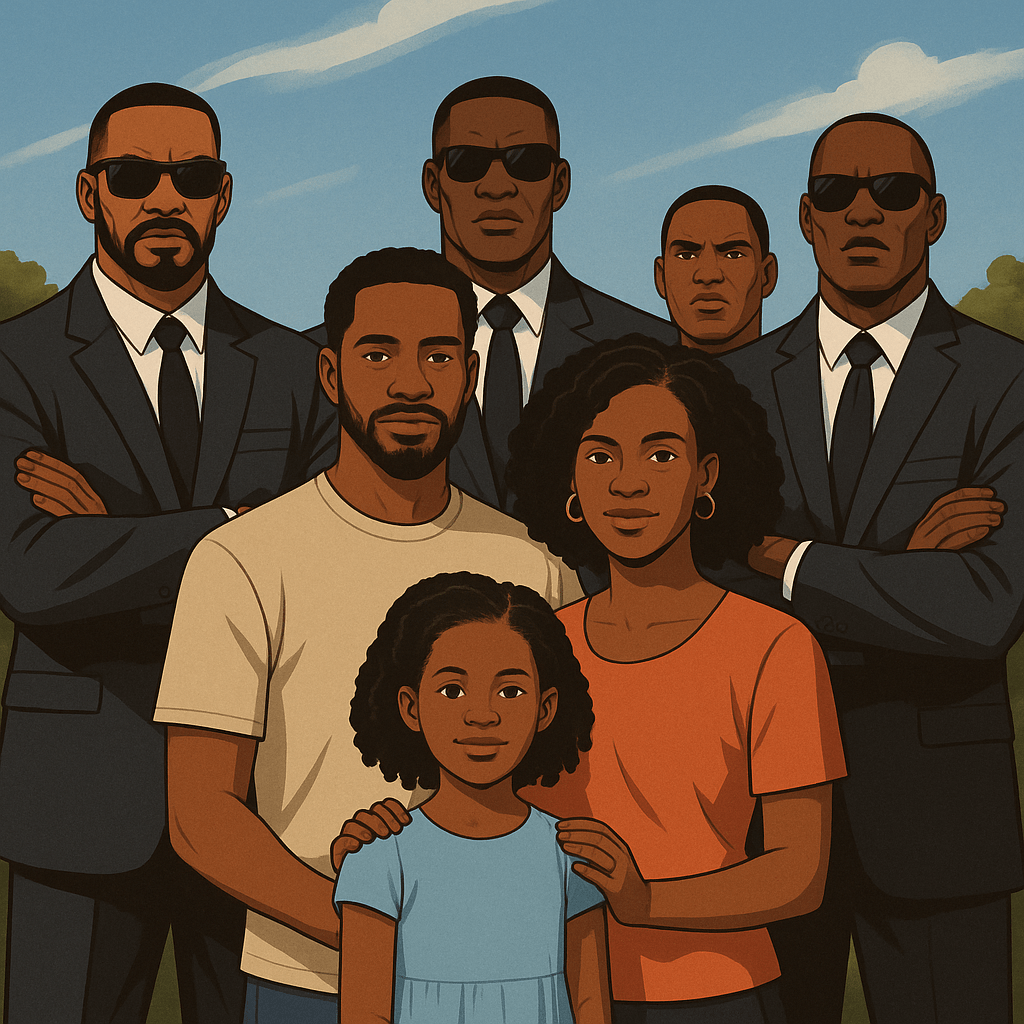

“The nice thing about teamwork is that you always have others on your side.” – Margaret Carty

The majority of how people make financial decisions both big and small is often with the best of intentions, but as most of us know, that is also where the road to hell was paved.

In the realm of personal finance, intentions without information can be dangerous. Every day, millions make financial decisions that shape their futures from picking a credit card, accepting a student loan, buying a car, or investing in a 401(k). Yet, especially within African American households, these decisions are frequently made with limited knowledge, access, or trusted advisors. Generational poverty, systemic exclusion, and inconsistent education have all contributed to a reality where financial literacy remains low, and bad financial advice can sometimes pass for tradition.

The statistics are sobering: According to a 2022 FINRA study, only 34% of African Americans could correctly answer four out of five basic financial literacy questions, compared to 55% of whites. This gap is more than academic it’s economic. Financial illiteracy compounds over time. It creates debt spirals, stifles homeownership, delays retirement planning, and weakens intergenerational wealth transfers. It also helps explain why the median Black household wealth remains only a fraction of that of white households.

So, if you’re navigating this landscape, how do you get the advice you need especially when your circle may not have the right information either?

Let’s explore how to build a financial circle of influence and more importantly, how to choose the right voices to include.

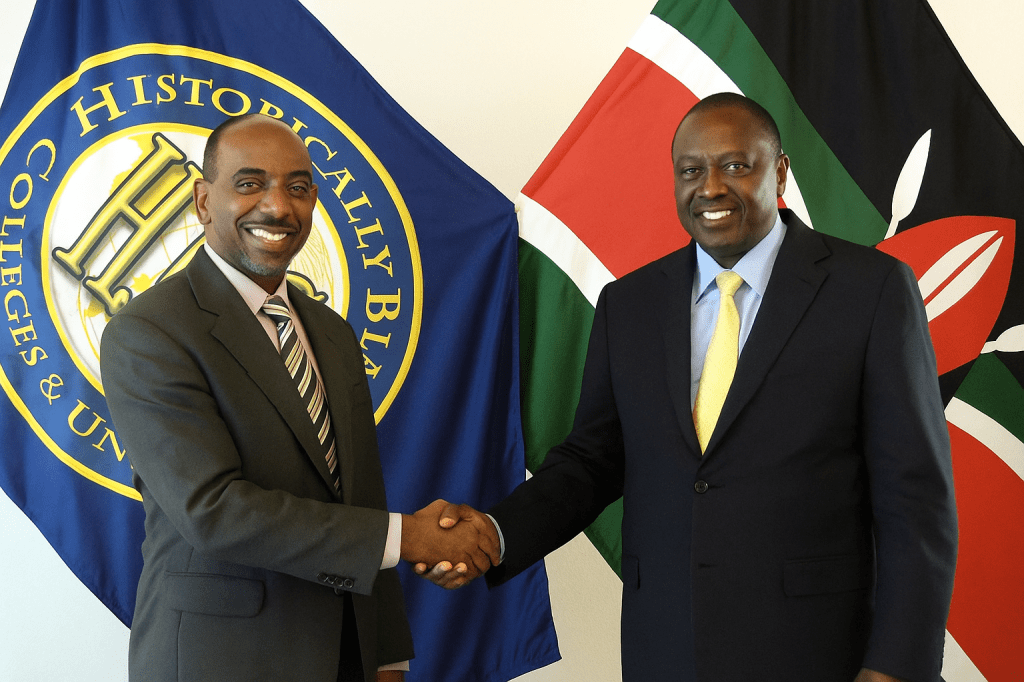

In far too many cases, personal finance education starts after the mistakes are made such as missed student loan payments, wrecked credit scores, or maxed-out credit cards. Even institutions designed to uplift like Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) have been slow to require financial literacy as a foundational component of their curricula.

Imagine if every incoming freshman at an HBCU were required to complete a month-long intensive in budgeting, credit, and financial aid before stepping foot on campus. Not only that, but if financial education were embedded into their collegiate journey; customized to their majors, infused with real-world applications, and rooted in African American economic history and philanthropy the results could be transformative. Courses in credit management, entrepreneurship within your field, the basics of investing, and even African American economic institutions (from mutual aid societies to credit unions) could help create a generation that thinks differently and acts differently about money. Until that infrastructure exists consistently, however, students and families are often left to fend for themselves, relying on informal networks, questionable online advice, or predatory “wealth influencers.” That’s why building your own financial circle is more important than ever.

Your financial circle isn’t just about having a stock tip group chat. It’s your personal advisory board: a small group of 3 to 5 people you trust to help you make decisions ranging from the everyday to the existential.

Think of them as your informal “board of directors.” You don’t need them to be millionaires or financial advisors (though one or two wouldn’t hurt). But you do need them to be:

- Financially aware: They have a basic grasp of sound financial practices.

- Ethical: They’re not trying to sell you anything or exploit your trust.

- Supportive: They understand your goals and will offer guidance in your best interest, not theirs.

- Diverse in expertise: Ideally, each brings a different angle—entrepreneurship, investing, real estate, credit, budgeting, etc.

The value in this diversity is simple: no one person has all the answers. An investor might advise risk, while a credit specialist might urge caution. You need to weigh both perspectives to make the right decision for you.

Who Belongs in Your Circle?

There are five archetypes worth considering:

1. The Budget Master

This person might not have flashy investments or a six-figure salary, but they manage what they have with laser precision. They know how to stretch a dollar, pay off debt, and stick to a plan. They understand discipline and sacrifice—essential traits in building wealth, not just income.

Why you need them: For insight into monthly budgeting, avoiding lifestyle creep, and making responsible day-to-day decisions.

2. The Wealth Builder

This is your investor friend. Maybe they dabble in the stock market, own real estate, or have a retirement plan that’s growing nicely. They’ve made mistakes, but they’ve learned from them and they’re willing to share.

Why you need them: They help you think long-term. They understand compound interest, asset allocation, and the psychology of investing.

3. The Entrepreneur

Whether it’s a side hustle or a full-time enterprise, this person knows what it means to take calculated risks. They can offer insight into taxes, business credit, scaling a company, or diversifying income streams.

Why you need them: Because job security is not what it used to be and entrepreneurial skills are often the key to economic mobility.

4. The Credit Whisperer

This person has mastered the FICO system, understands debt instruments, and knows how to use credit to their advantage. They’re also likely well-versed in financial regulations and tools like balance transfers, refinancing, and consolidation.

Why you need them: To help you avoid common traps and use credit as a tool, not a trap.

5. The Cultural Capitalist

This person is grounded in the historical and cultural aspects of Black economic life. They can talk about Black Wall Street, the role of Black banks, and how to give back without going broke. They remind you that financial decisions aren’t just about you—they’re about us.

Why you need them: To stay grounded in your values and understand how your success contributes to a broader community legacy.

How to Choose the Right People

The first step to building a financial circle is intentionality. Here are a few principles:

1. Don’t Confuse Proximity with Expertise

Just because someone is family or close doesn’t mean they’re qualified to advise you. Seek out people who have demonstrated results such as consistent savings, strong credit, a stable business not just opinions.

2. Look Beyond Titles

A financial advisor with a fancy office isn’t necessarily better than your aunt who retired early on a teacher’s pension. The best advisors aren’t always licensed—they’re often experienced, candid, and care about your outcomes.

3. Vet for Integrity

Before you invite someone into your financial circle, ask: Are they selling me something? Are they pushing an agenda? Can I trust them to tell me the truth—even when it’s uncomfortable?

4. Value Perspective over Perfection

Your circle doesn’t have to be made up of financial rockstars. It has to be honest, dependable, and thoughtful. Sometimes the best advice comes from someone who made a mistake and is willing to share the lesson.

Here are a few places to start identifying people for your financial circle:

- Community and alumni networks (especially HBCU alumni groups)

- Professional associations (Black MBA, Black CPA organizations)

- Libraries (many now offer financial literacy sections)

- Local credit unions and Black-owned banks (many host workshops or financial education seminars)

And yes, if you can afford one, a certified financial planner (CFP) can be a game-changer. But even that relationship should be approached with due diligence and comparison—interview multiple advisors, ask for their fiduciary status, and never be afraid to walk away if the fit doesn’t feel right. Verify an individuals’s CFP certification and background at https://www.cfp.net/verify-a-cfp-professional.

Until institutions mandate courses, you’ll have to become your own professor. Here’s a four-year self-guided plan:

| Year | Topics | Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | Budgeting & Credit Basics | Your Money or Your Life, NerdWallet, Experian Boost |

| Year 2 | Investing 101 | The Simple Path to Wealth, Morningstar, Robinhood Learn, Bogleheads |

| Year 3 | Entrepreneurship | The Lean Startup, SBA.gov, Score Mentors |

| Year 4 | Philanthropy & Estate Planning | Decolonizing Wealth by Edgar Villanueva, NAACP Legacy Programs |

Add to that regular podcasts (The Economist, Financial Times), YouTube channels (like Minority Mindset), and community financial challenges (like savings goals, no-spend months, or stock clubs), and you’ll be ahead of the curve.

There’s a subtle but powerful difference between advice and empowerment. Advice tells you what to do. Empowerment teaches you how to think.

Your financial circle should do both but lean into the latter. The best financial guidance is that which helps you ask better questions, weigh competing options, and make decisions aligned with your values and goals.

Ultimately, the journey to financial health isn’t just about tools, apps, or strategies—it’s about relationships. And the most important one is the one you build with your future self.

So, who helps you with personal finance decisions? The better question might be: Who will you invite to help you get where you want to go?

Choose wisely.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.