“In the absence of state support, those with capital must decide: will they merely enjoy the benefits of a stable society—or invest in the institutions that make it possible?”

— Arielle Morgan, Senior Fellow, Institute for Civic Infrastructure

The withdrawal of $1.1 billion in federal funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting is not merely a fiscal adjustment—it is a structural dislocation. It marks the effective end of a decades-long social contract in which the U.S. government ensured the existence of a nationwide, non-commercial broadcasting ecosystem intended to serve the public interest. For PBS, NPR, and their hundreds of affiliate stations across the country, the clock is now ticking toward an uncertain future.

But if the U.S. government is no longer willing to fund public broadcasting, another powerful bloc may have to: the ultra-wealthy and the corporations that have long built brand equity on the back of public trust and public platforms. In other words, the very elite who most benefit from stability, reliable information, and a functioning democracy may now be expected to underwrite one of its most foundational institutions.

The price tag? $27.5 billion.

A Simple, Uncomfortable Equation

To replace $1.1 billion in federal funding with investment returns, the equation is straightforward. Using a conservative draw rate of 4%—commonly applied by universities and foundations to ensure long-term preservation of capital—an endowment of $27.5 billion would be required to generate that annual payout.

This is not a charity exercise. It is a capital strategy.

To reach this target, two basic donor models stand out:

- 275 individuals contributing $100 million each

- 2,750 individuals contributing $10 million each

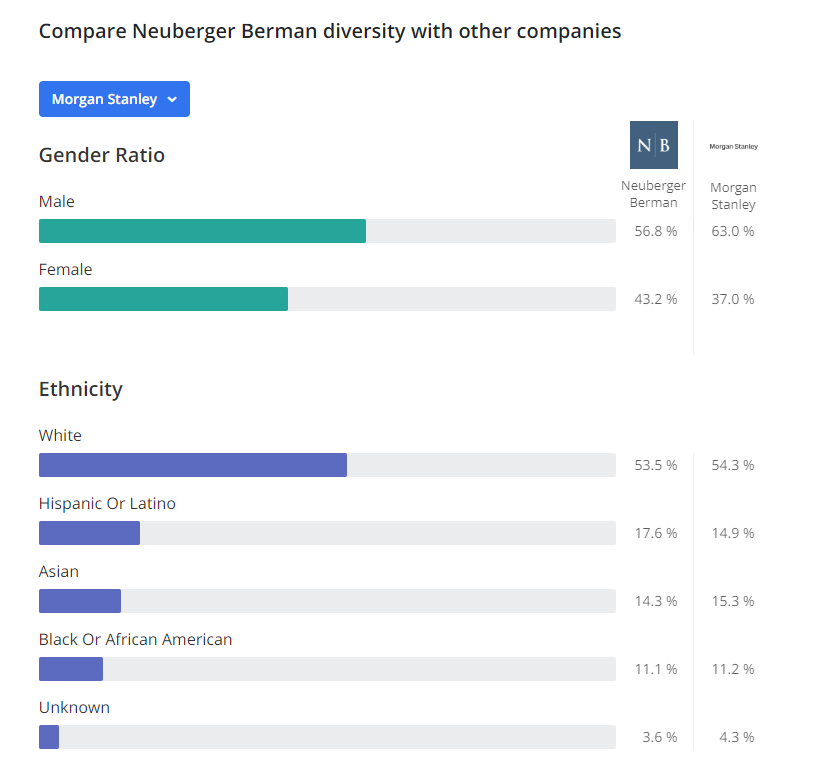

These figures are within striking distance of the top echelon of American wealth. As of 2024, the United States had over 800 billionaires and more than 23,000 centi-millionaires (individuals with $100 million or more in net worth). Put bluntly, it would require only 1.2% of America’s centi-millionaires to secure the future of public broadcasting in perpetuity.

What’s at Stake for the Elite

There is a growing recognition—even among the ultra-wealthy—that civil society must be preserved, even if governments no longer have the capacity or political will to do so. The fragility of liberal democracy, demonstrated by political polarization, misinformation, and institutional distrust, poses long-term risks not only to the electorate but also to markets, capital flows, and reputational value.

Public broadcasting—independent, educational, and widely trusted—has long been a stabilizing force in this ecosystem. Its reach into rural towns, inner cities, and suburban households makes it a conduit for shared narratives and factual baselines. It is not exaggeration to say that NPR and PBS, through All Things Considered, NewsHour, Frontline, and Sesame Street, have helped preserve a measure of social cohesion in a deeply divided country.

For the ultra-wealthy, losing this infrastructure would not simply be a cultural loss. It would be a strategic risk.

Hence the question: if the state won’t fund it, why won’t they?

The Precedent Is There

Large-scale philanthropic endowments are nothing new. In the past two decades:

- Michael Bloomberg has donated over $3.3 billion to his alma mater Johns Hopkins University.

- MacKenzie Scott has given away over $16 billion since 2019.

- The Gates Foundation operates with a $67 billion endowment and deploys billions annually to global health and education initiatives.

- Ken Griffin recently contributed $300 million to Harvard University.

Yet public broadcasting—a sector with tangible civic impact—has rarely drawn the same scale of contribution. This may be due in part to its status as a federal recipient, which gave the impression of permanence and stability. That illusion has now evaporated.

What remains is the opportunity to build a truly private-public media model—one whose operating capital is drawn from private wealth but whose editorial independence is legally insulated from donor interference.

A Corporate Response to a Public Crisis

Philanthropists are not the only entities positioned to act. Corporations, particularly those with vested interests in news, content, or public trust, have a strategic imperative to help capitalise such an endowment. Among the most obvious candidates:

- Technology firms such as Apple, Amazon, Google, and Meta, which dominate digital content distribution and advertising, but face persistent scrutiny over misinformation and platform responsibility.

- Media conglomerates such as Comcast, Disney, and Paramount, whose own news divisions benefit from a well-informed public and a credible informational ecosystem.

- Financial firms such as JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, and BlackRock, for whom geopolitical and social stability underpin long-term asset growth.

Indeed, a structured vehicle—such as a Public Broadcasting Endowment Corporation (PBEC)—could allow corporations to make long-term contributions that are tax-deductible, reputationally beneficial, and materially impactful. Their names need not appear on programming or editorial decisions; the return on investment would be brand credibility and a stronger civic framework.

Moreover, such a fund could become a flagship ESG initiative—aligning corporate interests with measurable civic outcomes.

Structuring the Capital Stack

A diversified funding approach would enhance resilience and buy-in. A potential framework:

| Donor Type | Target Contribution | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 275 HNWIs @ $100M | $27.5 billion | 100% |

| OR | ||

| 1,000 HNWIs @ $10M | $10 billion | 36% |

| 100 Corporates @ $100M | $10 billion | 36% |

| Broad-based campaign | $7.5 billion | 28% |

| Total | $27.5 billion | 100% |

A broad-based campaign could also complement elite contributions. Imagine a national “Democracy Dividend” campaign: one million Americans pledging $1,000 annually for ten years. That alone would yield $10 billion—a testament to public commitment alongside private wealth.

From Pledge Drives to Private Equity

Public broadcasting has traditionally raised funds through grassroots donations and corporate underwriting. But this model is no longer viable on its own. What is required is a transition from pledge drives to portfolio management.

The envisioned endowment would be governed by a professional board and investment committee, structured similarly to major university endowments. Earnings would be deployed annually to:

- Sustain local PBS and NPR affiliates, especially in underserved areas

- Support original investigative journalism and children’s educational content

- Fund innovation in digital and streaming public media

- Preserve and digitize historic programming archives

- Maintain emergency broadcast systems and rural information networks

Crucially, editorial integrity would be enshrined by legal charter—preventing donors or sponsors from influencing content.

Philanthropy as Infrastructure

Too often, philanthropy is reactive—applied to symptoms rather than systems. An endowment, by contrast, is structural. It is a recognition that certain institutions are too important to be left at the mercy of annual budgets, market swings, or election cycles.

The erosion of federal support for public broadcasting is a warning signal. The infrastructure of civic life—fact-based journalism, educational programming, and communal storytelling—requires capital insulation, not just ideological support.

This is not about saving Big Bird or Masterpiece Theatre. It is about fortifying one of the last remaining platforms where Americans—regardless of political identity or geography—encounter one another not as algorithms or enemies, but as citizens.

Will the Wealthy Step Up?

The government has walked away. The funding gap is real. But the wealth to close it is readily available.

If even a fraction of the world’s wealthiest individuals and corporations stepped forward with capital rather than condolences, the future of public broadcasting could shift from a question of survival to a model of strategic, sovereign independence.

In the end, it is not about whether we can raise $27.5 billion. It is whether the people most capable of doing so will finally recognise that their wealth is not a wall—but a bridge to a more stable, informed, and democratic society.

🎯 Key Facts

- Total CPB federal subsidy rescinded: $1.1 billion

- This funding supports both PBS and NPR, primarily by supporting local member stations.

- Goal: Replace $1.1 billion per year in perpetuity through investment returns from an endowment.

📊 Endowment Calculation Assumptions

To generate $1.1 billion annually, the endowment must safely yield that amount without depleting principal.

| Scenario | Investment Return | Annual Draw Rate | Required Endowment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | 5% return | 4% draw | $27.5 billion |

| Moderate | 6% return | 4% draw | $27.5 billion |

| Ambitious | 8% return | 5% draw | $22 billion |

Rule of Thumb:

- Endowment needed = Annual Budget ÷ Draw Rate

- So for $1.1 billion with a 4% draw:

$1,100,000,000 ÷ 0.04 = $27.5 billion

🏛️ Comparisons to Similar Institutions

| Institution | Endowment | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Harvard University | $50.7B (2024) | Largest university endowment |

| Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation | $67B (2024) | Largest U.S. philanthropic fund |

| NPR | N/A | Does not have a large central endowment |

| Howard University | $1B (2024) | Largest HBCU endowment |

🔄 Alternatives or Supplements

If not a full endowment, partial coverage models could include:

- A $5B–$10B endowment paired with annual fundraising

- Public-private consortiums involving universities, foundations, and philanthropists

💡 Final Recommendation

To fully replace the $1.1B annual CPB subsidy, a minimum $27.5 billion endowment would be needed under conservative investment assumptions.

This figure ensures long-term sustainability without needing annual appropriations or political reauthorization.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.