“Freedom has never been free.” – Medgar Evers

It never ceases to amaze how easily appeased African America can be. We need 40 acres and instead allow ourselves to be given a pot with some dirt in it and are expected to act grateful. Ironically, often we do. “They gave us something” could be a whole mantra that we hear far too often when we need to show our communities that the mantra is “We fight not capitulate”. Time and time again PWIs show that they will put alligator and piranha filled moats around things like law schools, MBAs, and research to ensure that HBCUs never encroach on that institutional power. We get “agreements” that allow PWIs to pick and choose the best and brightest of our undergraduates for their graduate schools. The next Thurgood Marshall cannot come from one of our own HBCU law schools like the late justice but inevitably from a PWI law school where the molding of law and its purpose will be shaped how they see fit. Usually still to their benefit. The flagship HBCU in Mississippi cannot have a law school, it has an agreement. Imagine Ole Miss getting an “agreement” with something in Jackson State’s control. You cannot imagine it because it would never happen.

Historical and Structural Underrepresentation

- Limited Legal Education Options for African Americans: Historically, African Americans were denied access to legal education at predominantly white institutions (PWIs) and were often left with no choice but to attend the few law schools established at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Today, there are only six HBCU law schools:

- Howard University School of Law

- Southern University Law Center

- Texas Southern University Thurgood Marshall School of Law

- Florida A&M University College of Law

- North Carolina Central University School of Law

- University of the District of Columbia David A. Clarke School of Law

- None in Mississippi: Despite Mississippi’s large African American population (nearly 40% of the state), there are no HBCU-affiliated law schools in the state. This lack forces African American students to compete for limited seats at existing law schools, often in environments that may not prioritize their unique needs or cultural experiences.

Historical Context of Discrimination in Mississippi Higher Education

- Systemic Exclusion: For much of the 20th century, African Americans were excluded from attending predominantly white institutions (PWIs) in Mississippi. Segregation laws and practices relegated Black students to underfunded HBCUs, such as Jackson State University.

- Funding Disparities: HBCUs in Mississippi have historically received significantly less funding than PWIs. This underfunding has limited their ability to expand academic offerings and infrastructure, including professional programs like law schools.

Ongoing Disparities

- Resource Inequities: Mississippi’s higher education system continues to show disparities in funding and resources between HBCUs and PWIs. These inequities impact the quality of education and opportunities available to students at HBCUs.

- Underrepresentation in Legal Education: African Americans remain underrepresented in Mississippi’s existing law schools, including the University of Mississippi School of Law and Mississippi College School of Law. These institutions do not adequately address the unique challenges faced by Black students and communities.

- Pipeline Challenges: The lack of professional schools at HBCUs in Mississippi limits pathways for Black students to enter high-impact fields like law, perpetuating disparities in representation and leadership.

Historical Challenges at the University of Mississippi

- Resistance to Integration: The admission of James Meredith in 1962 as the first African American student at Ole Miss was met with violent riots, requiring federal intervention. This historical event illustrates the extreme resistance to racial integration and set the tone for ongoing challenges faced by African American students.

- Legacy of Segregation: The University of Mississippi, like many Southern institutions, has a deeply entrenched history of segregation that continues to influence campus culture and attitudes.

Ongoing Issues Faced by African American Students

- Hostile Campus Environment: Many African American students at Ole Miss report feeling unwelcome or isolated due to a predominantly white student body and lingering racial tensions. Incidents of racism, such as vandalism of monuments and racist social media posts, contribute to a climate of hostility.

- Symbolic Racism: The continued presence of Confederate symbols, including statues and the former use of Confederate imagery in campus traditions, reinforces a sense of exclusion for Black students. Efforts to remove or contextualize these symbols have been slow and controversial.

- Underrepresentation: African American students are underrepresented at Ole Miss compared to the state’s demographics, limiting opportunities for meaningful diversity and inclusion.

- Incidents of Racial Harassment: High-profile incidents, such as the noose placed around the statue of James Meredith in 2014, serve as stark reminders of ongoing racial animosity. These events create psychological distress and reinforce systemic barriers for Black students.

The African American brain drain into predominantly white institutions (PWIs) poses a significant challenge to the mission of historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) like Jackson State University (JSU). Establishing a law school at JSU would address this issue by offering a culturally affirming and accessible path for African American students to pursue legal education. This initiative would help retain talent, strengthen HBCU legacies, and diversify the legal profession.

Understanding African American Brain Drain

- What is Brain Drain? Brain drain occurs when highly capable and motivated individuals, particularly African Americans, leave HBCUs to pursue educational and career opportunities at PWIs. This is often due to the lack of specialized or professional programs, such as law schools, at HBCUs.

- Mississippi’s Context: Mississippi is home to several HBCUs, including Jackson State University, but none of these institutions offer legal education. As a result, aspiring African American lawyers in Mississippi are compelled to attend PWIs such as the University of Mississippi School of Law or Mississippi College School of Law, or leave the state entirely.

Impacts of Brain Drain

- Cultural Isolation: African American students at PWIs often report feelings of isolation and marginalization due to a lack of diversity in faculty, curriculum, and campus culture. This can hinder their academic and professional development.

- Loss of HBCU Legacy: When African American students leave HBCUs for PWIs, they miss the opportunity to benefit from the culturally affirming and supportive environments HBCUs provide. HBCUs foster a sense of community and empowerment that is particularly important in professional fields like law.

- Weakened HBCU Influence: Brain drain diminishes the influence of HBCUs by limiting their ability to produce leaders in fields like law, where African Americans are already underrepresented. This affects the ability of HBCUs to contribute to societal change through their alumni.

The Role of PWIs in African American Brain Drain

- Limited Inclusion: PWIs often fail to adequately support African American students. Issues such as implicit bias, underrepresentation among faculty, and a lack of focus on issues relevant to African American communities make these institutions less ideal for Black students.

- Recruitment of Top Talent: Many PWIs actively recruit top African American talent, which they recognize as essential for promoting diversity. However, these efforts can inadvertently draw students away from HBCUs that would better align with their cultural and educational needs.

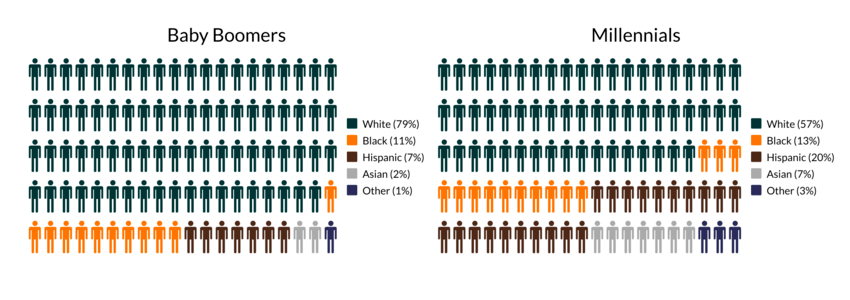

Mississippi became the last state to remove the Confederate battle flag from its state flag in 2020. The birthplace of Medgar Evers who was murdered in his driveway. It is the home of the Freedom Summer that saw three voting rights activists murdered that brought nationwide attention and shun a spotlight on the atrocities. The potential for the impact of a law school at Jackson State University and the creation of the seventh HBCU law school would be profound. African Americans constitute almost 15 percent of the US population and 40 percent of the Mississippi population, but less than 9 percent of Mississippi’s active lawyers are African American. An “agreement” with Ole Miss is highly unlikely to change that paradigm. This is a chance for an African American institution to not take the bull by the horns, but be the bull.

Amplifying the Civil Rights Legacy

- Mississippi’s Legacy of Activism: The state has been at the center of the civil rights movement, with many battles fought for racial equality and justice. A JSU law school could build on this legacy, preparing lawyers to continue the fight against discrimination and inequality.

- Empowering Marginalized Communities: By training lawyers from diverse backgrounds, the law school could directly address issues like voting rights, criminal justice reform, and educational equity—critical areas in a state still grappling with the effects of systemic racism.

The Role of JSU in Filling the Gap

- Addressing Local Needs: A law school at JSU would directly address the absence of African American legal institutions in Mississippi, offering a local and affordable option for students who wish to study law in a supportive environment.

- Culturally Relevant Curriculum: As an HBCU, JSU could design a curriculum that emphasizes the legal challenges faced by African American communities, such as systemic racism, criminal justice reform, and civil rights advocacy.

- Building a Pipeline of Black Lawyers: By increasing access to legal education for African Americans, JSU could help diversify the legal profession and prepare graduates to address the specific legal needs of marginalized communities.

How a JSU Law School Can Address Brain Drain

- Retaining Talent in Mississippi: Establishing a law school at JSU would give African American students in Mississippi the option to pursue legal education at an HBCU without leaving their state or community.

- Culturally Relevant Education: A JSU law school could tailor its programs to address the legal challenges most relevant to African American communities, such as civil rights, voting rights, and criminal justice reform.

- Strengthening HBCU Legacies: By offering a law program, JSU could enhance its reputation as a premier institution for African American education and leadership, attracting top talent to remain within the HBCU ecosystem.

The Need for an Inclusive Legal Education at JSU

- Safe and Supportive Environment: An HBCU law school at Jackson State University would provide a nurturing environment for African American students, free from the racial hostility that has been reported at Ole Miss.

- Focus on African American Legal Issues: A law school at JSU could emphasize areas of law that disproportionately impact Black communities, such as civil rights, voting rights, criminal justice reform, and housing law.

- Addressing the Legacy of Exclusion: By creating a pathway to legal education specifically designed to empower marginalized groups, JSU could challenge the structural inequalities that have persisted in Mississippi’s higher education system.

Broader Benefits of a JSU Law School

- Community Impact: Graduates of a JSU law school would be more likely to practice in underserved and predominantly African American communities, addressing legal deserts in Mississippi and beyond.

- Representation in the Legal Profession: Increasing the number of African American lawyers trained at an HBCU would help diversify the legal profession and create more advocates for systemic change.

- Economic and Cultural Reinvestment: Retaining African American students at JSU would help prevent the economic and cultural losses associated with brain drain, fostering stronger HBCU communities and alumni networks.

Mississippi’s lack of African American legal institutions highlights the urgency of a law school at JSU. Such a school would address historical exclusion, provide a platform for empowerment and justice, and meet the unique legal needs of African American communities. JSU’s law school could play a pivotal role in advancing social justice and transforming the legal profession.

The challenges African American students face at PWIs like the University of Mississippi further emphasize the need for supportive alternatives. A law school at Jackson State University would create an environment where Black legal scholars can thrive, challenging systemic inequities in higher education. By fostering a new generation of African American lawyers, JSU could significantly advance African America’s institutional empowerment, justice, and opportunity across Mississippi and beyond.

It is hard to imagine with the current social and political climate that has seen the Southern “attitude” towards African America emboldened that a partnership or agreement with the flagship institution of that attitude being anything more than cover for continued behavior and a means of a subversive quelling of African American institutional empowerment and independence. The Medgar Evers Law School at Jackson State University located in the capital of the state that is a symbol of power being named after Medgar Evers and a substance of power being a law school in the heart of Dixie. A heart that African America needs to be break.