It’s tough for all farmers, but when you throw in discrimination and racism and unfair lending practices, it’s really hard for you to make it. – John Boyd, Jr., Founder of the National Black Farmers Association

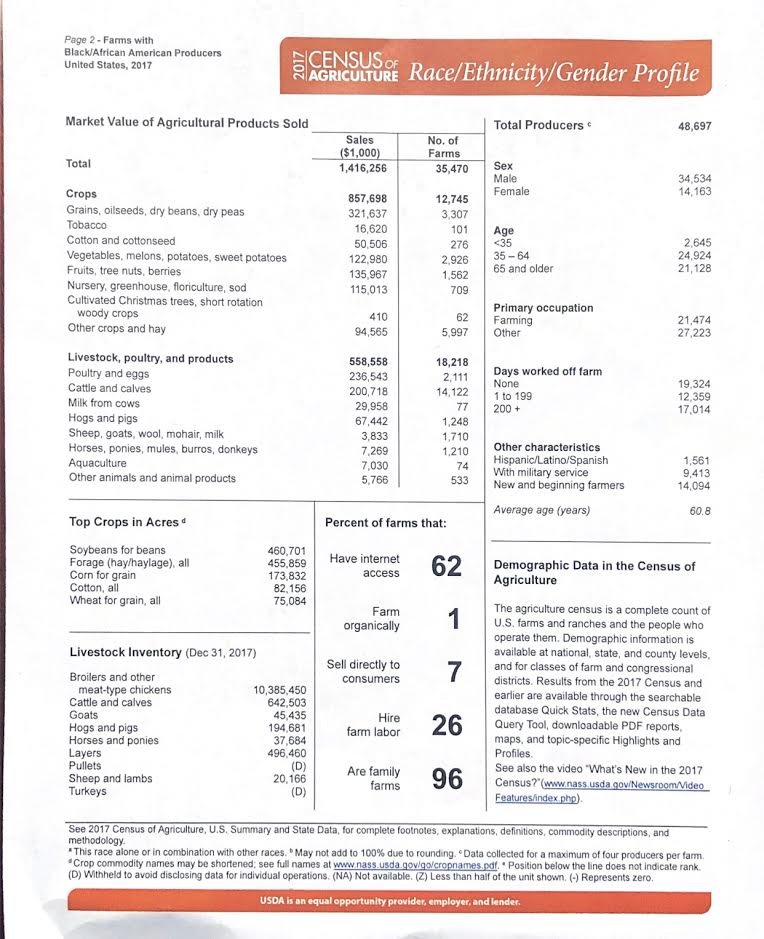

America’s oldest financial divide is agricultural. Once, the majority of African Americans lived and labored on land; now, less than 1.4% of the nation’s 3.4 million farmers are African American. The disappearance of Black farmers is not only a human story—it is a story of capital deprivation, institutional neglect, and the collapse of an ecosystem that once linked land, education, and community credit. To reverse this, imagine if each of the 19 land-grant institutions in the 1890 HBCU system committed $1 million from their endowments and alumni associations to create a unified private lending fund. This $19 million “1890 Fund” would not sit passively in treasuries or bond portfolios but circulate directly through African American banks and credit unions, financing African American farmers and food producers across the country. Such a fund would be modest in scale but revolutionary in concept, a self-directed act of institutional cooperation that reconnects three critical arteries of African American economic life: land-grant HBCUs, African American financial institutions, and Black agricultural producers.

The 1890 HBCUs, institutions such as Tuskegee University, Prairie View A&M, North Carolina A&T, and Florida A&M were established as part of the Second Morrill Act of 1890 to serve African Americans excluded from the original land-grant colleges. Their purpose was not abstract scholarship but applied science: to teach, research, and extend knowledge about agriculture, engineering, and the mechanical arts. Over time, many of these schools evolved into comprehensive universities. Yet the decline of Black farmers and the consolidation of farmland under non-Black ownership represent a direct erosion of the very population these universities were created to serve. Between 1910 and 2020, African American land ownership fell by roughly 90%, from an estimated 15–16 million acres to less than 2 million today. The structural dispossession through discriminatory lending, heirs’ property laws, and USDA bias has left African American farmers with less access to credit and fewer pathways to generational land retention. HBCUs were founded to be a shield against such vulnerability. The 1890 Fund would revive that founding spirit, transforming their agricultural programs and extension centers into engines of financial empowerment rather than merely research hubs dependent on federal grants.

Each 1890 HBCU would allocate $1 million from a combination of its endowment and alumni association reserves, with matching commitments encouraged through philanthropic donors or corporate partners. The pooled fund $19 million at launch would be professionally managed under a cooperative structure, similar to a community development financial institution or business development company. The fund would not make direct loans itself but would place its capital into African American-owned banks and credit unions identified in HBCU Money’s 2024 African American-Owned Bank Directory. Institutions such as OneUnited Bank, Industrial Bank, Citizens Trust Bank, and smaller but vital credit unions like FAMU Federal Credit Union or Hope Credit Union would serve as the lending conduits. In effect, the 1890 Fund would function as the “wholesale” capital pool of low-interest (but profitable), long-duration deposits or certificates placed with African American banks that, in turn, originate and service loans to qualified African American farmers, cooperatives, and agri-businesses. Loans would range from $25,000 micro-lines for new producers to $500,000 or more for established operations seeking equipment, irrigation, or land expansion. Priority would be given to farmers with relationships to HBCU agricultural programs such as those who have completed workshops, extension training, or student partnerships. Each bank or credit union participating would commit to transparent reporting, with loan performance and demographic data shared annually with the 1890 Foundation. The revolving structure of repayments would ensure that as farmers succeed, their payments replenish the pool for new borrowers creating a regenerative loop of institutional and community wealth.

Routing the fund through African American financial institutions is not symbolic it is structural. Historically, Black farmers were denied access to credit through traditional banks and faced redlining by federal programs. Even today, USDA lending disproportionately benefits white farmers. African American banks and credit unions remain among the few institutions with both the cultural understanding and community trust necessary to underwrite these borrowers responsibly. Moreover, these banks themselves are chronically undercapitalized. With combined assets of roughly $7.5 billion across the sector, African American banks represent barely 0.001% of total U.S. banking assets, insufficient to exert meaningful influence in national credit markets. By placing deposits into these banks, HBCUs would strengthen their liquidity ratios, reduce dependence on volatile retail deposits, and expand lending capacity far beyond the fund’s nominal amount through fractional reserve leverage. In short, every dollar committed by an HBCU could translate into $7–$10 in agricultural lending capacity once multiplied through the banking system.

HBCU alumni associations hold untapped potential as financial intermediaries. While endowments must operate under fiduciary and investment constraints, alumni associations often have greater flexibility. They can act as private limited partners in the 1890 Fund, contributing capital from dues, life membership funds, or targeted campaigns such as “Adopt-a-Farmer.” Imagine an alumni chapter of Florida A&M underwriting 10 acres of hydroponic greens for a local farmer who agrees to hire FAMU agriculture graduates. Or Prairie View alumni pooling funds to purchase cold-chain trucks for dairy producers across Texas. These actions extend the HBCU brand into the real economy transforming loyalty into tangible economic development. Each alumni association could also create its own micro-fund linked to the central 1890 Fund, mirroring the “chapter endowment” concept used by major universities. This networked structure would democratize investment and bring the broader African American middle class into the process of agricultural renaissance.

Lending alone does not sustain farmers; ecosystems do. The 1890 Fund would operate most effectively if it integrated with the broader HBCU agricultural and business infrastructure. HBCU agricultural economists could conduct continuous impact analysis tracking how capital access affects yields, profitability, and land retention. Their findings would strengthen advocacy for increased African American private capital. Extension programs could pair loan recipients with agronomists and soil scientists to ensure that capital is used productively and sustainably. HBCU-affiliated food labs, hospitality programs, and dining services could prioritize procurement from funded farmers, creating closed-loop demand. Business schools could develop crop insurance products and risk models tailored to small producers, mitigating the vulnerability that has historically devastated African American farms. Student internships in finance, agriculture, and data science could be embedded in the fund’s operations training the next generation of agricultural financiers and analysts. This approach transforms the 1890 Fund from a mere loan pool into a comprehensive agricultural development platform.

The greatest strength of the 1890 Fund lies in its multiplier effect. Consider: $19 million revolving annually at a conservative 6% loan rate generates roughly $1.1 million in annual interest income—income that can be reinvested or partially distributed back to participating universities to grow the fund. If repayments are recycled annually, the fund could underwrite over $100 million in cumulative loans within its first decade. The macroeconomic ripple is job creation, land retention, and input purchases that would expand rural GDP in African American counties and increase deposit growth for the participating banks. Contrast this with the status quo: endowment funds largely held in Wall Street instruments that yield moderate returns but generate no localized impact. By re-directing even a fraction of assets into mission-aligned community lending, HBCUs align their investments with their historic purpose of educating and empowering the descendants of those who built the land.

The global contest for food security is intensifying. Nations that control food production, water, and soil fertility will control the future. For African America, regaining agricultural capacity is not nostalgic it is strategic. Every acre restored to productive use by African American farmers increases food sovereignty and reduces dependence on foreign or corporate supply chains. If HBCUs act collectively through the 1890 Fund, they position themselves as key players in regional and national food policy. They could partner with African universities for climate-resilient crop research, link with Caribbean agricultural cooperatives for trade, and develop transatlantic agribusiness ventures under the banner of Black institutional power. Such cooperation would redefine “land-grant” for the 21st century not as a relic of American expansion but as a global model of Pan-African capital deployment.

The road to building the 1890 Fund will not be smoothed by political cooperation. The federal and state governments that oversee the 1890 land-grant system are, in many cases, openly hostile toward African American advancement. Most of the 1890 HBCUs operate in states where racial resentment, austerity politics, and legislative interference remain the norm. These are states that have withheld or delayed millions in matching funds, imposed discriminatory audits, and used political appointments to keep HBCUs subordinate to their predominantly white peers. Under such conditions, the 1890 Fund is not merely an investment vehicle it is a form of institutional defense. Federal and state policy cannot be relied upon to sustain African American agriculture or financial independence. The only realistic path forward is one where HBCUs, alumni associations, and African American banks coordinate their own internal economy of capital, shielded from political manipulation.

This is where the 1890 Foundation becomes indispensable. Established to support the collective mission of the 1890 universities, the Foundation already exists as a neutral, centralized, and professionally managed entity capable of administering joint initiatives on behalf of all 19 institutions. Tasking it with managing the 1890 Fund would provide immediate credibility, legal infrastructure, and continuity. The Foundation could structure the fund as a private, revolving loan pool, capitalized through contributions from university endowments, alumni associations, and strategic partners, while remaining beyond the reach of hostile state legislatures. Governance through the 1890 Foundation would also protect participating universities from political retaliation. Rather than each HBCU appearing to act independently potentially inviting scrutiny from governors or state boards the fund’s activities could be coordinated under the Foundation’s national charter. This collective structure would allow for scale, professional risk management, and a unified investment policy aligned with the long-term interests of African American farmers and institutions.

Nevertheless, challenges remain. Some university boards, especially those with state-appointed trustees, may hesitate to commit endowment dollars to what they perceive as politically sensitive or unconventional investments. The uneven size of endowments ranging from under $50 million at smaller 1890s to more than $200 million at the largest could create tensions over proportional contributions. And while the 1890 Foundation provides an ideal governance structure, it would still need to secure regulatory clarity and investment expertise to manage a multi-million-dollar lending operation through external financial institutions. These risks, however, are outweighed by the opportunity to build economic sovereignty in an era of state hostility. The very conditions meant to weaken HBCUs like political obstruction, financial starvation, and bureaucratic oversight can become the catalysts for collective independence. If the 1890 Fund channels its capital through African American banks and credit unions, it strengthens two institutional pillars simultaneously: HBCUs regain control over how their endowments circulate, and Black-owned financial institutions gain the liquidity and leverage they need to expand.

The political hostility surrounding 1890 HBCUs should not be seen as a deterrent, but as confirmation of why this fund must exist. It demonstrates that African American progress, even in the 21st century, cannot depend on state benevolence. By empowering the 1890 Foundation to manage a private, self-sustaining fund, HBCUs would be acting in the same spirit of independence that defined their creation in 1890 when the federal government forced states to either open their existing land-grant colleges to Black students or create new ones for them. The 1890 Fund would be the modern continuation of that act of defiance transforming exclusion into enterprise. Through the 1890 Foundation’s leadership, African American endowments, farmers, and banks could finally operate in unison, beyond the grasp of state control. In doing so, they would build not just a lending mechanism, but a shield—a financial structure capable of outlasting political hostility and securing the long-term survival of Black agricultural and institutional power.

If the 1890 Fund fulfills its purpose, its long-term success should evolve into something even greater, a joint venture between the 1890 Foundation, African American banks, and African American credit unions that establishes a new national financial institution: one modeled on the Farm Credit System but existing independently from it to preserve full financial sovereignty. The Farm Credit System is a government-sponsored network of cooperative lenders that provides over $400 billion in loans and financial services to farmers, ranchers, and agricultural businesses across the United States. Its reach is vast and influential, covering roughly 40% of all agricultural debt in the country. Yet African American farmers have historically been excluded from its benefits. The FCS, like much of American agricultural policy, was built in an era when Black ownership was being systematically dismantled. It became a backbone for white rural wealth while African American farmers were left to navigate a labyrinth of local banks, discriminatory USDA programs, and predatory lending.

A successful 1890 Fund would prove that African American institutions: universities, banks, and credit unions can design a credit network capable of rivaling the FCS’s effectiveness, without its dependencies or racial exclusions. Over time, this collaboration could be formalized into a joint enterprise: the African American Agricultural Credit Alliance: a cooperative, member-driven, nationwide system built to finance not just farms but the entire food and fiber value chain. Like the FCS, it could be composed of multiple regional lending cooperatives, each capitalized by a blend of HBCU endowment investments, bank deposits, and credit union member capital. At its center would sit a national coordinating body responsible for liquidity management, risk pooling, and bond issuance. But unlike the FCS, this alliance would be entirely private and its governance drawn from the 1890 Foundation, the African American Credit Union Coalition, and the National Black Farmers Association. The goal would not be to replicate the FCS’s structure exactly but to rival its scale, providing affordable credit, insurance, equipment financing, and agri-business investment under the umbrella of Black-owned control.

Refusing to integrate into the existing Farm Credit System is not a rejection of efficiency it is a declaration of sovereignty. The FCS, though cooperative in name, ultimately answers to federal regulators, congressional committees, and a system of oversight that has never prioritized Black agricultural survival. Independence ensures that capital allocation decisions remain rooted in African American priorities—restoring land, building ownership, and sustaining communities rather than maximizing short-term returns. Financial sovereignty also allows for creative lending models that the FCS cannot adopt under federal restrictions, such as cooperative land trusts, heirs’ property buyouts, carbon-credit-backed collateral, or blockchain-based agricultural exchanges.

The evolution from the 1890 Fund to a fully realized agricultural credit system would expand capital from millions into billions. Once the fund demonstrates consistent performance, its track record could attract institutional investors like African American foundations, pension funds, and even sovereign funds from the African diaspora seeking mission-aligned, asset-backed investments. Through securitization and bond issuance, the alliance could channel long-term capital into rural Black communities, funding everything from precision agriculture and agroforestry to food processing and logistics. This would make agriculture once again an attractive sector for young entrepreneurs and HBCU graduates. Over time, the 1890 Fund could thus mature into an ecosystem capable of reindustrializing Black rural America through ownership and control of capital.

The creation of such a system would carry global implications. It could link with agricultural cooperatives in Africa and the Caribbean, forming a transatlantic agricultural finance corridor and positioning African American institutions as both lenders and investors in global food systems. The founding of the 1890 Fund, therefore, would not be an endpoint but the beginning of a long journey toward financial nationhood. The eventual establishment of an independent agricultural credit alliance would mark the institutionalization of economic sovereignty—a transformation from temporary coordination to permanent capacity.

The 1890 Fund embodies the principle that power comes from ownership, not participation. For too long, African American institutions have waited for external validation or federal rescue. The tools for rebuilding agricultural sovereignty already exist: universities with land and research infrastructure, banks with local lending channels, and farmers with generational knowledge. When linked together, these elements form a complete ecosystem capable of restoring both land and leverage. The $1 million commitment from each 1890 HBCU would not be a gift it would be a strategic investment in self-determination. If executed, within a generation the 1890 Fund could help reclaim millions of acres, incubate thousands of Black-owned farms, and expand the asset base of African American financial institutions. It would also serve as a model for other sectors like manufacturing, housing, and technology demonstrating how collective capital deployment transforms a marginalized community into a nation within a nation.

As Dr. Booker T. Washington once observed, “No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem.” The modern corollary is that no people can be free until they can finance their own fields. The 1890 Fund is not only a mechanism for loans it is a blueprint for liberation through institutional coordination. Its success could lay the groundwork for a sovereign financial architecture that, like the land it seeks to reclaim, will belong entirely to the people who cultivate it.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.