“The wealthiest boosters and donors to a PWI rarely ever played sports, but they did go build companies and a lot of wealth. Boosters spend hundreds of millions a year to compete with their friends and business competition from rival schools. The money spent is a bigger game than what happens on the field.” – William A. Foster, IV

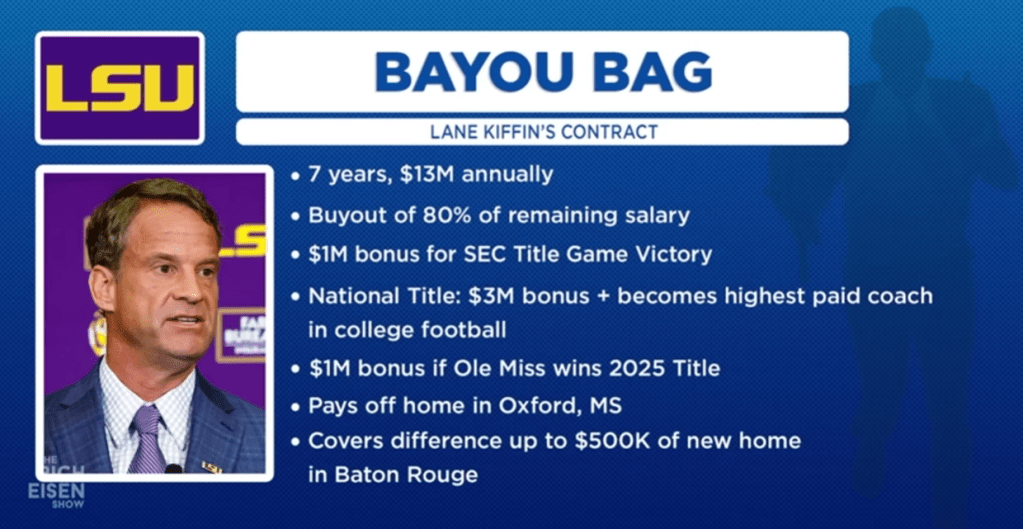

The image circulating across sports media this week says everything without trying to explain anything at all. LSU’s new contract offer to Lane Kiffin — seven years at $13 million annually, stacked with multimillion-dollar bonuses, home buyouts, and housing subsidies looks less like a coaching contract and more like a sovereign wealth transaction. It is the kind of deal only an institution backed by generational wealth, mega-boosters, and a national alumni base at the upper end of the economic ladder could produce. Yet every few months a familiar chorus resurfaces insisting that if “only the top African American athletes chose HBCUs,” the financial gap in college athletics would close. The narrative is compelling, emotional, and rooted in cultural longing, but it remains economically false.

The fantasy is seductive: if only more premier African American athletes chose HBCUs, our athletic programs could compete with Predominantly White Institutions (PWIs). If only we could land that five-star recruit, sign that top quarterback, or attract that elite basketball prospect, everything would change. The dream persists in alumni conversations, on social media, and in aspirational fundraising campaigns. But the dream is built on a fundamental misunderstanding of what actually drives college athletic success and it’s costing HBCUs resources they can’t afford to waste. The numbers tell a story that talent alone cannot rewrite.

Lane Kiffin’s new contract with LSU pays him approximately $13 million annually, making him one of the highest-paid coaches in college football. To put this in perspective, Southern University’s entire athletic department operates on total revenues of $18.2 million for fiscal year 2025-2026. One coach at a PWI earns over 70 percent of what an entire HBCU athletic department generates in revenue. This isn’t an aberration it’s the system working exactly as designed.

The disparity becomes even starker when you examine what funds these massive operations. According to an audit report, Southern University Athletics had total revenue of $17.3 million and expenses of $18.9 million in fiscal year 2023, creating a deficit of $1.5 million. Meanwhile, PWI athletic departments operate with budgets in the hundreds of millions. The athletes on the field, no matter how talented, cannot bridge this chasm.

What truly separates PWI athletic programs from HBCU programs isn’t the talent of 18-22 year-olds playing the games. It’s the economic power of the institutions behind them specifically, the size, wealth, and giving capacity of their alumni bases. According to Georgetown University, PWI graduates earn an average of $62,000 annually, compared to HBCU graduates who earn around $51,000. But the income gap is just the beginning of the story. The real disparity lies in generational wealth accumulation and the sheer number of potential donors.

Major PWIs have alumni bases numbering in the hundreds of thousands, often spanning generations of families who have accumulated significant wealth over decades. These institutions benefit from alumni who are CEOs, hedge fund managers, real estate developers, and executives at Fortune 500 companies. Their boosters can write seven-figure checks without blinking. When they want to retain a coach or upgrade facilities, they simply open their checkbooks.

HBCUs represent around 3% of America’s colleges, yet account for less than 1% of total U.S. endowment wealth. The endowment funding gap stands at approximately $100 to $1—for every $100 a PWI receives in endowment money, HBCUs receive $1. This isn’t just about annual giving; it’s about the compound interest of generational investment that HBCUs have never had the opportunity to build.

Corporate sponsors don’t pay for athletic excellence they pay for eyeballs and access to affluent consumer bases. When companies decide where to invest their marketing dollars, they’re calculating the purchasing power and professional networks they can reach through an institution’s alumni base. A company sponsoring a PWI athletic program gains access to hundreds of thousands of alumni with significant disposable income and decision-making power in corporations. The athletes are just the entertainment that delivers this audience. The actual product being sold is access to the alumni network—for recruiting employees, marketing products, and building business relationships.

This is why even if every top African American athlete chose HBCUs, the sponsorship dollars wouldn’t automatically follow. The economic fundamentals would remain unchanged. Companies invest based on return on investment calculations that are tied to alumni wealth and network size, not solely to on-field performance.

The belief that athletic success drives institutional prosperity is perhaps the most dangerous delusion facing HBCU leadership. Even among PWIs, only a tiny fraction of athletic programs actually turn a profit. Most operate at a loss that’s subsidized by the broader university budget, student fees, and institutional transfers. Southern University’s budget shows $2.2 million in “Non-Mandatory Transfer” and $1.4 million in “Athletic Subsidy”—meaning the institution itself must subsidize athletics with nearly $3.6 million in institutional funds. This is money diverted from academic programs, faculty salaries, research, and student services to keep athletic programs afloat.

The PWI athletic model works for PWIs not because athletics are inherently profitable, but because they can afford the losses. They have massive endowments, substantial state funding, and alumni donor bases that can absorb deficits while still funding academic excellence. HBCUs don’t have this luxury. When an HBCU runs a $1.5 million athletic deficit while struggling to pay competitive faculty salaries, upgrade outdated classroom technology, or fund research initiatives, the opportunity cost is devastating. That deficit represents scholarships not awarded, professors not hired, and academic programs not developed.

Some HBCU advocates point to conference television deals and NCAA tournament appearances as potential revenue sources. But here again, the math is unforgiving. Major PWI conferences negotiate billion-dollar television contracts because they deliver large, affluent viewing audiences that advertisers covet. The Big Ten and SEC don’t command massive TV deals because their athletes are more talented they command them because their alumni bases represent valuable consumer demographics. The SWAC and MEAC can’t replicate these deals because they don’t deliver the same audience size and purchasing power, regardless of the talent on the field. Even if HBCUs somehow assembled teams that won national championships, the structural economic advantages would remain with PWIs.

Here’s what proponents of athletic investment don’t want to acknowledge: the marginal difference in talent between a five-star recruit and a three-star recruit is minimal compared to the massive difference in institutional resources. A slightly more talented roster cannot overcome a 10-to-1 or 100-to-1 resource disadvantage.

Consider the logistics: While an HBCU football program might struggle to afford charter flights for the team, PWI programs have dedicated planes, state-of-the-art training facilities, nutritionists, sports psychologists, and medical staffs that rival professional franchises. They have recruiting budgets that allow them to identify and court prospects nationally. They have video coordinators, analysts, and support staff that outnumber many HBCU athletic departments entirely. The game is won with infrastructure, coaching depth, medical support, nutrition, facilities, and recovery technology not just with the athletes on scholarship. And these resources require the kind of sustained, massive funding that only comes from large, wealthy alumni bases and major corporate partnerships.

There is an alternative model that makes sense for HBCUs: the Ivy League approach. Ivy League schools have chosen not to compete in the athletic arms race. They don’t offer athletic scholarships for football. They emphasize academic excellence while maintaining competitive but not dominant athletic programs. Their alumni networks and institutional prestige are built on academic achievement, research output, and professional success not athletic championships.

For HBCUs, this model offers a realistic path forward. Focus resources on academic excellence, research capabilities, and entrepreneurship. Build prestige through intellectual output, not athletic performance. Create value through what HBCUs have always done best: developing future leaders, producing groundbreaking research, and serving their communities.

The Ivy League proves that institutional prestige and alumni loyalty can thrive without major athletic success. No one questions Harvard’s or Yale’s institutional value because their football teams don’t win national championships. Every dollar spent trying to compete in the PWI athletic model is a dollar not invested in what could actually transform HBCU economic outcomes: research infrastructure, entrepreneurship programs, endowment building, and academic excellence.

Research shows that more than half of all students at HBCUs experience some measure of upward mobility, and upward mobility is about 50 percent higher at HBCUs than PWIs. This is the actual competitive advantage HBCUs possess their ability to transform the economic trajectories of students from under-resourced communities. This mission deserves full investment, not the scraps left over after athletic departments consume resources. If HBCUs invested the millions currently subsidizing athletic deficits into research grants, business incubators, technology transfer offices, and endowed professorships, they could create sustainable revenue streams while fulfilling their core mission. They could become engines of wealth creation for African American communities rather than junior varsity versions of PWI athletic programs.

Admitting you can’t win an unwinnable game isn’t defeat it’s strategic wisdom. HBCUs should stop trying to beat PWIs at a game rigged by structural economic advantages they will never possess. Instead, they should redefine success on their own terms.

This means:

Rightsizing athletic budgets to reflect institutional resources and priorities, accepting that competing for national championships in revenue sports isn’t financially viable or strategically wise.

Investing in niche sports and athletic experiences that can be competitive without massive resource requirements and that build campus community without drowning budgets.

Redirecting resources toward academic distinction, particularly in high-demand fields like STEM, healthcare, and technology where HBCU graduates can command premium salaries and build generational wealth.

Building research infrastructure that attracts grants, creates intellectual property, and establishes HBCUs as innovation centers rather than athletic also-rans.

Developing entrepreneurship ecosystems that turn students into business owners and job creators, building the kind of economic power that generates sustained institutional support.

Creating HBCU-specific tournaments and competitions where these institutions can showcase their talents to their communities without subsidizing PWI athletic departments through guarantee games.

The African American community’s love for HBCU athletics is real and deep. The pageantry of HBCU homecomings, the tradition of the bands, the pride of seeing young Black excellence on display these matter. But love sometimes means making hard choices about where to invest limited resources for maximum impact. The question isn’t whether HBCUs should have athletic programs. The question is whether they should bankrupt their academic missions chasing a competitive model they can never win, designed by and for institutions with 100 times their resources.

One coach earning $13 million. One entire athletic department operating on $18 million. The math isn’t subtle. The choice shouldn’t be either.

Until HBCUs build alumni bases with the size, wealth, and giving capacity to compete in the modern college athletic arms race, pursuing the PWI model isn’t ambition it’s financial suicide. The path to HBCU prosperity runs through classrooms and laboratories, not football stadiums and basketball arenas. It’s time to stop chasing someone else’s game and start winning our own.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ClaudeAI.