“It is disappointing that HBCUs and any African American institution for that matter have not figured out yet that the circulation of our social, economic, and political capital with each other at the institutional level is where the acute crisis of closing the wealth gap truly lies. Yet, we still chase colder ice.” – William A. Foster, IV

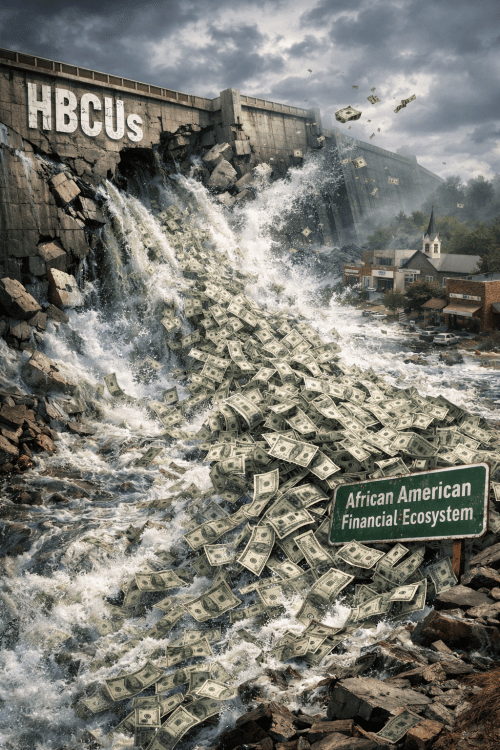

The percentage of PWI dollars that flow into African American owned businesses is likely limited to catering a social event. Beyond that, their dollar never even likely floats pass an African American business. However, HBCUs certainly cannot say the same. HBCU capital leaving the African American financial ecosystem looks like every dam on Earth broke at the same time.

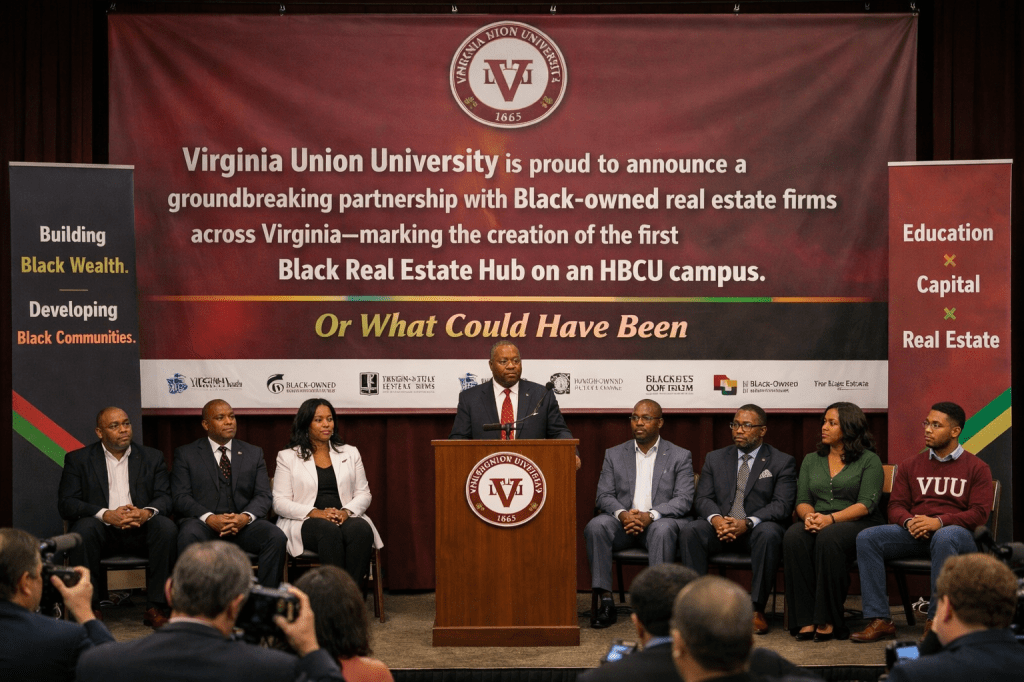

Virginia Union University’s recent announcement of a partnership with Keller Williams Richmond West represents a familiar pattern in HBCU decision-making, one that undermines the very mission these institutions claim to champion. While VUU proudly touts this collaboration as “groundbreaking” and positions it as a pathway to “closing the racial wealth gap,” the partnership reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of how wealth gaps are actually closed. The reality is stark: you cannot close a racial wealth gap by systematically excluding institutions from your own community from the economic opportunities your institution creates.

When HBCUs partner exclusively with non-Black institutions, they create what economists call a “leaky bucket” effect. The money, talent, and social capital generated by these historically Black institutions flow outward to other communities rather than circulating within the African American ecosystem. Every dollar spent with a non-Black vendor, every partnership signed with a non-Black firm, every opportunity directed away from Black-owned businesses represents wealth that could have been building generational prosperity in Black communities—but instead enriches other groups. This is where the fundamental disconnect lies: HBCUs understand the importance of encouraging individual African Americans to support Black-owned businesses, yet these same institutions fail to apply this principle at the institutional level where the real economic power resides.

The conversation about the circulation of the African American dollar has historically focused on individual consumer behavior. We’ve heard for decades about the need for Black consumers to shop at Black-owned stores, bank with Black-owned financial institutions, and hire Black-owned service providers. Studies have shown that a dollar circulates in Asian communities for approximately thirty days, in Jewish communities for around twenty days, in white communities for seventeen days, but in Black communities for only six hours before leaving. This abysmal circulation rate is correctly identified as a critical factor in the persistent wealth gap. But what these discussions almost always miss is that individual consumer behavior, while important, pales in comparison to institutional spending power.

When Virginia Union University signs a multiyear partnership with Keller Williams, it’s not spending a few hundred or even a few thousand dollars. Institutional partnerships involve hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars in direct and indirect economic benefits—facility usage, marketing exposure, student referrals, commission opportunities, and brand association. A single institutional partnership can equal the spending power of hundreds or thousands of individual consumers. Yet HBCUs consistently fail to recognize that their institutional spending decisions have exponentially more impact on wealth circulation than any individual consumer choice their students or alumni might make.

VUU’s partnership with Keller Williams is particularly emblematic of this pattern. According to the announcement, this collaboration will create “the first Keller Williams Real Estate Hub on an HBCU campus in Virginia” and will be “designed to bridge education, entrepreneurship, and real estate into one powerful ecosystem.” The goals are admirable: career readiness, economic mobility, wealth-building opportunities through real estate education and professional pathways. The partnership is positioned as being co-led by members of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Incorporated, with explicit language about sisterhood, brotherhood, and service in action. But here’s the question VUU administrators apparently didn’t ask: Why not create this “powerful ecosystem” with a Black-owned real estate company?

The assumption underlying most HBCU partnerships with non-Black firms seems to be that suitable Black-owned alternatives don’t exist. This assumption is demonstrably false. Black-owned real estate companies operate throughout the United States, including in Virginia and the Richmond area. These firms possess the expertise, resources, and commitment to serve HBCU students and alumni. United Real Estate Richmond, which describes itself as the largest Black-owned real estate firm in the Mid-Atlantic region, operates right in VUU’s backyard. CTI Real Estate is a Black-owned, woman-owned firm serving Virginia and Maryland. Nationally, companies like Braden Real Estate Group—a Black-owned Houston-based brokerage co-founded by Prairie View A&M University graduate Nicole Braden Handy—demonstrate the success of HBCU alumni in building substantial real estate businesses. H.J. Russell & Company, founded in 1952, stands as one of the largest minority-owned real estate firms in the United States. These Black-owned firms have proven track records of success, deep community connections, and explicit missions to build wealth in African American communities. These firms could provide the same—or better—opportunities that Keller Williams offers, with the added benefit of keeping wealth circulating in the Black community.

The difference would be transformative. A partnership with a Black-owned real estate firm would actually contribute to closing the wealth gap. It would demonstrate to students what Black excellence in business looks like. It would create mentorship opportunities with professionals who understand the unique challenges and opportunities facing Black Americans in real estate. It would ensure that the commissions, fees, and other economic benefits generated by the partnership stay within the African American economic ecosystem. Most importantly, it would model the institutional behavior necessary for true wealth accumulation—showing students that circulation of Black dollars must happen at every level, not just in their personal spending habits.

But to truly understand what institutional circulation looks like, consider this scenario: An African American real estate investment firm—owned by an HBCU alumnus and employing HBCU graduates as project managers, analysts, and development specialists—decides to develop a mixed-use building in Richmond. The firm uses Braden Real Estate Group to acquire the land. They secure financing from an African American bank like OneUnited Bank or Liberty Bank, supplemented by an investment syndicate of African American investors. The construction is handled by an African American-owned construction company like H.J. Russell & Company. When the transaction closes, it’s processed through Answer Title & Escrow LLC, the Black-owned title company founded by University of the District of Columbia alumna Donna Shuler. The property management contract goes to another Black-owned firm. The legal work is handled by Black attorneys. The accounting is done by a Black-owned firm.

This is what institutional circulation actually looks like. In this single development project, wealth circulates through multiple Black-owned institutions at every stage of the transaction. The bank earns interest income that it can then lend to other Black businesses and homeowners. The title company generates revenue that allows it to hire more staff and take on larger projects. The construction company builds its portfolio and capacity to compete for even bigger developments. The real estate investment firm creates returns for its Black investors and proves the viability of Black-owned development companies. The project managers and analysts gain experience that prepares them to start their own firms. Every single point in the transaction keeps wealth circulating within the African American economic ecosystem, building institutional capacity, creating jobs, generating returns, and proving that Black-owned institutions can handle sophisticated, large-scale projects.

Now contrast that with what happens when VUU partners with Keller Williams. Students may get training and even jobs as real estate agents, but the institutional wealth flows to Keller Williams—a non-Black company. The commissions generated by VUU-affiliated agents enrich Keller Williams’ franchise system. The brand association benefits Keller Williams’ reputation. The networking opportunities primarily connect students to Keller Williams’ existing (predominantly non-Black) networks. And when these students eventually facilitate property transactions, the ancillary services—financing, title work, legal services—typically flow to whatever institutions Keller Williams recommends, which are unlikely to be Black-owned.

The VUU-Keller Williams partnership might help individual Black students enter the real estate industry, but it does absolutely nothing to build the Black-owned institutional infrastructure necessary for true wealth building. In fact, it actively undermines that infrastructure by directing institutional resources and opportunities away from Black-owned firms. VUU essentially takes Black talent, students who could be building careers with Black-owned firms, and channels them into a non-Black institution, teaching them that Black institutions aren’t capable of providing the same opportunities.

This is the critical insight that HBCUs continue to miss: institutional circulation of capital is what builds lasting economic power. When individual Black consumers support Black businesses, they create important but limited impact. One person shopping at a Black-owned grocery store or banking with a Black-owned bank makes a difference, but a small one. When Black institutions support Black businesses, they create transformative, generational impact. An HBCU that partners with Black-owned banks, construction companies, real estate firms, technology providers, and service companies doesn’t just create individual transactions it builds an entire ecosystem of mutually reinforcing institutions that grow stronger together. This institutional ecosystem then has the power to compete with non-Black institutions, create opportunities at scale, and genuinely close wealth gaps.

Think about what would happen if every HBCU made a commitment to work exclusively with Black-owned institutions whenever viable alternatives exist. Imagine if all 101 HBCUs banked with Black-owned banks, used Black-owned construction companies for campus buildings, partnered with Black-owned real estate firms for student housing and community development, contracted with Black-owned technology companies for IT services, and hired Black-owned firms for legal, accounting, and consulting work. The combined institutional spending power of HBCUs would transform the Black business landscape. Black-owned banks would have hundreds of millions in deposits, allowing them to make larger loans and compete for more business. Black-owned construction companies would have steady revenue streams that would allow them to invest in equipment, hire skilled workers, and bid on larger projects. Black-owned real estate firms would have the institutional backing to compete for major developments. Black-owned technology companies would have the resources to innovate and scale.

But beyond the immediate economic impact, this institutional circulation would create something even more valuable: proof of concept. When Alabama State University chooses a Black-owned bank to handle a $125 million transaction, it proves that Black-owned financial institutions can handle sophisticated, large-scale deals. When VUU partners with a Black-owned real estate firm to create a campus-based real estate hub, it proves that Black-owned companies can deliver the same quality and scale as non-Black competitors. When HBCUs consistently work with Black-owned construction companies, law firms, accounting firms, and consulting companies, they build a track record of success that these firms can point to when competing for other major contracts. This institutional validation is precisely what Black-owned businesses need to break through the barriers that have historically excluded them from large-scale opportunities.

VUU’s partnership is not an isolated incident, it’s part of a troubling pattern. As HBCU Money has documented, only two HBCUs are believed to bank with Black-owned banks, meaning well over 90 percent of HBCUs do not bank with African American-owned financial institutions. This mirrors the broader pattern where over 90 percent of African Americans who attend college choose non-HBCUs, and in both cases, neither Black-owned banks nor HBCUs are able to fulfill their potential without the patronage and investment of those they were built to serve. Alabama State University’s $125 million decision to partner with a non-Black financial institution exemplifies what can be called “Island Mentality”—the failure of HBCUs to connect with and support the African American private sector. When Alabama State University had the opportunity to work with Black-owned banks and financial institutions, they chose to look elsewhere. Consider the irony: Howard University, African America’s flagship HBCU, partnered with PNC Bank, a Pittsburgh-based institution with over $550 billion in assets, more than 100 times the combined assets of all remaining Black-owned banks to create a $3.4 million annual entrepreneurship center. Meanwhile, Industrial Bank, a Black-owned institution with $723 million in assets, operates right in Howard’s backyard. PNC Bank’s executive team commanded $81 million in compensation in 2022 alone, while only one Black-owned bank in America has assets exceeding $1 billion. These decisions, like VUU’s partnership with Keller Williams, send a devastating message: even historically Black institutions don’t believe Black-owned businesses are worthy of their partnership.

The impact extends beyond symbolism. Every time an HBCU chooses a non-Black partner when Black alternatives exist, it represents lost revenue for Black-owned businesses that could have grown stronger, hired HBCU graduates, and created more opportunities. It represents missed networking opportunities for students who could have built relationships with Black business leaders. It represents weakened community ties that could have been strengthened through institutional support. It represents reduced political capital for the Black business community, which needs institutional backing to compete for larger contracts. And it perpetuates stereotypes about the capability and reliability of Black-owned businesses.

Let’s be clear about what “closing the wealth gap” actually requires. According to the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances, the median wealth of white families is approximately ten times greater than that of Black families. This gap didn’t emerge overnight, and it won’t close through symbolic gestures or partnerships that funnel Black talent and capital into non-Black institutions. Closing the wealth gap requires wealth creation within the Black community through business ownership and entrepreneurship. It requires wealth circulation that keeps dollars moving through Black-owned businesses before leaving the community. It requires wealth accumulation through strategic investments in Black-owned assets. And it requires wealth transfer across generations through education, mentorship, and institutional support.

When VUU partners with Keller Williams instead of a Black-owned real estate company, it fails on every single one of these requirements. The wealth created by student success in real estate will flow to Keller Williams and its predominantly non-Black agents. The circulation of capital will happen outside the Black community. The accumulation will benefit non-Black wealth holders. And the transfer of knowledge and opportunity will lack the cultural competency and community commitment that comes from working with Black-owned institutions. Most critically, VUU misses the opportunity to demonstrate to its students how institutional circulation of capital works, teaching them instead that even Black institutions should look outside their community for partnerships when it matters most.

The example of what institutional circulation could look like in real estate development isn’t theoretical it’s entirely possible right now with existing Black-owned institutions. When Donna Shuler founded Answer Title & Escrow LLC as a University of the District of Columbia alumna, she created exactly the kind of institutional capacity that makes the full-circle Black real estate ecosystem viable. As she explained in her interview with HBCU Money, title companies play a crucial role in every real estate transaction—they ensure clear ownership, coordinate closings, prepare legal documents, collect funds, and issue title insurance. Having a Black-owned title company means that millions of dollars in fees and service charges stay within the Black community rather than flowing out. Combined with Black-owned banks providing financing, Black-owned real estate firms handling acquisitions, Black-owned construction companies building the projects, and Black-owned development firms managing the entire process, you create a complete ecosystem where institutional wealth circulates multiple times before leaving the community.

This is what VUU could have created with its real estate initiative but chose not to. Instead of building an ecosystem where Black institutions strengthen each other, VUU created a pipeline that extracts Black talent and channels it into a non-Black institution. Students will learn real estate from Keller Williams, make connections through Keller Williams networks, and likely facilitate transactions that benefit Keller Williams and its associated service providers. The institutional wealth created by VUU’s endorsement and student pipeline flows entirely out of the Black community.

HBCUs often justify these partnerships by arguing that non-Black firms offer broader networks, more resources, or greater reach. This argument is both self-fulfilling and self-defeating. It’s self-fulfilling because when HBCUs consistently choose non-Black partners, they ensure that Black-owned businesses never gain the institutional backing needed to compete at scale. How can Black-owned real estate companies build the same networks as Keller Williams when HBCUs, the institutions that should be their natural partners, consistently choose their competitors? It’s self-defeating because it undermines the very purpose of HBCUs. These institutions were created because the existing educational ecosystem excluded Black Americans. They thrived by building their own networks, creating their own opportunities, and supporting each other. The suggestion that HBCUs now need to partner with non-Black institutions to succeed represents a fundamental abandonment of the HBCU mission and the institutional circulation principle that should guide their operations.

Imagine if VUU had instead announced a partnership with a coalition of Black-owned real estate companies. The announcement might have read: “Virginia Union University is proud to announce a groundbreaking partnership with Black-owned real estate firms across Virginia marking the creation of the first Black Real Estate Hub on an HBCU campus. This collaboration goes beyond sponsorship to create career readiness, economic mobility, and wealth-building opportunities for VUU students, alumni, and the Richmond community through real estate education, entrepreneurship, and professional pathways led by successful Black business owners including HBCU alumni. Students will learn not just how to sell houses, but how to build generational wealth through development, investment, and institutional deal-making within the Black business ecosystem. They will receive training from firms like United Real Estate Richmond, Braden Real Estate Group, and other Black-owned companies, with pathways to internships and employment that keep talent and capital circulating within the African American community. The initiative will explicitly connect students with Black-owned banks for financing education, Black-owned title companies for transaction processing, and Black-owned development firms for career opportunities in the full spectrum of real estate activities.”

Such a partnership would demonstrate commitment to the Black business community, create mentorship pipelines between Black students and Black business leaders, build economic power by concentrating resources in Black-owned institutions, establish replicable models for other HBCUs to follow, and generate authentic wealth-building that actually closes gaps rather than widening them. It would teach students the most important lesson about wealth building: that institutional circulation of capital within your community is what creates lasting prosperity, not individual success stories that extract value from the community.

Beyond economics, these partnership decisions carry enormous social and political implications. When HBCUs choose non-Black partners, they signal to their students, alumni, and communities that Black-owned businesses are insufficient, unreliable, or less capable. This message has devastating ripple effects. Students at HBCUs should graduate believing they can build successful businesses that serve their communities and compete at the highest levels. They should see their institutions modeling the behavior they’re encouraged to adopt. Instead, they witness their own universities choosing non-Black partners, learning an implicit lesson about the supposed superiority of non-Black institutions. They learn that while individual Black consumers should support Black businesses, institutions don’t have to follow the same principle. This creates a fundamental contradiction that undermines the economic empowerment message entirely.

Consider the message VUU sends with its Keller Williams partnership: “We’ll teach you to be real estate professionals, but we don’t believe Black-owned real estate companies are good enough to partner with us.” What are students supposed to take from that? That they should aspire to work for Black-owned firms, or that they should aim for the “real” opportunities at non-Black companies? That Black businesses can compete at the highest levels, or that even Black institutions don’t really believe that? The implicit message is devastating, and it’s reinforced every time an HBCU makes a major partnership announcement with a non-Black firm when Black alternatives exist.

This dynamic also weakens the political capital of the Black business community. When even HBCUs won’t support Black-owned businesses, it becomes nearly impossible for these firms to argue they deserve a seat at the table for major contracts, government partnerships, or policy decisions. If historically Black institutions don’t believe Black businesses are capable of handling significant partnerships, why would predominantly white institutions, corporations, or government agencies think differently? HBCUs, by failing to partner with Black-owned institutions, actively undermine the credibility and viability of the very businesses that could drive wealth creation in African American communities.

The solution isn’t complicated, though it requires courage and commitment. HBCUs must conduct systematic audits of all major partnerships and vendor relationships to identify where Black-owned alternatives exist. They must establish procurement policies that prioritize Black-owned businesses when quality and capability are equivalent. They should create development programs to help emerging Black-owned businesses build the capacity to serve as HBCU partners. They need to build collaborative networks connecting HBCUs with Black-owned banks, real estate firms, construction companies, technology providers, and other businesses. They must measure and report on the percentage of institutional spending directed to Black-owned businesses, creating transparency and accountability. And they need to educate all stakeholders—boards, administrators, faculty, students, and alumni—about why these partnerships matter for wealth gap closure and why institutional circulation of capital is the key to building lasting economic power.

Some will argue this approach is discriminatory or inefficient. This objection ignores history and reality. HBCUs exist because discrimination created the need for separate Black institutions. Having addressed educational exclusion by building their own colleges, it’s logical and necessary to address economic exclusion by building supportive business ecosystems. The focus on institutional circulation isn’t about excluding others; it’s about finally including Black-owned institutions in the economic opportunities that Black institutions create. It’s about recognizing that the same principle we apply to individual consumer behavior of circulate dollars in your community applies with exponentially greater impact at the institutional level.

The choice facing HBCUs is stark: continue operating as isolated islands that happen to serve Black students, or become integral parts of a thriving African American institutional ecosystem that builds collective power and prosperity. Virginia Union University’s partnership with Keller Williams, like Alabama State University’s financial decisions before it, represents the island mentality. These institutions take Black talent, Black energy, and Black resources, then channel them into non-Black institutions that have no structural commitment to Black community wealth-building. They preach to students about supporting Black businesses while their own institutional dollars flow to non-Black partners.

The real estate development scenario described earlier where an HBCU alumnus-owned development firm works with Braden Real Estate Group, Answer Title, a Black-owned bank, and a Black-owned construction company isn’t a fantasy. All of these institutions exist right now. The only thing preventing this kind of institutional circulation from becoming the norm rather than the exception is the willingness of HBCUs to make it a priority. When HBCUs choose to partner with Black-owned institutions, they don’t just create individual transactions they validate and strengthen an entire ecosystem of Black-owned businesses that can then compete for even larger opportunities.

True wealth gap closure requires HBCUs to fundamentally reimagine their role. They must see themselves not as individual institutions competing for resources and prestige, but as anchor institutions responsible for building and sustaining a broader African American economic ecosystem. This means prioritizing partnerships with Black-owned banks, real estate companies, construction firms, technology providers, and other businesses even when doing so requires more effort, more creativity, or more patience. It means recognizing that institutional circulation of capital is what transforms individual Black success stories into generational Black wealth accumulation. It means understanding that HBCUs have the power to create the very ecosystem they claim doesn’t exist by directing their substantial institutional resources to Black-owned businesses.

The question isn’t whether Black-owned alternatives exist. They do. The question is whether HBCU leaders have the vision, courage, and commitment to build an economic ecosystem that actually closes the wealth gap rather than simply talking about it. Until HBCUs make this fundamental shift, until they recognize that institutional circulation of capital is the key to wealth building and start directing their partnerships, contracts, and spending to Black-owned institutions these announcements about “groundbreaking partnerships” that close the wealth gap will remain what they are today: well-intentioned rhetoric that masks the continued extraction of Black wealth and talent for the benefit of other communities.

Individual African Americans can only do so much with their consumer dollars. The six-hour circulation rate in Black communities is a problem, but it’s a problem that individual behavior alone cannot solve. The real power lies at the institutional level. When an HBCU spends $10 million on a construction project with a Black-owned firm, that’s not the equivalent of 10,000 individual consumers each spending $1,000—it’s exponentially more powerful because institutional spending validates capacity, builds track records, creates jobs at scale, and proves viability in ways that individual transactions never can. But HBCUs, with their millions in institutional spending power, their influence over thousands of students and alumni, and their role as anchor institutions in Black communities, have the power to transform the economic landscape. They just need to recognize that the principle of dollar circulation they teach their students applies with even greater force to their own institutional behavior.

Until HBCUs start practicing institutional circulation of capital, until they recognize that every major partnership, every significant contract, and every spending decision is an opportunity to strengthen Black-owned institutions and build the ecosystem necessary for true wealth creation they will continue to be part of the problem rather than the solution to the wealth gap they claim to want to close. The infrastructure exists. The capable Black-owned businesses exist. The only thing missing is the institutional will to make Black economic ecosystem-building a priority over convenience, familiarity, or the perceived prestige of partnering with established non-Black firms. The choice is clear: HBCUs can continue channeling Black talent and capital out of the community, or they can finally commit to the institutional circulation that makes wealth gap closure actually possible.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ClaudeAI.