“Everything that I’ve gone through informs me and my opinions in a way, I guess because I am a child of segregation. I lived through it. I lived in it. I was of it.” – Samuel L. Jackson

One thing most financially literate people realize is that it is not how much you make, but it is how much you keep. Those who are of a wealth building mindset realize it is not how much you keep, but how much of your capital is actually working to make you wealthier without your labor being attached to it. African American individuals, households, and institutions struggle in both cases, but mightily in the latter. Most African American wealth, as highlighted by the amount of time the African American dollar remains in our community (less than 6 hours), does little to no work for the wealth building of those three entities. A major reason for this is that African American individuals, households, and yes, even institutions put little to none of their money in African American institutions – ironically.

Economic Disparities

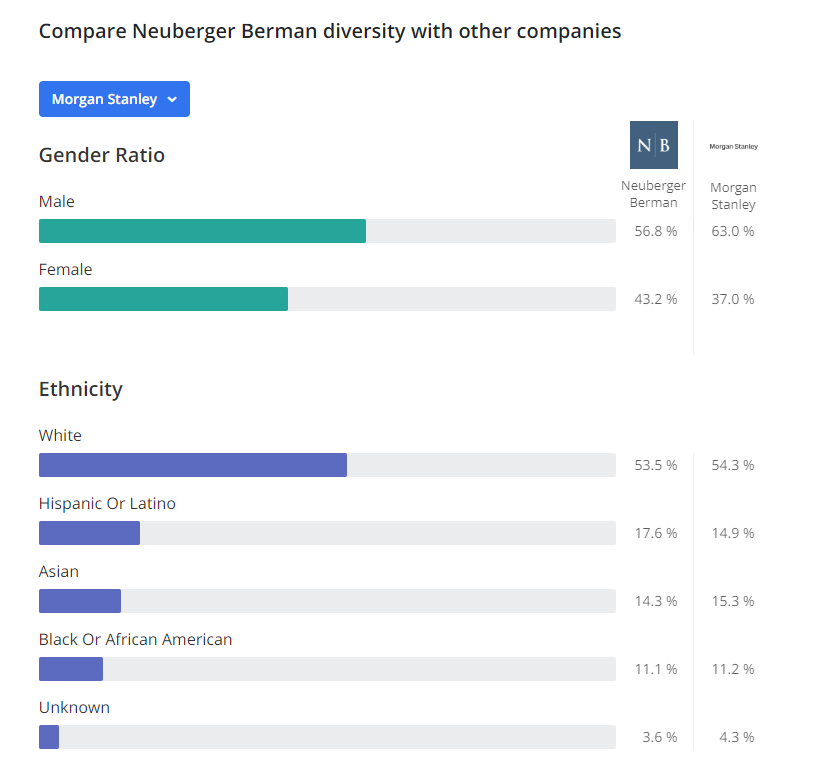

“According to a report by the Federal Reserve, the median net worth of African American households headed by someone aged 55-64 (who would generally be considered Baby Boomers) was around $39,000 in 2019. This is substantially lower than the median net worth of European American households in the same age group, which was around $184,000 in 2019. It’s important to note that there is significant variation within both groups, and wealth is influenced by a range of factors including income, education, and access to resources.”

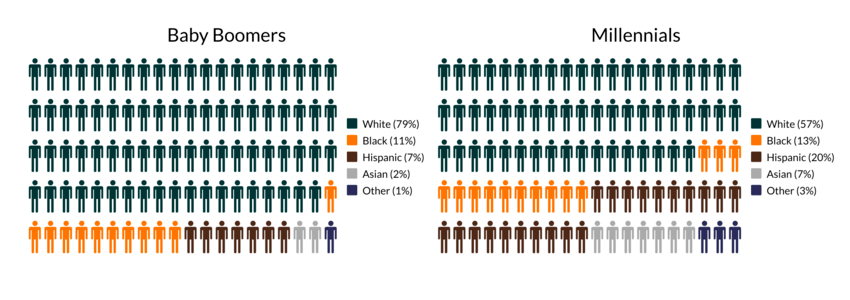

Insider Intelligence gives a generational demographic breakdown reporting that, “Baby boomers were the largest living adult population until 2019. According to the US Census Bureau, US boomers have remained the second-largest population group in 2022, comprised of 69.6 million people ages 58 to 76.” And Statista reports that there are 43.26 million Boomer households meaning that approximately 4.8 million of those are African American. This then puts African American Baby Boomer wealth at approximately $187.2 billion – but what of it?

Each eldest generation will push wealth forward one way or another. Where it flows though can be largely up to the person. Some will push it to the next generation of family and friends, charities and organizations, and there are a host of other options of where money can find itself as one begins to consider their legacy both in the here and now or from the beyond. One things is crystal clear though from a Brookings Institute study, African Americans are falling behind with every passing generation, “30% of European American households received an inheritance in 2019 at an average level of $195,500 compared to 10% of African American households at an average level of $100,000.” African Americans both receive 50 percent less than their European American counterpart and European Americans are three times more likely to get an inheritance than their African American counterpart – but again what of it?

While the wealth of even African American Baby Boomers is not that of their counterparts, it should have the opportunity to make far more considerable impact than it probably actually will. As African American baby boomers age, a significant transfer of wealth is expected to occur. This presents an opportunity for younger generations to invest in education, home ownership, and entrepreneurial ventures. However, research indicates that many African American families face systemic barriers, such as lower access to financial resources and education, which could impact how this wealth is utilized and preserved.

Despite the considerable wealth held by baby boomers, economic disparities persist within the African American community and its institutions. Issues such as income inequality, lack of business ownership, access to African American owned financial institutions, limited access to financial literacy resources, and a disconnected institutional ecosystem can hinder the effective management and growth of inherited wealth. Addressing these disparities will be crucial in ensuring that future generations can leverage this wealth for long-term benefits.

Philanthropy and Community Investment

Many African American baby boomers are inclined to support causes that uplift their communities. This philanthropic inclination could lead to increased investment in African American nonprofits, education initiatives, and other community organizations. By directing funds towards institutional development, these donors can help address systemic issues and create lasting change.

Financial Planning and Literacy

The management of this wealth will largely depend on the financial literacy of both the current baby boomer generation and their heirs. Increasing access to financial education, resources, and African American owned financial institutions is essential to ensure that wealth is not only preserved but also strategically invested. Programs aimed at enhancing financial connectivity between African American households and African American financial institutions within the African American community can play a significant role in maximizing the impact of this wealth.

The fate of the $188 billion in wealth held by African American baby boomers is not just about the transfer of assets; it’s about how those assets can be utilized to build a stronger future for the community. By focusing on education, philanthropy, and addressing systemic barriers, there is potential for this wealth to make a profound impact on the lives of future generations. Ensuring that this wealth is effectively managed and directed towards meaningful causes will be crucial in shaping a more equitable and prosperous future for the African American community. In the end, the only real question is how much of the $188 billion will end up in African American institutions. Whether those organizations be African American social, economic, or political institutions is up to the household, but this is the most acute potential for institutional transformation that African America will have seen since 1865.

Disclosure: This article was assisted by NOVA AI and ChatGPT.