediary that convinces a 32-year-old with two kids and a job that finishing their degree is still possible.

Transfer Students: Community colleges in major metros serve enormous numbers of Black students who are academically capable of completing a four-year degree. Alumni chapters should have formal relationships with the counseling offices of every community college in their region, providing materials, hosting information sessions, and facilitating articulation agreement information that helps students understand how their credits will transfer to an HBCU.

Prospective Graduate Students: HBCUs are increasingly building out competitive graduate and professional programs. Alumni chapters can serve this market by hosting networking events that connect Black professionals with information about MBA, law, public health, and social work programs at their institution. The storefront model works exceptionally well here: an evening panel of HBCU-credentialed professionals discussing the value of their graduate degree, hosted at a community location, is both a recruitment event and an alumni engagement opportunity.

None of this is free, and alumni chapters should be honest with themselves about the resource requirements. A combined storefront and mobile operation with a full-time staff of five to six people, housed in leased or owned commercial space, represents a total annual operating budget — personnel, facilities, programming, and vehicle costs — likely in the range of $400,000 to $550,000 depending on market. That is a real community development organization, and it needs to be funded like one.

The good news is that the funding landscape is more favorable than many chapters realize — particularly for chapters willing to do the work of building a formal organizational structure, a board of directors, and a documented impact model.

Corporate partners, particularly those with HBCU engagement programs, represent another significant funding channel. Black-owned businesses in the communities where storefronts would operate should be natural co-investors: they benefit from a more educated local workforce and a more vibrant community anchor institution. Faith communities, which often have both facilities and congregational fundraising capacity, are underutilized partners for HBCU alumni chapters in nearly every city.

State and federal workforce development funding including Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act dollars can support adult learner programming and the Financial Aid Navigator role at storefront locations. Chapters with 501(c)(3) status or fiscal sponsorship arrangements can access this funding stream, as well as philanthropic grants from foundations focused on educational equity, Black wealth building, and community development. The mobile unit may also qualify for transportation equity and community access grants available through state education agencies and private foundations.

Here is the harder conversation that most alumni chapters are not having: grants run out, corporate partners change priorities, and institutional support is subject to the whims of university budget cycles. Any operational model built entirely on external funding is one budget cut away from collapse. The chapters that will sustain these operations for decades not just launch them with fanfare are the ones that build their own financial engine.

This means HBCU alumni chapters need to stop thinking of themselves purely as fundraising organizations and start thinking of themselves as investors. The distinction is critical. Fundraising asks others to fund your mission. Investing builds assets that fund your mission in perpetuity.

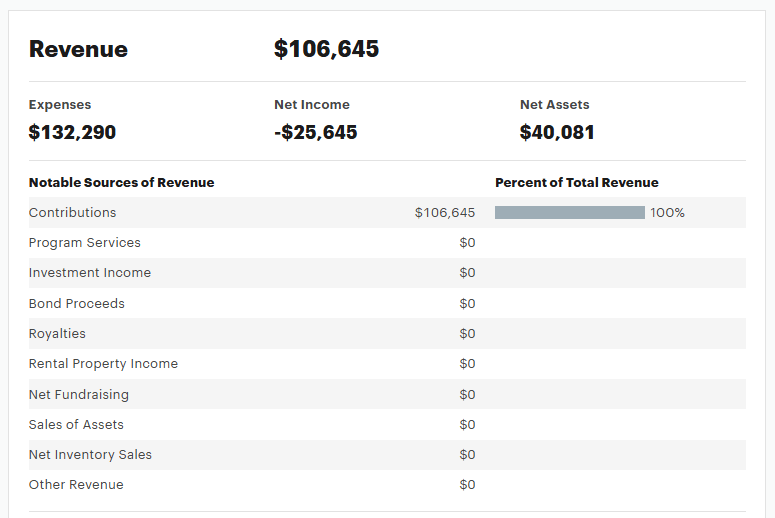

The first and most immediate step is the establishment of a formal chapter endowment. An endowment is not a reserve fund or a savings account, it is a permanently invested pool of capital whose principal is kept intact while the annual investment income is distributed for operations and programs. Most endowments are designed to keep the principal corpus intact so it can grow over time, while allowing the nonprofit to use the annual investment income for programs and operations. A chapter endowment seeded with $500,000 and professionally managed at a conservative annual return of 5 percent generates $25,000 per year in perpetuity — money that never has to be raised again. Scaled to $2 million, that is $100,000 annually without a single grant application. The endowment is built through major gifts from alumni, planned giving and bequest programs, proceeds from chapter events reinvested rather than consumed, and targeted endowment campaigns run every three to five years.

Beyond the endowment, chapters with the organizational maturity to do so should be seriously exploring the creation of a dedicated investment arm, a separate but affiliated entity structured as a 501(c)(3) foundation or a for-profit LLC depending on the chapter’s strategic goals, whose mandate is to build and manage a diversified portfolio of assets that generates income to fund chapter operations and community programs. Most endowments are set up as separate entities from the nonprofit they support, paying formal grants to the nonprofit, with a structure that requires a separate board of directors, officers, mission statement, and internal policies. This structure gives the investment arm its own governance, its own fiduciary standards, and its own identity while keeping the mission connection to the chapter clear and documented.

What does the portfolio of an HBCU alumni chapter investment arm look like in practice? Good old stocks and bonds to begin with to get the asset train rolling. Real estate comes next as a natural mission-aligned asset class as discussed. The storefront properties this article has already discussed are the starting point but the vision should not stop there. A chapter that owns its storefront, then acquires a second commercial property that it leases to a Black-owned business, then participates as a co-investor in a mixed-use affordable housing development in its target community, is building a real estate portfolio that generates rental income, appreciates in value, and reinforces the chapter’s identity as a community developer. Every property the chapter owns is a statement that Black institutional capital is permanent in this neighborhood.

Beyond real estate, chapter investment arms should be exploring mission-aligned equity investments in Black-owned businesses, HBCU-affiliated startups, and community development financial institutions. Alumni Ventures, a model pioneered in the broader higher education alumni space, has demonstrated that alumni funds can blend community focus with rigorous portfolio construction, leveraging deal flow to ensure quality and diversification. An HBCU alumni chapter investment fund that pools capital from members with minimum investment thresholds accessible to working professionals, not just the wealthy — democratizes wealth-building while directing capital toward enterprises that reflect the community’s values.

The chapters that will build these operations are the ones that stop thinking of themselves as social clubs with a community service component and start thinking of themselves as the community development and wealth-building arm of one of America’s most important institutional legacies. The storefront and the mobile unit are the mission. The endowment and the investment portfolio are what keep the mission alive when the grants run out and the corporate partners move on. Both are necessary. Neither is optional.

Every year that HBCU alumni chapters spend waiting at tables at college fairs is a year that students who could have found their way to a transformative HBCU education do not. The competition for Black students is fierce, well-funded, and increasingly present in the very communities where HBCUs have historically drawn their greatest strength.

The answer is not to compete on those terms. The answer is to go deeper, go earlier, and go to where the community lives. Storefronts and mobile units are not just recruitment tactics they are acts of institutional love and community investment. They say, loudly and visibly, that this HBCU is not waiting for students to find it. It is coming for them in the best possible way.

Alumni chapters have the people, the passion, and increasingly the resources to make this happen. What they need now is the will to think bigger than a folding table and a stack of brochures.

HBCU Money is the leading personal finance and business news platform focused on the HBCU community. To learn more about HBCU financial strategies, alumni engagement, and institutional development, visit hbcumoney.com.

Ideas that extend the physical infrastructure already proposed:

1. HBCU Alumni Chapter Media Studio — A small podcast/video production corner inside the storefront that creates original content: student success stories, “day in the life” campus videos, financial aid explainers, and alumni career spotlights. Content goes directly to YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram and keeps the chapter’s brand alive in the community 24/7 — long after the doors close. It serves as a recruitment tool that never sleeps and costs relatively little to set up.

2. Career and Internship Pipeline Desk — A formalized partnership structure between the storefront and local employers, specifically focused on creating internship and first-job pathways for HBCU students and graduates. The storefront becomes a local talent pipeline desk — something corporate partners can co-fund in exchange for access to HBCU talent. This also keeps alumni coming back after graduation and turns the center into a lifelong resource, not just an admissions office.

3. HBCU Health and Wellness Partnership — Several HBCU alumni alliances already do this. Given that health disparities in Black communities are severe, the storefront can host free health screenings, mental health workshops, and wellness programming co-sponsored by HBCU nursing and public health programs. This embeds the storefront even deeper in community trust and brings in foot traffic from people who may not initially be thinking about college at all — but who are now in the building.

Ideas that use the alumni chapter’s organizational capacity:

4. Returning Citizens / Reentry Pipeline — Formerly incarcerated individuals represent one of the most underserved and educationally motivated populations in Black communities. HBCUs that accept returning citizens and the Pell Grant restoration (reinstated in 2023) make this timely. The storefront is a natural hub for partnering with reentry organizations to connect this population with HBCU degree programs, adult learning pathways, and financial aid navigation.

5. HBCU Alumni Chapter Financial Cooperative — Rather than each chapter independently funding operations, HBCU chapters in a metro area or region could form a financial cooperative or CDFI (Community Development Financial Institution) to pool capital for real estate acquisition, bus purchases, and storefront buildouts. This turns the funding challenge from a per-chapter burden into a shared institutional strategy.

6. “HBCU House” Cultural Programming — Modeled loosely on cultural centers that exist in cities, the storefront runs regular cultural programming — film screenings, lectures, art exhibitions, Juneteenth and Black History Month events — that make it a destination even for community members with no immediate college interest. The goal is sustained foot traffic and community ownership of the space. The people who come for the film screening become the people who bring their kids back for tutoring.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ClaudeAI.