By William A. Foster, IV

“When hypocrisy is a character trait, it also affects one’s thinking, because it consists in the negation of all the aspects of reality that one finds disagreeable, irrational or repugnant.” – Octavio Paz

My freshman year of high school was nerve wracking and exciting. As far as academics were concerned I did fairly well that first year, but the football field was where I was most excited. I had a good year and heard rumblings that the varsity head coach had me in consideration for varsity my coming sophomore year. I fit his system of defense. I was small, but I had good football IQ and did not mind taking or giving a hit. All of that changed though when he got fired at the end of my freshman year for using an ineligible player during the year and having to forfeit almost all of the school’s games. In his place came a coach I was familiar with because the year before me and father went to see Jack Yates High School, the high school I grew up watching my father coach play in the state playoffs take on Temple High School and the offensive coordinator would then become our school’s head coach. I was excited, but nervous. They ran a different brand of football. We had been a predominantly running team and our talent fit that style. Instead, he ran an early version of the spread that was not very popular throughout. We were built for ground and pound and he wanted an air attack. I was switched positions from defense to offense and scored the first touchdown of the new regime, and from there it was all down hill.

By my junior year, I was deep into my academics and this was becoming a problem unbeknownst to me for my coaches. It would come to a head when I asked for more time before practice to get tutoring and one of my coaches said to me, “Son, you need to choose between them books and this team.” I would never forget that moment. I was shocked. I had parents who were college professors. Choose? Is he serious? Not only was he, but it would escalate. After our game that week, which I did not have a particularly good one and little did I know it was really the end of my football career. As we sat and watched game film the next week a play that I missed came up. The coach stopped the film, flipped on the lights, and looked dead at me and said to the team, “We have some players who are not committed to this team.” Being the hot tempered teenager I was at the time, I calmly put my head down as if I was rubbing it with one finger. I will let you guess which one. From that point on, I was in the dog house and at the end of the season was told to turn my equipment in. My father would talk me back onto the team for my senior year, but quite honestly it was hell and part of me wish I had never gone through it. I loved football growing up, playing in the street, watching my father coach, going to the state championship, and thought one day that would be me. Little did I understand, the “business” I was walking into.

Texas high school football is different. There is no doubt about that and Friday NIght Lights probably left more than a few things out that would traumatize people. I for one recall getting pulled over one night after drinking and in no condition to be behind a wheel, but once the police found out I played for the local high school team they were more interested in telling me about them playing for the police football team. Ultimately, they let me go with a minor in possession and let me drive myself home. On my high school football team we had some of everything going on from the drug dealers, drug users, massive illiteracy, and more than a few things I have blocked from my memory for good reason.

You see most of them were not just playing football for the love of the game. They were playing because they saw it as their only way out. Many of my teammates came from impoverished backgrounds, with few educational opportunities and even fewer economic ones. For them, football was not just a pastime it was a potential career. And yet, despite the immense pressure placed on high school athletes to perform, there is virtually no financial compensation for their efforts. If we are going to argue that college athletes deserve to be paid for their labor, then high school athletes who also generate millions of dollars in revenue deserve the same consideration.

The financial power of high school football, especially in states like Texas, is undeniable. According to a 2019 report by the Texas Education Agency, the state spent over $500 million on high school football stadiums between 2008 and 2018. Some stadiums rival those of small colleges in both size and amenities, with the most expensive high school stadium in the country, Legacy Stadium in Katy, Texas costing $72 million to build. These stadiums are packed on Friday nights, bringing in millions of dollars in ticket sales, sponsorships, and media rights.

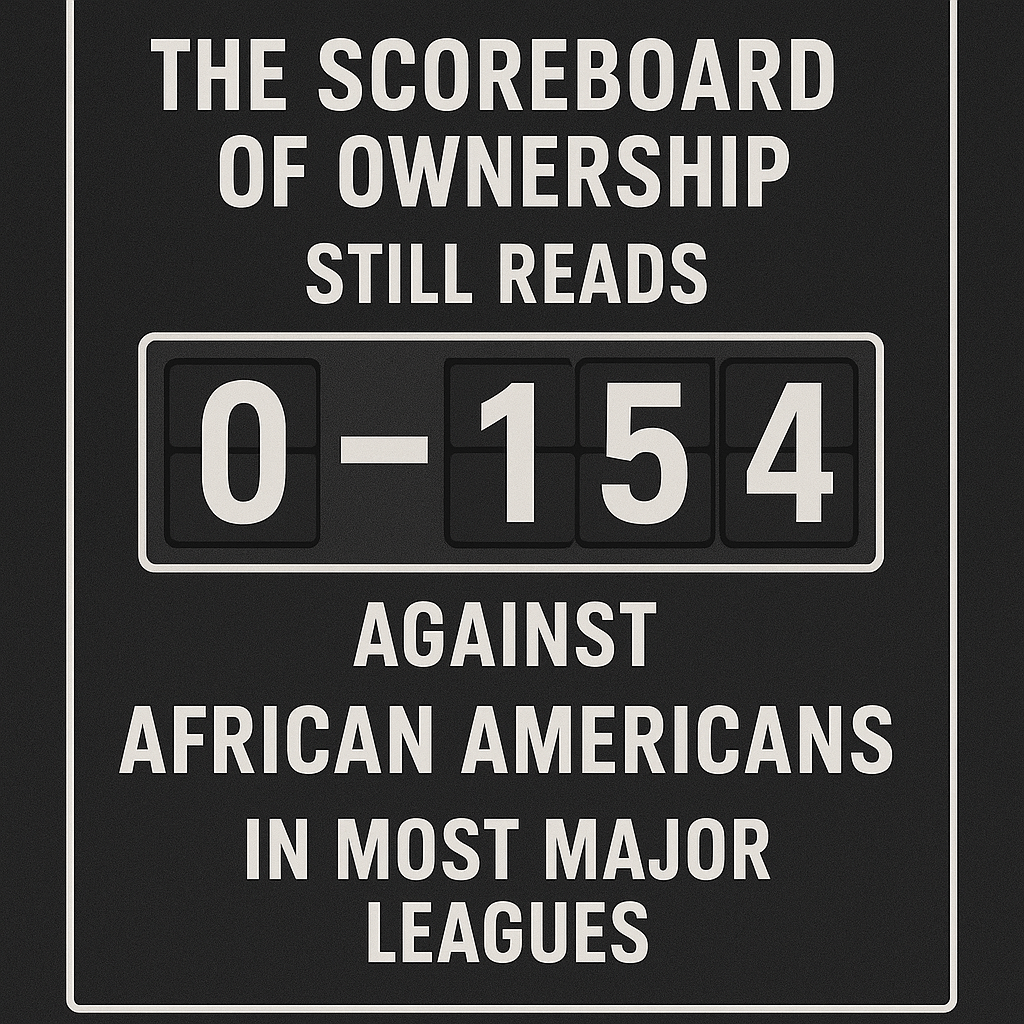

Despite this, the players on the field, the ones drawing the crowds see none of this revenue. While their coaches earn six-figure salaries (the highest-paid high school coach in Texas makes $158,000 per year), the athletes themselves play for free, risking injury and sacrificing their time and education in the hopes of making it to the next level.

The physical toll on high school athletes is just as severe as it is for college players. According to a study by the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS), there are approximately 1.1 million high school football players in the U.S., and every year, an estimated 300,000 sports-related concussions occur among high school athletes. The risk of serious, long-term injury is real, yet these players receive no compensation for putting their bodies on the line.

Consider this: the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) has been pressured to provide financial assistance for athletes suffering from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a brain disease caused by repeated head trauma. If college athletes deserve compensation for these risks, shouldn’t high school athletes who are just as vulnerable also receive financial protection?

Some may argue that high school sports do not generate as much money as college athletics. While it is true that high schools do not have billion-dollar TV contracts like the NCAA, local revenue generation is still significant. The Texas University Interscholastic League (UIL) collects millions of dollars in revenue from the state football championships, including ticket sales, sponsorships, and broadcasting rights. ESPN, Fox Sports, and other major networks regularly feature high school games, and Nike and Adidas have begun sponsoring elite high school programs.

In 2021, Alabama’s Hoover High School reported earning over $2 million annually from its football program. Southlake Carroll High School in Texas made nearly $1.5 million in a single season from ticket sales, donations, and sponsorships. The bottom line? High school football is not just a game it is a business. And in any other business, the labor force gets paid.

The NCAA’s decision to allow Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) deals for college athletes has already set a precedent. High school athletes in several states including Texas, California, and Florida are now allowed to profit from their NIL rights. Players like Jaden Rashada, a high school quarterback in California, reportedly signed a $9.5 million NIL deal before ever playing a college snap. This demonstrates that high school athletes do, in fact, have market value.

But what about the majority of players who will never receive NIL deals? They are still sacrificing their time, bodies, and educational opportunities for the sport. If coaches, administrators, and organizations profit from their efforts, then why should the athletes themselves be excluded? A stipend, medical coverage, or even a trust fund for players who complete their high school careers would be a step in the right direction.

Critics argue that paying high school athletes could open the door to corruption, recruiting scandals, and financial mismanagement. However, these problems already exist in amateur sports. Boosters have been caught illegally paying recruits for decades, and schools have been sanctioned for bending the rules to secure top talent. If anything, formalizing a compensation structure would bring transparency to a system that already operates in the shadows.

Others worry about the financial burden on school districts. However, if schools can afford multi-million-dollar stadiums and six-figure coaching salaries, then they can find ways to fairly compensate athletes. The money is already there but the question is who gets to benefit from it.

The reality is that high school football is more than just a game. It is an industry, one that generates millions of dollars while placing tremendous physical and mental demands on young athletes. If we accept the argument that college athletes should be paid because of the revenue they generate, then we must apply that same logic to high school athletes.

High school athletes do more than just entertain. They fill stadiums, drive merchandise sales, and fuel an economy that benefits everyone except them. It is time to acknowledge their worth and compensate them accordingly. Whether through stipends, medical coverage, or NIL opportunities, high school athletes deserve to see a share of the wealth they help create. Otherwise, we continue to exploit their labor under the guise of “amateurism.” The system is broken, and until high school athletes get a piece of the pie, it will remain unfairly rigged against them.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.