“I know I got it made while the masses of black people are catchin’ hell, but as long as they ain’t free, I ain’t free.” – Muhammad Ali

The recent news that Intel will discontinue its $1 million annual funding of North Carolina Central University’s (NCCU) Technology Law and Policy Center is more than just a line item in the university’s budget. It is a sharp reminder of how precarious institutional development becomes when African American colleges and universities rely on the European American corporate cycle of generosity and withdrawal. Where is African American corporate philanthropy is a pertinent question, but an article for another day.

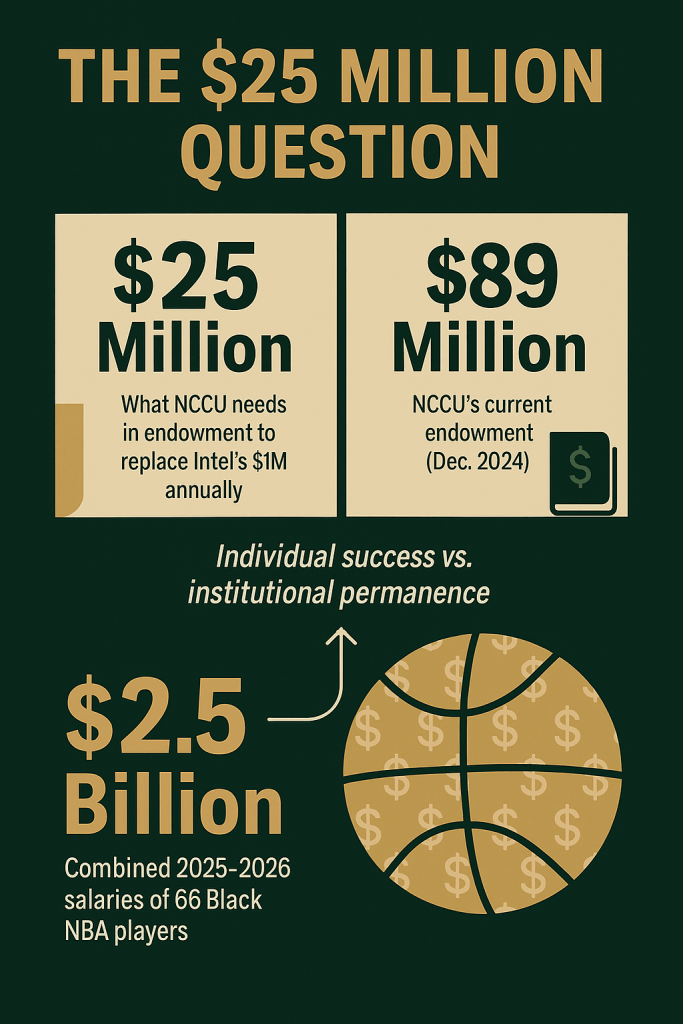

Intel’s departure leaves a gap that must now be filled through other means. But the mathematics of filling it points to a broader truth: without substantial, permanent endowments, HBCUs will remain vulnerable to the political and financial whims of European American corporations. To replace $1 million in annual program funding, NCCU would need to raise between $20 million and $25 million in endowment principal assuming a 4–5% annual spending rate, the standard in higher education finance.

The fact that an entire academic pipeline, designed to produce future African American lawyers and policymakers, can be destabilized by a single corporate decision underscores the fragility of HBCU institutional power. And it raises a haunting contrast: while 66 African American NBA players will together earn $2.5 billion in salaries this upcoming season, not a single African American university controls an endowment robust enough to insulate it from the kind of disruption Intel’s withdrawal has now caused.

The mechanics are straightforward. Endowments work by pooling donated capital, investing it, and spending a sustainable portion of annual returns—usually 4–5%. To replace Intel’s $1 million annual gift, NCCU must therefore build an endowment of $20–25 million. This is not extraordinary by university standards. At most predominantly white institutions (PWIs), a $25 million endowment is considered modest. At Harvard, Yale, or Stanford, it would not even make the footnotes. Yet for NCCU, an institution with an endowment of $89 million as of December 2024, the sudden need for another $20–25 million underscores the gap between HBCUs and their white peers.

The underlying truth is that corporate funding is inherently unstable. It ebbs and flows with market cycles, political administrations, and corporate priorities. Endowments, however, endure across generations. The very act of raising such capital is itself an exercise in institutional power: it demonstrates to the world that the university and its community can stand on their own financial feet.

Intel did not single out NCCU maliciously. The company is undergoing a profound transformation, not least because the U.S. government has become its largest shareholder after a multi-billion-dollar deal with the Trump administration. Like other firms facing political scrutiny, Intel is quietly shedding high-profile DEI commitments. For NCCU, however, the effect is real. The Technology Law and Policy Center was designed to provide African American law students with training in emerging technology and policy—a space historically closed to Black lawyers. It also featured internships at Intel, summer placements, and the now-defunct “Intel Rule,” which required outside law firms to staff diverse teams if they wanted Intel’s business. Now, without a replacement funding mechanism, the Center risks contraction. Students will still enroll. Faculty will still teach. But the acceleration that Intel’s money provided—the ability to recruit nationally, to build cutting-edge programming, to give students exposure to high-tech legal practice—will slow.

Enter the paradox of the NBA’s 66 Black players earning $25 million or more in the upcoming season. Collectively, those 66 players will earn $2.5 billion in salary during the 2025–2026 season. Each of these players individually makes at least what NCCU would need to permanently replace Intel’s $1 million annual commitment through endowment. The collective sum is staggering: $2.5 billion in one season—enough to seed $25 million endowments at 100 HBCUs.

It is not about individual responsibility. No one player can be expected to save an institution. But collectively, the paradox points to the imbalance between African American individual wealth and African American institutional poverty. Even if just 10% of that wealth—$250 million—were organized and directed into HBCU endowments, the result could replace Intel’s contribution not only at NCCU but across multiple campuses. Yet there is no mechanism, no institutional strategy, no coordinated pipeline that directs such flows into African American universities. This is not new. For decades, African American excellence has been harvested at the level of the individual, while African American institutions have remained underfunded. The NBA is simply the latest, most visible example.

The Intel withdrawal reminds us of a hard truth: reliance on outside benevolence is not a strategy for power. It is, at best, a strategy for survival. Corporate giving is always the first budget item to shrink when recession looms or political winds shift. For HBCUs, this means programs rise and fall on decisions made in Silicon Valley or Wall Street boardrooms—far removed from Durham, Tallahassee, Baton Rouge, or Montgomery. The vulnerability is compounded when African American communities assume that the generosity of corporations will substitute for building our own endowments. The danger is not simply financial but cultural: it conditions us to believe that power comes from outside, not from within.

Intel’s $1 million a year was not charity—it was investment. It bought Intel goodwill, a trained pipeline of diverse lawyers, and reputational capital in the DEI era. Now that DEI is politically unpopular, the investment is deemed expendable. This is why endowments matter. They are not subject to the quarterly report or the election cycle. They anchor institutions in the long term.

Let’s be clear about the scale of the challenge. The combined endowments of all HBCUs hover around $4 billion, compared to more than $800 billion at PWIs. Harvard alone has an endowment of nearly $52 billion. NCCU’s endowment stands at $89 million. To raise an additional $20–25 million to replace Intel’s support would represent a 22–28% increase in its current endowment base. Such a leap is achievable—but it requires strategy. It means cultivating alumni giving systematically. It means leveraging African American wealth beyond alumni, drawing in professional athletes, entertainers, and entrepreneurs. It means creating vehicles—donor-advised funds, pooled endowments, institutional investment cooperatives—that make giving both efficient and impactful. Most of all, it means shifting mindset. We must stop thinking of endowments as luxuries reserved for Ivy League institutions. They are necessities. They are the only way to secure institutional independence.

The Intel decision can serve as a turning point, if we are willing to see it clearly. Corporations are not institutional guardians. They may play a role, but they will not underwrite our survival. Their goals are their own. When interests diverge, as they now have, funding vanishes. Individual wealth must be institutionalized. The contrast between NBA salaries and HBCU endowment poverty is not about shaming athletes. It is about building structures that make institutional giving the default, not the exception. Endowments are the only safety net. No government program, no corporate sponsorship, no philanthropic fad can substitute. Only endowments give institutions perpetual capacity to fund themselves.

What would it take, concretely, for NCCU to raise the $25 million needed? A handful of major gifts in the $2–5 million range from alumni, athletes, or African American business leaders could jump-start the campaign. NBA, NFL, and WNBA players could be recruited to create a pooled fund. Instead of individual gifts, imagine a collective “Athletes for HBCU Endowments” initiative. African American foundations and community funds could direct grants toward seed capital, matched by alumni. If every NCCU law graduate gave $1,000 a year for ten years, the cumulative effect would approach the tens of millions. NCCU could also partner with African American-owned banks and investment firms to maximize returns and circulate dollars within the community. The strategy would not only replace Intel but set a precedent: when outside money leaves, we do not shrink. We build.

The broader question is not whether NCCU will survive the loss of Intel’s support. It will. The real question is whether African American institutions will continue to live in the shadow of dependency—or whether we will use moments like this to chart a new course. The paradox of $2.5 billion in NBA salaries versus the need for a $25 million endowment is not just a rhetorical flourish. It is a mirror held up to African America. It asks whether we will continue to celebrate individual wealth while neglecting collective survival.

Every dollar of Intel’s withdrawal can be replaced. But only if African American wealth is organized. Only if alumni, athletes, and entrepreneurs see endowments not as gifts but as obligations. Only if we remember that the true measure of power is not what any one of us earns, but what we can build together.

Intel has reminded us of an uncomfortable truth: corporate giving is temporary. Endowments are permanent. To replace $1 million a year, NCCU needs $25 million in endowment. That number is not insurmountable. It is the equivalent of one NBA salary in a single season. There are 66 African American players earning at least that much this year alone, with combined salaries of $2.5 billion. The juxtaposition is stark: individuals flourish while institutions starve. The future of HBCUs—and the broader African American ecosystem—depends on closing that gap. Until African America learns to institutionalize its wealth, every Intel withdrawal will feel like a crisis. But the day we build our endowments, such exits will be footnotes. And our institutions will finally stand on the firm ground they have always deserved.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.