“If you want to know how people are doing, then look at the institutions that serve them. For better or worse.” – William A. Foster, IV

The commercialization of everything has not simply weakened communities it has restructured the way people relate to each other, to time, and to the idea of a shared life. America once reserved certain days as collective pauses: Thanksgiving as a family gathering, Christmas and New Year’s as moments of reconnection, and Sundays as a weekly restoration ritual. Those pauses were essential to the glue of community. But as corporations learned how to monetize nearly every aspect of human behavior, they also learned how to monetize time. And once time is monetized, community becomes negotiable. The result is a society where the day after Thanksgiving is more about shopping than family, where Sundays revolve around televised commercial events instead of rest, and where companies treat holidays not as protected communal moments but as logistical inconveniences that employees must navigate by sacrificing their own paid-time-off.

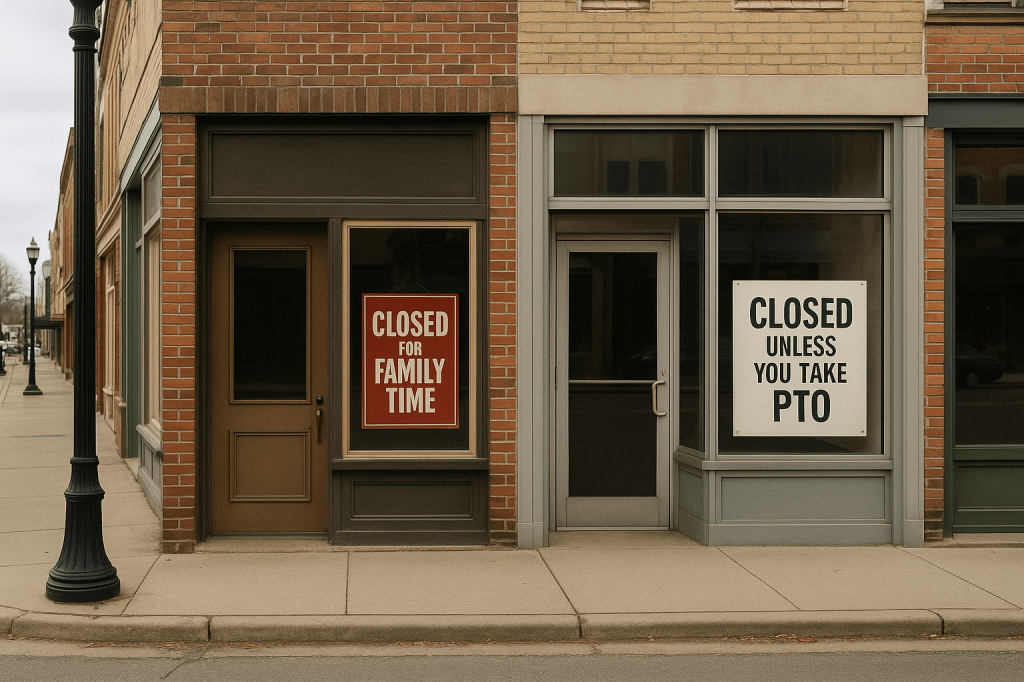

Corporations in the U.S. used to close for multiple days around major holidays because leaders understood or at least accepted that there was social value in allowing workers time for extended connection. Today, many companies force employees to choose between working Wednesday or Friday of Thanksgiving week. Some go further, requiring workers to take PTO to cover days when the company simply prefers not to close. A corporation will not close on the Tuesday before Thanksgiving, even though the value of allowing families an uninterrupted Tuesday-through-Friday stretch is obvious. Instead, the corporate calendar eclipses the communal calendar. Workers do not receive time; they must purchase it back from the company by spending their accrued PTO. What should be a gift of time becomes another transaction.

The same pattern repeats in December. Instead of closing for the week between Christmas and New Year’s, a period that, for generations, represented the one guaranteed moment families could reconnect across states and schedules many companies remain open and again force employees to use PTO if they want to reclaim what was once a near-universal cultural pause. The winter holidays have always been about re-centering the family and revisiting community, but U.S. corporations have built a culture in which reconnection is permissible only if the worker pays for it. Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve often become half-days only in name, with meetings scheduled up until the literal final hours of the year. The commercialization of everything means even time has become a commodity extracted from workers.

This commodification undermines rituals that once anchored communities. Thanksgiving’s meaning has deteriorated because U.S. corporations realized the value of turning the week into a shopping pipeline. Stores began opening earlier and earlier for Black Friday, at one point even opening on Thanksgiving Day itself, pulling millions of workers away from their families and shifting the cultural meaning of the holiday from gratitude to commercial urgency. Though some in-store openings have shifted back toward Friday, the mentality remains: Thanksgiving is now the runway for a sales spectacle. The gravitational pull of Black Friday redefines the whole week.

When a holiday is defined by commerce, its communal value becomes fragile. Families that could have enjoyed Tuesday-through-Friday together now negotiate employer schedules, travel restrictions, and school calendars that increasingly mirror the demands of the market rather than the needs of the community. The commercialization of the holiday season has created a society that knows how to shop together but not how to be together. That shift matters because a community is not sustained by consumption; it is sustained by time.

Time has always been the most essential ingredient of community. But a market-driven society reframes time not as something to invest in people but as something to extract from workers. When time becomes a commodity controlled by corporations, communities lose the ability to structure their own rhythm. Families and neighborhoods cannot coordinate shared rituals when their members’ time is fragmented by different schedules, mandatory workdays, and PTO requirements.

Sundays reveal another layer of this shift. Once the cultural pause of the week, they are now among the most commercially overloaded days in the United States. Football transformed from a pastime into a multi-billion-dollar economic engine that dominates Sundays. The sport is no longer simply a game; it is a national commercial event fueled by advertising, sponsorships, gambling partnerships, data-driven fantasy sports, and a seemingly endless suite of purchasable experiences. The day’s identity shifted from rest to consumption. Even non-fans find themselves orbiting the gravitational pull of the Sunday football economy because it shapes everything: traffic patterns, social gatherings, advertising cycles, and workplace conversations.

Fantasy sports accelerated this shift by financializing fandom. Fans no longer simply cheer for teams; they track player performance as if managing investment portfolios. The language is economic: valuations, projections, buy-low targets, sell-high opportunities. What once required nothing more than showing up and cheering now mirrors the logic of financial markets. Leisure becomes labor, and community becomes competition.

This is the deeper problem: commercialization transforms communal rituals into market events and then convinces people that those market events are the rituals. Communities once relied on shared, non-commercial practices to reinforce identity and belonging. But commercialization dilutes that belonging by replacing shared purpose with shared consumption. A community that once united around a meal now unites around a sales event. A nation that once treated Sunday as a day for collective pause now treats it as a day for collective consumption.

Commercialization does not simply erode existing rituals; it reorganizes values. A society that measures success by economic efficiency will not prioritize communal health. A corporation that sees time as a cost will not voluntarily grant extended holidays. A marketplace that thrives on attention will not tolerate moments of silence. Instead, the market expands into every cultural opening, converting the sacred into the sellable. Tradition becomes branding. Ritual becomes content. Holidays become data points in quarterly reports.

The impact on communities is devastating because community is long-term work. It requires slow, unstructured time. It requires the ability to gather without agenda. It requires rituals that reinforce shared identity rather than shared consumption. When those rituals are continuously squeezed out by commercial demands, communities become thinner, more fragile, and more transactional.

The erosion of extended holiday time is especially damaging for families that live far apart or work demanding schedules. Many households cannot afford to take multiple days of PTO just to recreate the family time corporations once protected by default. The cost of reconnection becomes another barrier to community life. Workers must decide whether to conserve PTO for emergencies or spend it trying to maintain family cohesion. When corporations determine the availability of communal time, families must purchase back their own togetherness.

This problem compounds for low-wage workers, who often lack PTO altogether or work in industries where holiday schedules are inflexible. The people who most need communal time are the least likely to receive it. And when communities lose time, they lose the ability to coordinate culture. Traditions become irregular. Gatherings become sporadic. The predictability that once held communities together dissolves.

Commercialization also changes how people inside communities view one another. When consumption becomes the primary way to participate in culture, individuals begin to see each other not as members of a shared community but as participants in a market. This mindset encourages competition rather than collaboration, individualism rather than collectivism. People learn to evaluate experiences based on personal benefit rather than shared investment. And because commercial experiences are easier to measure you either bought the thing or you didn’t they often overshadow the slower, intangible benefits of community life.

The rise of year-round commercial holidays reveals how deeply this shift has taken root. Major brands now create “shopping seasons” for Valentine’s Day, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, the Fourth of July, Halloween, and even invented micro-holidays like “Friendsgiving” or “Prime Day.” These manufactured events fill every gap on the calendar, ensuring there is always something to consume. The cultural result is a society that never pauses. A community that never pauses cannot reflect, cannot reconnect, and cannot sustain itself. It becomes a collection of individuals moving in the same direction but never meeting in the same place.

The path forward requires redefining what society values. Communities must reclaim time especially the time around major holidays and weekly communal pauses from corporate capture. That means normalizing the idea that Tuesday-through-Friday closures during Thanksgiving week are not indulgent luxuries but necessary investments in social health. It means recognizing that the week between Christmas and New Year’s should be protected for what it historically represented: the one time families could reconnect without the market intruding. It means acknowledging that time is not merely a work resource but a community resource.

Rebuilding community in an era of commercialization requires treating time as sacred. Communities must defend it from monetization, protect it from corporate schedules, and structure their own rituals around it. When people reclaim time, they reclaim each other. When they reclaim each other, they reclaim the possibility of community.

Commercialization wants everything every hour, every holiday, every Sunday, every tradition. Communities cannot survive if they surrender all of it. They can only survive by choosing what will remain unmonetized, unbothered, and unbought. When communities choose to reclaim time, they choose to reclaim themselves.

Five suggestions on how government, new entrepreneurs, and families can recenter:

1. Government Should Legislate Protected Communal Time, Not Just “Holidays”

The U.S. treats holidays as economic opportunities, not civic responsibilities. Government can reverse the trend by formally protecting stretches of time — not single days — around core holidays.

- Make the Tuesday–Friday of Thanksgiving week a state or federally protected family recess period.

- Require companies to close without forcing workers to use PTO for the days before or after a federal holiday.

- Extend similar protected time around Christmas–New Year’s, where many countries already guarantee weeklong holiday pauses.

This isn’t merely cultural; it’s economic. Countries with structured rest periods have higher productivity, lower burnout, stronger communities, and more resilient small-business ecosystems because people actually have time to engage in them.

2. Entrepreneurs Should Build Businesses Designed Around Community Rhythms, Not Quarter-by-Quarter Profit Cycles

New companies — especially those led by first-generation founders, Black founders, or mission-driven founders — can differentiate themselves by rejecting the “always open, always available” business model.

Innovative entrepreneurs can:

- Design businesses that voluntarily close on Sundays and holidays, signaling that community time is part of the brand identity.

- Give employees extended family leave during core cultural seasons, even if competitors do not.

- Build loyalty by centering humanity over profit, a competitive advantage in a burned-out nation.

- Create new economic sectors around rest: wellness retreats, community gathering hubs, shared childcare cooperatives, book lounges, family learning centers.

Companies that protect human time will attract workers, customers, and long-term loyalty far more effectively than companies that burn people out.

3. Families Should Reinstate Non-Commercial Rituals and Treat Them as Sacred

Families have more power than they realize. The market can only colonize a holiday if people participate.

To resist:

- Institute device-free meals, especially on Sundays and during holiday weeks.

- Declare certain traditions non-negotiable and non-commercial, such as potluck dinners, storytelling nights, board game evenings, cooking days, or family walks.

- Celebrate holidays at home instead of at malls, theaters, or commercial venues.

- Mark specific days as “no-buy days” to teach children that value is not tied to consumption.

Families that reclaim ritual reclaim identity — and identity is the strongest defense against commercialization.

4. Communities Should Rebuild Local Institutions That Compete With Commercial Time

When local institutions weaken, corporate culture fills the vacuum. Communities can counter by strengthening their own non-commercial options:

- Community centers that stay open on Sundays for gatherings and learning.

- Neighborhood potlucks, block dinners, or seasonal festivals not sponsored by corporations.

- Skill-sharing circles where neighbors teach each other cooking, budgeting, repairs, gardening, and history.

- Mini-libraries, micro-museums, and small-town storytelling or history nights.

These spaces create a social gravity that pulls people away from fantasy sports, retail calendars, and weekend consumer rituals.

5. National Culture Makers — Writers, Schools, Platforms, HBCUs — Should Reframe Rest as a Citizenship Value

The U.S. treats rest as laziness, even though rest is the foundation of creativity, productivity, and community.

New institutions can step in and shift the narrative:

- Schools can teach the social history of holidays, not just their dates.

- Universities (especially HBCUs) can lead research on rest-economics, community cohesion, and commercial overreach.

- Media outlets and creators can reframe rest as a civic duty, not a weakness.

- Public campaigns can promote “Family Hours,” “Community Time,” or “Disconnect Days.”

When rest becomes culturally honorable, exploitation becomes culturally shameful.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.