I have discovered few learning disabled students in my three decades of teaching. I have, however, discovered many, many victims of teaching inabilities. – Marva Collins

When the Eight Schools Association, comprising Phillips Exeter, Phillips Andover, Choate Rosemary Hall, and other elite boarding schools, sends delegations to the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair or MATHCOUNTS Championships, they arrive with institutional power behind them. Generations of alumni networks, endowments in the hundreds of millions, dedicated competition coaches, and a culture that expects excellence. These schools don’t just prepare students for competitions; they’ve built entire ecosystems that produce winners systematically.

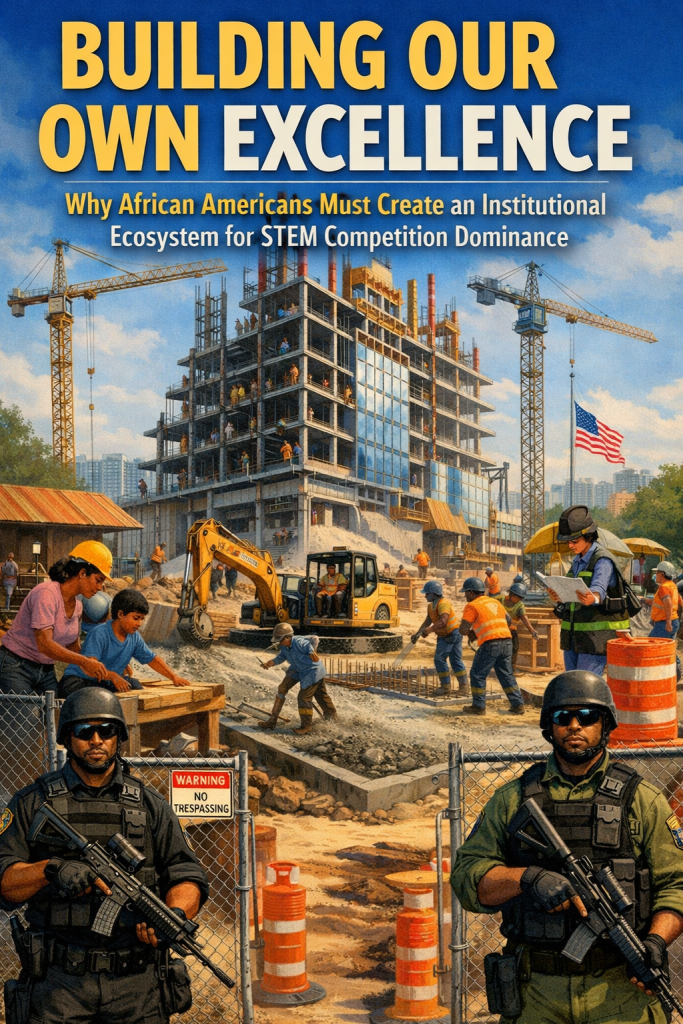

The African American community needs the same—not to gain access to their institutions, but to build our own parallel ecosystem of excellence. This isn’t about integration into existing structures; it’s about developing Black-controlled educational institutions that create seamless pipelines from kindergarten through college, from HBCU undergraduate research to Black-owned businesses and laboratories. It’s about institutional sovereignty and generational wealth-building through education.

The infrastructure already exists in fragments: four remaining historic Black boarding schools fighting for survival, HBCU laboratory schools serving thousands of students on HBCU campuses, scattered private Black schools across the nation, and 101 HBCUs waiting to receive the next generation of Black scholars. What’s missing is the connective tissue—the strategic vision to link these institutions into a powerhouse network that rivals anything the Eight Schools Association offers, while recognizing that most Black families need day school options, not just boarding programs.

African American students’ underrepresentation in elite STEM competitions—Science Olympiad, USA Biology Olympiad, American Computer Science League, Conrad Challenge isn’t a talent problem. It’s an institutional problem. When majority-Black schools face closure rates nearly double that of other schools nationwide, according to Stanford research, competition programming becomes an afterthought, if it exists at all. Meanwhile, prestigious institutions treat competition success as institutional mandate. They hire Ph.D.-level coaches, fund unlimited travel to regional and national contests, maintain state-of-the-art laboratories and makerspaces, and celebrate academic victories with the same fervor as athletic championships. Most importantly, they’ve built alumni networks spanning decades that provide mentorship, internships, and career pathways for graduates.

The Eight Schools Association demonstrates what institutional coordination achieves. These schools share best practices, collaborate on programming, and maintain standards of excellence that elevate all members. Their graduates don’t just attend elite colleges; they create companies, endow professorships, and return resources to strengthen the institutions that launched them. African Americans need this same institutional architecture but built for us, by us, serving our community’s interests and priorities.

While boarding schools capture attention with their prestige and immersive environments, the reality is that most Black families want and need high-quality day schools. Boarding schools serve grades 9-12 and require families to send children away, a proposition that doesn’t align with many Black family structures, cultural values, or financial realities. The future of Black educational excellence must therefore be built on a foundation of elite private day schools serving Pre-K through 12, supplemented by strategic boarding school options for families who choose that path.

Only four historic African American boarding schools remain from the over 100 that once existed: The Piney Woods School in Mississippi, Laurinburg Institute in North Carolina, Pine Forge Academy in Pennsylvania, and Redemption Christian Academy in upstate New York. These institutions represent more than educational options—they embody Black self-determination in education. The decline from over 100 to just four is a catastrophic loss of Black educational infrastructure that demands urgent reversal. But the primary focus must be on establishing a network of at least fifty elite Black private day schools across the country within the next decade, complemented by fifteen boarding schools for families seeking that option. Together, these institutions would create a comprehensive ecosystem serving Pre-K through grade 12, explicitly designed to rival the Eight Schools Association and other elite networks in resources, reputation, and results.

The day school model solves multiple practical challenges. Families maintain daily contact with their children while accessing elite education. Schools can serve Pre-K through 12, creating 14-year pipelines instead of just four years. Geographic coverage can be broader, with schools in major metropolitan areas where Black families are concentrated. And costs per student are lower than boarding, making sustainability more achievable.

Each elite Black private day school in the network would be designed as a competition powerhouse from the ground up. This means recruiting PhD-level faculty and competition coaches—the same caliber of talent that elite institutions employ. Science programs need teachers with doctoral degrees who’ve conducted research and understand how to prepare students for Olympiad-level competition. Mathematics departments require faculty who’ve published in their fields and can coach students to MATHCOUNTS and AMC excellence. Computer science programs need instructors with both academic credentials and industry experience who can lead programming teams to national prominence.

The Eight Schools Association succeeds because they pay top dollar for elite talent. Black private schools must do the same, offering competitive salaries that attract the best minds to teach our students. This isn’t optional it’s the price of competing at the highest levels. A well-meaning teacher with a bachelor’s degree cannot compete against PhD coaches at elite institutions. We must match their investment in human capital.

Beyond faculty, these schools require world-class infrastructure. State-of-the-art science laboratories where students can conduct genuine research. Extensive libraries with digital and physical resources rivaling small colleges. Advanced makerspaces with 3D printers, laser cutters, and robotics equipment. Computer labs with the latest technology. Athletic facilities that support both physical education and competitive sports. These facilities cannot be afterthoughts they must be built from the beginning to match or exceed what elite independent schools offer.

These schools must be strategically distributed across the country, not hostage to HBCU locations. Major metropolitan areas with significant Black populations need multiple options. Atlanta should have at least three elite Black private day schools. The DMV area (D.C., Maryland, Virginia) needs at least four. Houston, Dallas, Chicago, Detroit, New Orleans, Memphis, Charlotte—each requires multiple institutions to serve their communities adequately. But the network must also extend to underserved regions. New Mexico, Maine, the Pacific Northwest, Montana—areas with smaller but growing Black populations deserve options beyond traditional centers. These schools serve dual purposes: providing excellent education to local Black families and attracting families willing to relocate for access to elite Black institutions.

Boarding schools, given their residential nature and focus on high school, can be even more geographically flexible. A boarding school in rural Vermont or coastal Oregon can draw students nationally, serving families across the country who choose that educational model for grades 9-12.

Each school—whether day or boarding—should partner with one or more HBCUs through strategic regional arrangements. For instance, Atlanta’s day schools could partner with Spelman, Morehouse, Clark Atlanta, and Morris Brown. A boarding school in Texas could be triangulated between Prairie View A&M, Texas Southern, Grambling, and Southern University, with all four institutions sharing governance and pipeline responsibilities.

This distributed partnership model offers several advantages. HBCU faculty from multiple institutions would serve on academic boards, bringing diverse expertise while ensuring curriculum rigor and alignment with college expectations. Students would have guaranteed pathways to any partner HBCU, expanding their options beyond a single institution. College students from partner HBCUs could supplement as residential advisors and tutors, gaining education experience while strengthening connections between institutions.

However, to truly compete with the Eight Schools Association, these boarding schools must recruit PhD-level faculty and coaches—the same caliber of talent that elite institutions employ. Science competition teams need coaches with doctoral degrees in their fields, not just enthusiasm. Mathematics programs require faculty who’ve published research and understand competition mathematics at the highest levels. Computer science teams need instructors with industry and academic credentials. The Eight Schools Association succeeds because they pay top dollar for elite talent; Black boarding schools must do the same, offering competitive salaries that attract the best minds to teach and coach our students.

These K-12 institutions cannot be dependent on HBCU facilities or resources. To truly compete with elite independent schools, they must build and maintain their own infrastructure and secure their own endowments. Each elite day school should target minimum endowments of $50-100 million. Each boarding school should aim for $100-200 million. These endowments ensure financial sustainability, enable need-blind admissions, support competitive faculty salaries, and provide unlimited resources for student opportunities. HBCU partnerships provide crucial academic connections and pipeline benefits, but the K-12 institutions themselves must stand as independently powerful schools capable of competing with the best in America.

For this ecosystem to succeed, competition excellence cannot be an extracurricular afterthought—it must be embedded in institutional DNA from day one. Every school in the network should mandate that students participate in at least one major STEM competition annually. This normalization is critical. When competition participation becomes expected rather than exceptional, students prepare differently, families support differently, and results follow.

Consider what this looks like in practice at an elite Black day school serving Pre-K through 12. Elementary students (grades 3-5) participate in regional Science Olympiad divisions, Math Kangaroo, and Lego robotics competitions. Middle schoolers (grades 6-8) compete in MATHCOUNTS, Science Bowl, National History Day, and American Computer Science League. High schoolers (grades 9-12) engage in USA Biology Olympiad, Chemistry Olympiad, Physics Olympiad, Congressional Debate, Model UN, and Intel Science Fair. Every student finds competitions aligned with their interests and abilities. The school’s culture celebrates competition success publicly and prominently—trophies in display cases, assemblies honoring winners, media coverage of achievements. Academic competition excellence becomes as central to institutional identity as athletics at traditional schools.

The network should also establish its own internal competitions. An annual Black Excellence Science Olympiad. A Black School Network MATHCOUNTS Championship. Computer science competitions exclusively for students in the pipeline. These internal competitions provide practice grounds while building institutional identity and healthy rivalry that elevates performance across all schools.

HBCU laboratory schools—at institutions like Alabama State University (which pioneered the model in 1920), Southern University, Florida A&M, Howard University, and North Carolina A&T—serve crucial roles in this ecosystem. Virginia’s recent incorporation of laboratory schools at Virginia Union University and Virginia State University shows continued commitment to the model. These schools can serve as proof-of-concept institutions, demonstrating what’s possible when Black schools receive adequate resources and maintain rigorous competition programming. Their success provides templates for independent day schools to replicate. A laboratory school that sends students to national Science Olympiad championships proves the model works; independent schools can study their methods and adapt them.

Laboratory schools should also function as regional hubs, establishing partnerships with at least five majority-Black schools in their areas. They share competition resources, coaching expertise, and best practices, elevating the entire region’s performance while identifying top talent. Southern University Lab School partners with New Orleans-area Black schools. FAMU’s developmental research school does the same in Florida. Howard Middle School anchors D.C.-area networks. This hub-and-spoke model accelerates ecosystem development beyond the schools the network directly controls. Within five years, hundreds of majority-Black schools have competition programming that didn’t exist before, creating a rising tide that lifts all boats.

None of this happens without resources, and HBCU alumni must lead the investment. Every HBCU has thousands of successful graduates—doctors, engineers, lawyers, business owners—who could fund this institutional development. The goal isn’t charity but investment in infrastructure that strengthens the entire Black community. Alumni funding priorities should include capitalizing day school construction in major metropolitan areas nationwide, establishing minimum $50-100 million endowments for each day school to ensure sustainability, endowing boarding school scholarships so talented students can attend regardless of family income, funding PhD-level faculty recruitment with competitive salary packages, constructing world-class facilities—laboratories, libraries, makerspaces, athletic complexes—that rival elite independent schools, and creating venture capital funds that support businesses founded by network graduates.

The Eight Schools Association’s power derives largely from alumni commitment. Exeter’s endowment exceeds $1.5 billion. Andover’s tops $1.3 billion. These resources enable need-blind admission, world-class faculty recruitment, and unlimited opportunities for students. Black schools need similar commitments scaled appropriately. What if Spelman and Morehouse alumni collectively committed $200 million to establish three elite Black day schools in Atlanta? What if Howard University graduates funded two D.C.-area day schools with combined endowments of $150 million? These numbers are achievable when alumni understand they’re not donating to charity but investing in institutional power that will serve generations.

Regional alumni coalitions should form specifically to capitalize schools in their areas. The Texas HBCU Alumni Coalition funds schools in Houston and Dallas. The Midwest HBCU Coalition establishes schools in Chicago and Detroit. The Southeast Coalition covers Atlanta, Charlotte, and Memphis. This regional approach creates ownership and ensures schools reflect their communities’ needs.

While building new elite institutions is essential, the network must also elevate existing Black private schools and support majority-Black public schools in developing competition cultures. Not every Black school can or should become a boarding institution, but every Black school can raise its educational rigor and competition participation. The network should establish a tiered certification system. Tier One schools meet the highest standards—PhD faculty, comprehensive competition programming, world-class facilities, and proven track records of sending students to top competitions and HBCUs as elite scholars. Tier Two schools are developing toward these standards with network support. Tier Three schools are beginning the journey, receiving mentorship and resources from established institutions.

This certification creates aspirational goals while providing roadmaps for schools at different development stages. A small Black private school in Birmingham might begin as Tier Three, receiving coaching expertise and competition funding from the network. Within five years, they achieve Tier Two status. Within a decade, they’re Tier One, competing nationally and serving as a regional hub themselves. The network succeeds not only by building new schools but by elevating all Black schools toward excellence. Every student in a majority-Black school—whether public, private, or laboratory school—should have access to competition programming, rigorous academics, and pathways to HBCUs and beyond.

The ultimate goal transcends competition trophies and college admissions. This ecosystem should produce a generation of Black scientists, engineers, and entrepreneurs who build institutions, create wealth, and invest back into the network that developed them. A student who attends an elite Black day school from Pre-K through 12, earns a degree from an HBCU, and then receives seed funding from the network’s venture capital arm to launch a tech company—that’s the full pipeline. Ten years later, that founder endows scholarships at their alma maters and hires exclusively from the network. This is how generational wealth builds and how communities transform economically.

The competition focus matters because STEM competitions lead to STEM careers, which offer the highest salaries and most secure employment in the American economy. But the jobs aren’t enough. The network must produce business owners, not just employees. Laboratory directors, not just lab technicians. University presidents, not just professors. The institutional ecosystem must aim for complete economic sovereignty. Black-owned research laboratories should hire preferentially from network schools. Black engineering firms should recruit from HBCU programs fed by network pipelines. Black investment funds should capitalize businesses founded by network graduates. This closed-loop system ensures wealth circulates within the Black community, building generational prosperity.

The vision is clear, but visions don’t implement themselves. This ecosystem requires institutional leadership with the authority, resources, and commitment to coordinate across decades. The answer must be a new entity—a Black Educational Excellence Consortium governed by a coalition of HBCU presidents, major HBCU alumni association leaders, Black philanthropists, and representatives from the four remaining boarding schools. This consortium would function similarly to how the Eight Schools Association coordinates among its members, but with broader scope covering day schools, boarding schools, and laboratory schools.

The consortium’s core responsibilities would include establishing and enforcing network standards and the tiered certification system, coordinating capital campaigns and alumni fundraising across regions, recruiting and vetting PhD-level faculty and leadership for new schools, managing the network-wide competition circuit and celebrating achievements, administering the venture capital fund for graduate entrepreneurs, ensuring HBCU partnership agreements are formalized and beneficial to all parties, and providing technical assistance to schools at all development tiers.

This consortium cannot be housed within a single HBCU—it must be an independent 501(c)(3) with its own board, staff, and budget. However, HBCUs should hold majority governance positions, ensuring the pipeline serves their institutional interests. Initial capitalization of the consortium itself would require $25-50 million to establish offices, hire expert staff, and begin coordinating the network’s development. Regional chapters of the consortium would operate in major areas—the Southeast Chapter, Texas Chapter, Midwest Chapter, West Coast Chapter—each responsible for school development in their territories. These chapters would be staffed by education experts, fundraisers, and facilities planners who understand both K-12 education and HBCU pipelines. The consortium model solves the coordination problem. Without it, well-meaning but disconnected efforts will struggle. With it, alumni know where to direct resources, new schools follow proven models, and the ecosystem develops strategically rather than haphazardly.

With leadership structure established, building this ecosystem requires coordinated action across a decade. Year one should focus on stabilizing and expanding the four remaining Black boarding schools with immediate capital infusions, launching five elite Black day schools in major metropolitan areas with full capitalization and endowments, and establishing formal partnerships between all K-12 institutions and nearby HBCUs. Year two should expand competition programming at all HBCU laboratory schools with PhD-level coaching staffs, launch ten additional elite day schools in strategic regions nationwide, and create the first network-wide competition circuit exclusively for member institutions.

By year three, the network should establish tiered certification for all participating Black schools, regardless of founding date, launch the first network venture capital fund for graduate entrepreneurs, and open five new boarding schools in geographically diverse locations. Year four should scale to thirty total elite day schools and ten boarding schools, establish PhD faculty recruitment pipelines specifically for network schools, and create comprehensive summer programs where students from all network schools can access intensive competition preparation. Finally, year five should see the graduation of the first full cohorts who experienced elementary through high school entirely within network institutions, the achievement of national competition championships by multiple network schools, and network endowments exceeding $2 billion collectively across all institutions.

Within a decade, this network produces tens of thousands of Black students annually receiving world-class education, wins national competition championships regularly, feeds HBCUs with exceptionally prepared students, and becomes self-sustaining through graduate giving and economic activity. The Eight Schools Association took over a century to build their institutional power. With strategic focus and adequate resources, the Black K-12-to-HBCU pipeline can achieve comparable influence in a fraction of that time.

The civil rights movement fought for integration, and those battles were necessary. But sixty years later, the results are mixed. Majority-Black schools face disproportionate closure. Black students in predominantly white institutions navigate isolation and microaggressions. The promise that integration would provide equal access has proven incomplete. The path forward isn’t abandoning integration but building powerful alternatives—Black-controlled institutions that offer excellence on our terms. When the Eight Schools Association sets standards, they do so for their community’s benefit. When they build pipelines to Ivy League schools, they’re securing their children’s futures. African Americans deserve the same institutional sovereignty.

This ecosystem—day schools, boarding schools, laboratory schools, HBCUs, research labs, businesses—creates options. A Black student should be able to receive world-class education from Pre-K through doctoral degree entirely within Black institutions, if they choose. That choice currently doesn’t exist at scale. Building it is the work. The competition focus is merely the entry point—a measurable goal that drives institutional development. But the vision extends far beyond Science Olympiad trophies. It’s about creating an ecosystem where Black excellence is systematically produced, celebrated, and leveraged to build generational wealth and institutional power.

Our children deserve day schools and boarding schools as prestigious as Exeter and Andover—schools that are ours. They deserve laboratory schools as innovative as the most progressive independent schools—schools that feed into our universities. They deserve competition networks as robust as any in America—networks that celebrate Black achievement unapologetically. The infrastructure exists in fragments. The model is proven. What’s required now is collective commitment—alumni investment, HBCU leadership, and community support to build an ecosystem of Black educational excellence that rivals any in the world. Not for integration into existing power structures, but to establish our own. Not just for high school, but from the earliest years through college and career. Not just for the few who can access boarding schools, but for the many who need excellent day schools in their communities. The time for this work is now. The resources exist. The need is urgent. Let’s build.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ClaudeAI.