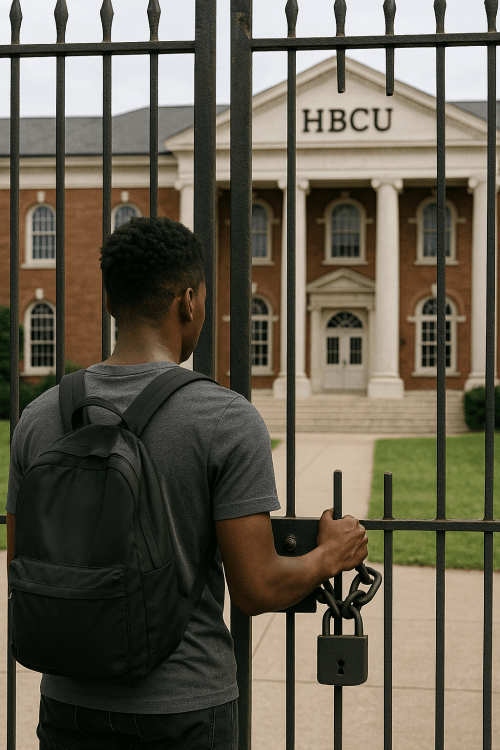

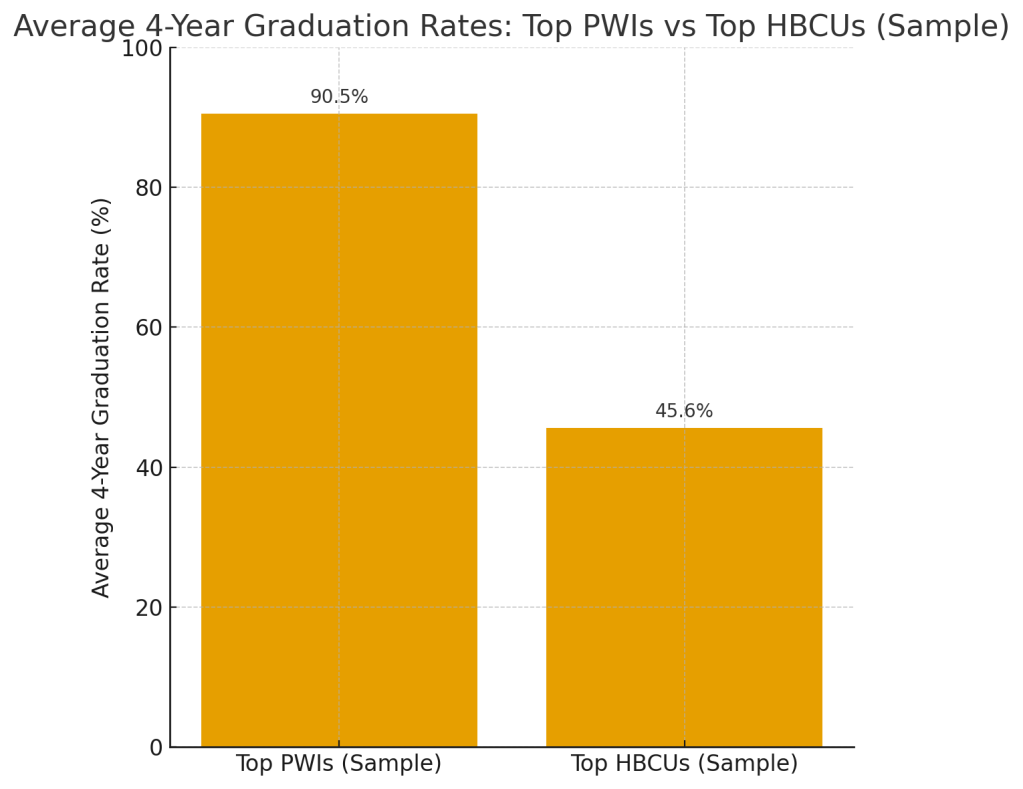

The four-year graduation rate is often presented as a benign statistic tucked inside higher education reports, but for institutions serving African America, it is not benign at all. It is the lever on which long-term wealth, institutional survival, and multigenerational stability subtly depend. Wealthy universities treat the four-year graduation rate not as an outcome but as an engineered product, backed by endowment might, operational discipline, and capital-rich ecosystems. Their students finish on time because the institution ensures they are shielded from interruption. Meanwhile, HBCUs navigate a different reality: the same students who possess the intellectual capacity to thrive are too often delayed not by academics but by the economic turbulence that disproportionately defines their journey. It is here between the idea of talent and the machinery of capital that the four-year graduation rate becomes a revealing measure of African America’s structural position in the American economic hierarchy.

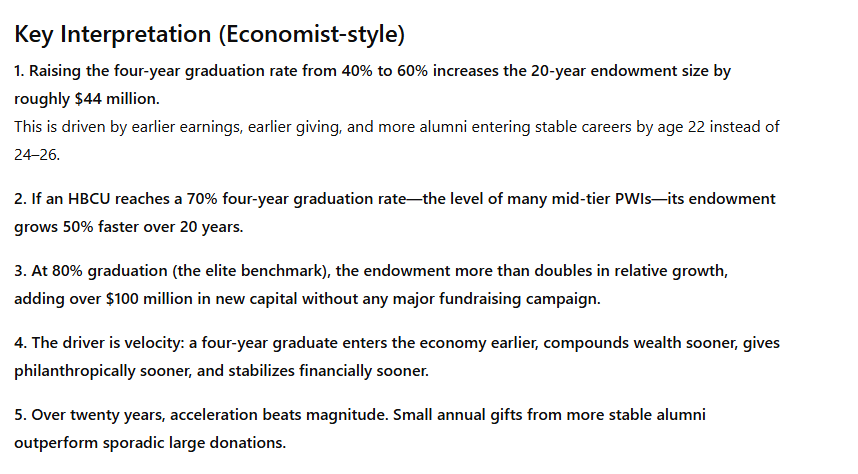

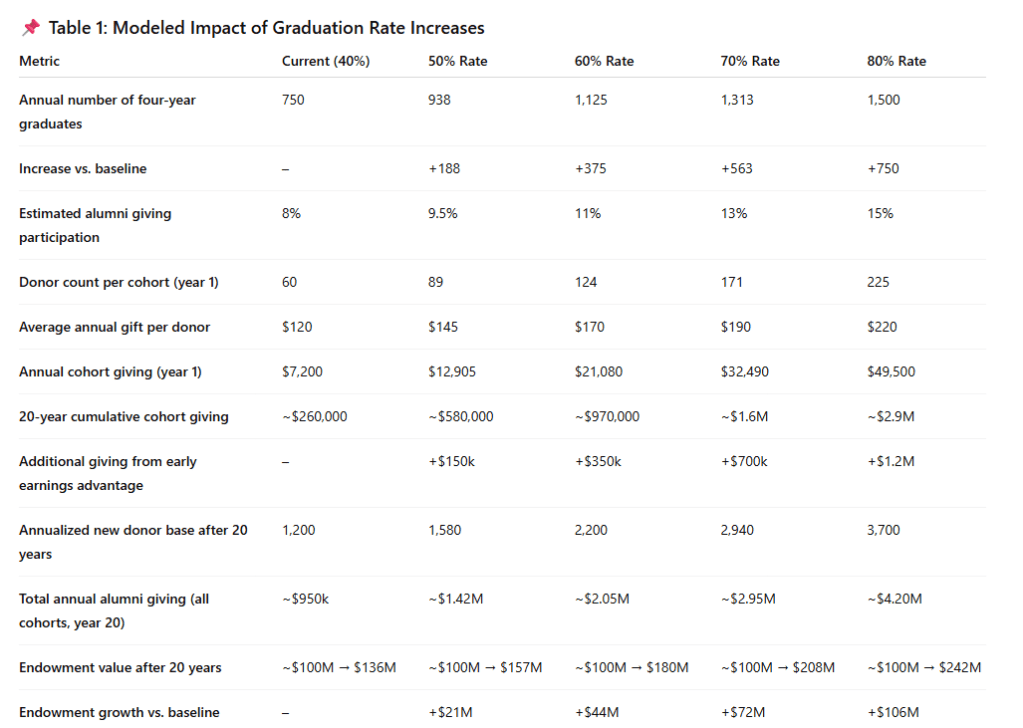

A delayed degree carries a cost structure that compounds aggressively. Extra semesters are not simply tuition bills; they are opportunity-cost accelerants. A student who graduates at 22 enters the workforce two to three years ahead of a peer who reaches the finish line at 24 or 25. Those early earnings fund retirement accounts earlier, compound longer, support earlier homeownership, and create the financial runway that future philanthropy relies upon. For African American students who statistically begin college with fewer financial reserves and exit with higher student debt those lost years are wealth years. They represent not only diminished individual prosperity but the slowed creation of a donor class that HBCUs and other African American institutions depend on to build endowment strength and institutional sovereignty.

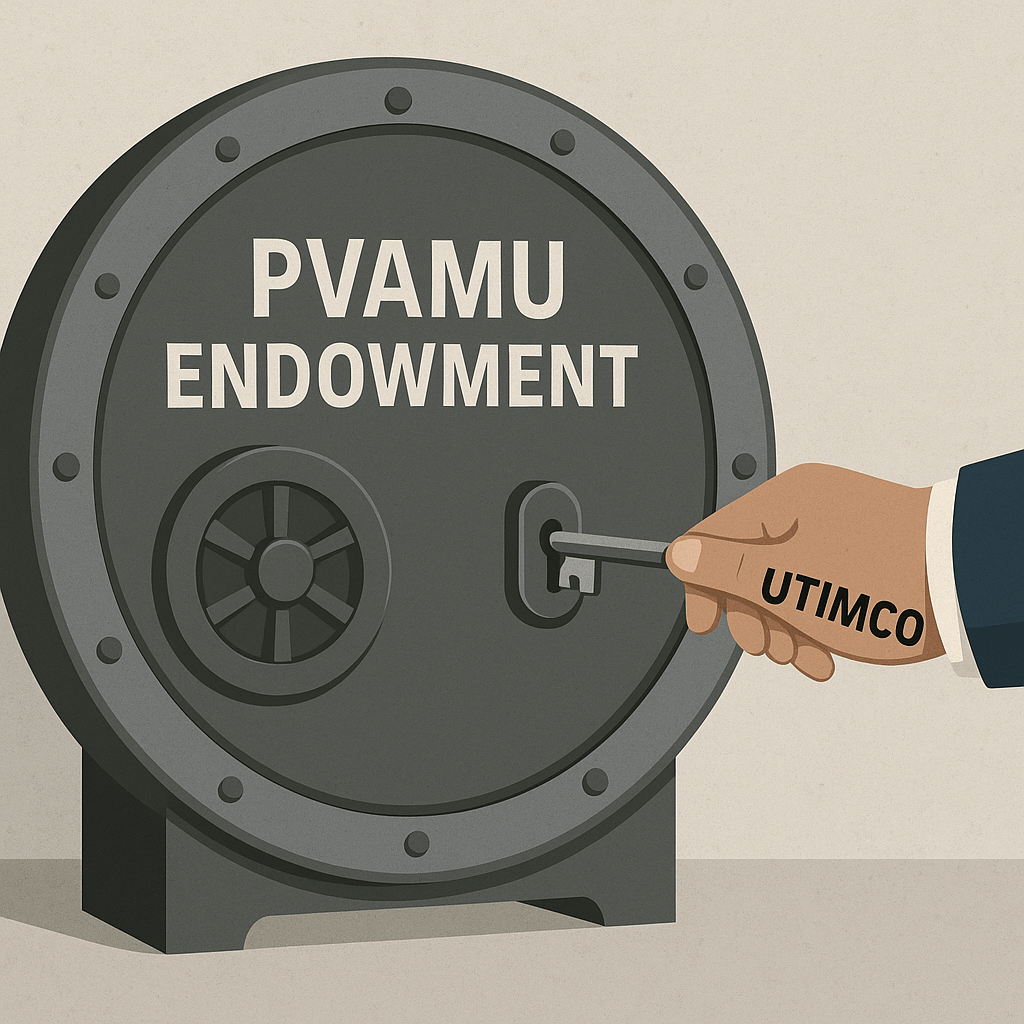

Endowments, which serve as the economic lungs of a university, breathe differently depending on how quickly their alumni progress into stable earning years. A university that graduates students in four years rather than six gains an alumni base that stabilizes earlier, saves earlier, invests earlier, and gives earlier. A philanthropic ecosystem is essentially a long-term consequence of time management: the more years an alumnus spends debt-free and employed, the more predictable their giving pattern becomes. Elite institutions leverage this fact elegantly. HBCUs, despite producing extraordinary alumni under significantly harsher financial conditions, remain constrained by the delayed timelines imposed by student financial fragility.

Financial fragility is a central explanatory variable in the HBCU graduation gap. It is not uncommon for a student to miss a semester because of a $300 balance or a transportation breakdown that derails their schedule. In the broader American economic system, such modest shocks rarely jeopardize a wealthy student’s trajectory. But within the HBCU ecosystem, they represent the sharp edges of institutional undercapitalization meeting the exposed nerves of household vulnerability. The four-year graduation rate is therefore not simply a metric of academic navigation but a map of where the Black household economy intersects with American higher education’s structural inequities.

This makes alumni involvement not a sentimental tradition but an economic necessity. Alumni can narrow the financial fragility gap more efficiently than any other stakeholder group. Microgrant funds, even modestly capitalized, are capable of eliminating the most common disruptions that extend time-to-degree. A $250 emergency grant can protect $25,000 in long-term student debt. A $500 intervention can guard a student’s four-year trajectory and thus preserve two additional years of post-graduation earnings that ultimately benefit both the graduate and the institution’s future endowment. Alumni-funded tutoring, advising enhancements, STEM support programmes, and paid internships create artificial endowment-like effects: stabilizing student progression even when the institutional endowment itself is undersized.

Yet HBCU alumni cannot focus solely on the university years if the goal is a structurally higher four-year graduation rate. The process begins far earlier within K–12 systems that shape academic readiness long before students set foot on campus. The elite institutions that boast 85–95 percent on-time graduation rates are drawing from K–12 ecosystems with intense capital saturation: high-quality teachers, advanced coursework, stable households, well-funded enrichment programmes, and neighborhoods that function as multipliers of academic preparedness. HBCU alumni have an opportunity to influence this pipeline through investments that are often modest in individual scope but transformational in aggregate impact. Funding reading centres, coding clubs, college-prep academies, robotics labs, literacy coaches, and after-school tutoring programmes plants the seeds of future four-year graduates years before college entry.

Indeed, a strong K–12 foundation reduces the need for remedial coursework, accelerates major declaration, strengthens performance in gateway courses like calculus and biology, and diminishes the likelihood that students need extra semesters to satisfy graduation requirements. When alumni support dual-enrollment initiatives, sponsor early-college programmes, or build partnerships between HBCUs and local school districts, they enlarge the pool of college-ready students whose likelihood of completing on time is structurally higher. In this sense, investing in K–12 is not philanthropy it is pre-endowment development.

The economic implications of strengthening both ends of the education pipeline are enormous. A 20–30 percentage-point improvement in four-year completion rates across the HBCU ecosystem would reduce student loan debt burdens by billions, accelerate African American household wealth accumulation, raise the number of alumni earning six-figure incomes before age 30, and increase the philanthropic participation rate across Black institutions. Over decades, such shifts ripple outward: stronger alumni lead to stronger HBCUs, which lead to stronger civic, cultural, and economic institutions in African American communities, which themselves create more stable families, more prepared K–12 students, and more future college graduates. The system feeds itself when time is efficiently managed.

In the HBCU Money worldview, where institutional power is the only reliable safeguard against structural marginalization, time-to-degree represents one of the clearest and most overlooked levers of collective economic advancement. In a Financial Times context, the four-year graduation rate appears as a liquidity indicator—showing how quickly an institution converts educational investment into economic output. In The Economist’s framing, it reveals the mismatched capital structures between wealthy universities and historically underfunded ones, and how those mismatches reproduce inequality in slow, quiet, compounding increments.

For African America, the conclusion is unmistakable. The four-year graduation rate is not merely a statistic. It is a wealth mechanism. It is an endowment accelerator. It is an institutional survival tool. And it is a community-level economic strategy that begins in kindergarten and culminates with a diploma. If HBCU alumni wish to see their institutions strengthen, their communities accumulate wealth, and their young people enter the economy with maximum velocity, then they must make both K–12 investment and four-year graduation obsession-level priorities. Institutions rise with the financial stability of their graduates. Ensuring those graduates complete degrees on time is one of the most effective—and least discussed—strategies available for building African American institutional power across generations.

A Tale of Two Virginias:

A revealing contrast in American higher education can be observed by examining two institutions that sit just 120 miles apart: Virginia State University (VSU) and the University of Virginia (UVA). NACUBO estimates VSU’s endowment at approximately $100 million for around 5,000 students, producing an endowment-per-student of roughly $20,000. According to U.S. News, VSU graduates 27% of its students in four years. UVA, one of the most heavily capitalized public universities in the world, possesses an endowment of roughly $10.2 billion for about 25,000 students, an endowment-per-student of approximately $410,000, more than twenty times the capital density VSU can deploy. Its four-year graduation rate stands at 92%.

The gulf between the two institutions reflects not a difference in student talent but a difference in institutional resource density and shock absorption capacity. A VSU student must personally carry far more academic and financial fragility. A single $300 expense can knock them off their semester plan. A delayed prerequisite can add a year to their degree. Limited advising bandwidth means problems are often discovered only after they have already extended time-to-degree. UVA faces the same categories of issues, but its endowment, staffing, and operating budgets act as buffers absorbing shocks before they disrupt academic progress.

Endowment-per-student, therefore, is not merely a balance-sheet statistic; it is a proxy for how much risk the institution can carry on behalf of its students. UVA carries most of the risk. VSU students carry most of their own. UVA’s 92% four-year graduation rate is a reflection of institutional cushioning. VSU’s 27% rate reflects its absence.

Yet to understand the true economic cost of the graduation gap, it is useful to model what would happen if VSU improved its four-year graduation rate—first to a plausible mid-term target such as 50%, and then to a UVA-like 90%. Both scenarios dramatically change the trajectory of the institution.

Assume that VSU today produces roughly 1,350 graduates every four years (based on a 27% rate). If it increased its four-year graduation rate to 50%, VSU would instead graduate 2,500 students every four years, an increase of 1,150 additional on-time graduates, each entering the workforce two years earlier, with lower student debt, earlier retirement contributions, earlier homeownership, and earlier philanthropic capacity. Even if only a modest fraction of these additional graduates contributed $50–$150 annually to VSU’s endowment, the compounding effect across 20 years would be substantial. Under conservative assumptions with basic donor participation growth and average returns of 7% VSU’s endowment could plausibly grow from $100 million to $155–$170 million over two decades, powered largely by the increased velocity and increased number of earning alumni.

Now consider the UVA-like scenario. A four-year graduation rate of 90% at VSU would mean roughly 4,500 on-time graduates every four years or over three times the current output. This scale of early, debt-lighter graduates would fundamentally transform VSU’s financial ecosystem. Even minimal alumni participation say, 12–15% giving $100–$200 annually would translate into millions in annual recurring contributions. Over two decades, with investment returns compounding, VSU’s endowment could grow not to $150 million but potentially to $300–$400 million, depending on participation rates and gift sizes. That would triple the institution’s financial capacity without a single major donor campaign, capital campaign, or extraordinary windfall. The key variable is simply graduation velocity.

This comparison illustrates a broader truth: endowment growth is not just a function of investment strategy but of how quickly a university converts students into earning alumni. A student who graduates at 22 gives for 40–50 years. A student who graduates at 25 gives for 30–35 years. A student who drops out does not give at all. VSU’s current 27% four-year graduation rate is not merely an academic statistic—it is an endowment drag factor. UVA’s 92% rate is an endowment accelerant.

The financial distance between the two universities appears vast, but it is governed by a formula that HBCUs can influence: more on-time graduates → more early earners → more consistent donors → more endowment growth → more institutional cushioning → more on-time graduates. VSU today sits at the fragile end of this cycle. A graduation-rate increase to 50% would move it into a position of stability. A leap to 90% would place it into an entirely different institutional category—one where it begins to accumulate capital in the same compounding manner that allows institutions like UVA to weather downturns, attract top faculty, and protect students from the shocks that so often derail academic momentum.

VSU cannot replicate UVA’s wealth in the short term. But by increasing on-time graduation, it can replicate the mechanism through which wealthy universities become wealthier. And that mechanism—graduation velocity—is one of the few levers fully within reach of alumni, leadership, and institutional partners.

Here are four strategic, high-impact actions HBCU alumni associations or chapters can take to directly raise four-year graduation rates and strengthen institutional wealth:

1. Create a Permanent Emergency Microgrant Fund (The “$300 Fund”)

Most delays in graduation arise from small financial shocks:

balances under $500, transportation failures, book costs, or housing gaps.

Alumni chapters can formalize a permanent, locally governed microgrant fund offering rapid-response support (48–72 hours).

A chapter raising just $25,000 per year can prevent dozens of delays, each shielding students from additional semesters of debt and protecting the institution’s future alumni giving pipeline.

This is low-cost, high-yield institutional intervention.

2. Fund Paid Internships and Alumni-Mentored Work Opportunities

Students who work long hours off campus are more likely to fall behind academically, switch majors repeatedly, or extend enrollment.

Alumni chapters can create paid internships, stipends, or alumni-hosted part-time roles tied directly to students’ majors.

Each position:

- reduces the student’s financial burden

- keeps them academically aligned

- accelerates pathways to stable post-graduate employment

This lifts graduation rates and increases alumni earnings—expanding the future donor base.

3. Build K–12 Pipelines in Local Cities That Feed Directly Into HBCUs

Four-year graduation begins long before freshman year.

Alumni chapters can adopt 2–3 local schools and support:

- literacy acceleration programs

- SAT/ACT prep

- dual enrollment partnerships

- STEM and robotics clubs

- early-college summer institutes hosted by their own HBCUs

Better-prepared students require fewer remedial courses, retain majors longer, and graduate on schedule, raising institutional performance and future endowment sustainability.

This is pre-investment in the future alumni base.

4. Pay for Summer Courses After Freshmen Year to Build Early Credit Momentum

After their first year, many students fall off the four-year pace due to light credit loads, failed gateway courses, or sequencing issues that a single summer class could easily correct. Yet for many HBCU students, summer tuition—often just one or two courses—is financially out of reach.

Alumni chapters can establish a Freshman Summer Acceleration Grant to pay for up to two summer course immediately after freshman year, allowing students to:

close early credit gaps,

retake or accelerate critical prerequisites,

reduce future semester overloads,

create a credit cushion for unexpected disruptions,

stay aligned with four-year degree maps.

A small investment of summer tuition produces an outsized institutional return: students enter sophomore year on pace, avoid bottlenecks in upper-level coursework, and dramatically increase their likelihood of graduating in four years. This is an early-stage compounding effect—protecting momentum before delays become expensive and permanent.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.