“I make no apology for the love of competition.” – John Harbaugh

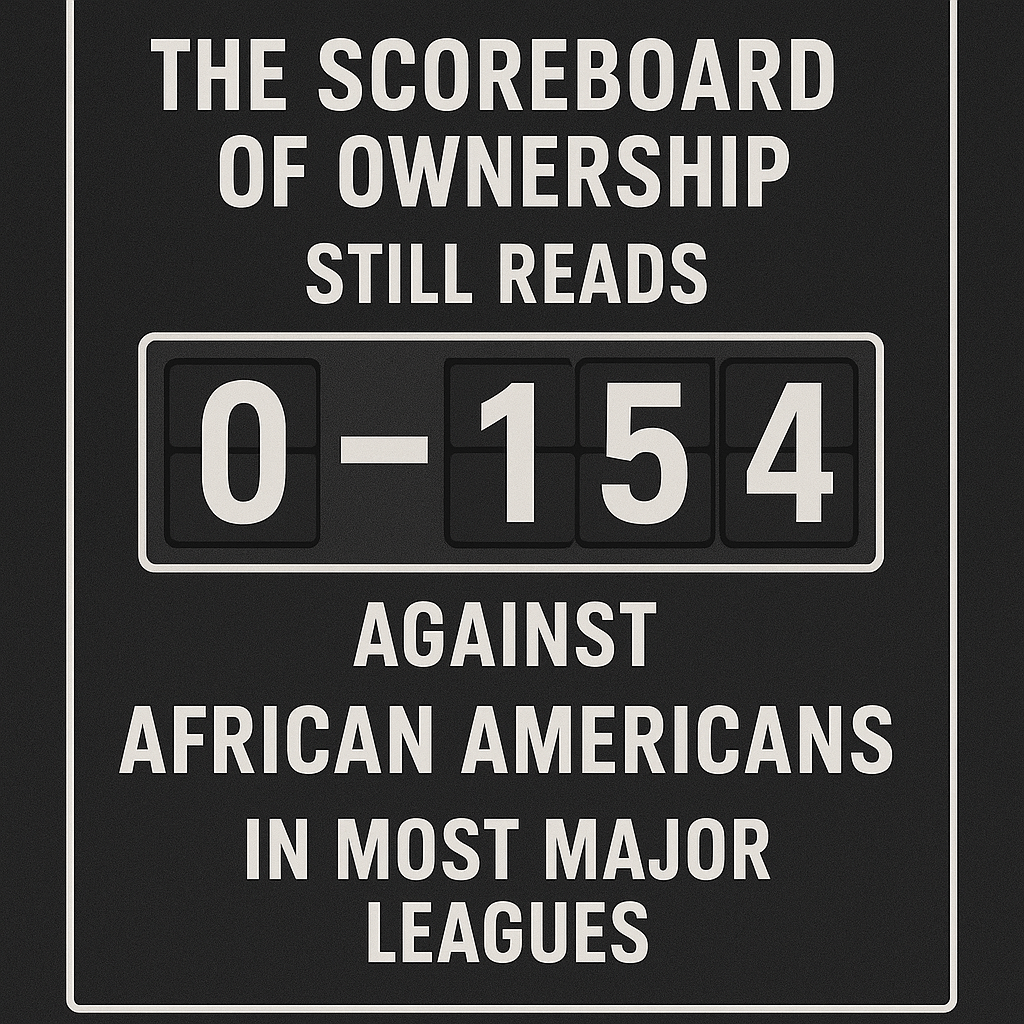

In the world of higher education finance, few numbers turn heads quite like endowment size. It is the ultimate scoreboard for institutional power—a metric that signals not only a university’s wealth but also its capacity to shape research, drive innovation, support students, and influence national policy. In this rarefied air, Howard University has made history, becoming the first Historically Black College or University (HBCU) to surpass the $1 billion endowment mark. According to HBCU Money’s 2024 rankings, Howard’s endowment now stands at $1.03 billion.

Spelman College, long regarded as Howard’s fiercest private competitor, received a record-setting $100 million donation in 2023. Yet even with that windfall, its endowment reached $506.7 million—leaving it more than $500 million behind Howard. Nevertheless, Spelman’s donor base remains one of the strongest in Black higher education, and it may still overtake Howard in the race to $2 billion. But the $1 billion baton has already been passed.

If Howard is chasing Harvard, and Spelman is setting its sights on Yale, then who among public HBCUs dares to chase the Goliath of public university endowments—UTIMCO?

The Silent Behemoth in Texas

UTIMCO—the University of Texas/Texas A&M Investment Management Company—is not just large; it is colossal. As of 2024, UTIMCO manages a staggering $64.3 billion in assets across the University of Texas and Texas A&M university systems. That figure is nearly $15 billion more than Harvard’s own endowment and more than three times the size of the second-largest public university endowment at the University of Michigan.

This financial empire is largely invisible to the public eye. Few outside of elite Texas financial and political circles are even aware of UTIMCO’s existence, let alone its scale. It quietly funds a wide spectrum of research, real estate development, and private equity plays that influence state and national agendas.

If an HBCU—or group of HBCUs—is ever to rival that level of public endowment control, it will not happen by accident. It must be built. And it will most likely be built collectively.

HBCUs and the Endowment Gap

The endowment disparity between HBCUs and Predominantly White Institutions (PWIs) has been well-documented. HBCUs represent around 3% of America’s colleges, yet account for less than 1% of total U.S. endowment wealth. According to a McKinsey report, HBCUs would need $12.5 billion in incremental funding to achieve endowment parity with similarly sized PWIs.

While private HBCUs like Howard and Spelman appear to be making some headway, public HBCUs remain largely behind. Most of them are tethered to state systems that have historically underfunded them and which rarely—if ever—extend the full benefits of their system-wide endowment strategies.

Consider the University of North Carolina System. It includes North Carolina A&T, the largest HBCU by enrollment, and North Carolina Central University. Yet both institutions have endowments under $200 million. Meanwhile, UNC Chapel Hill boasts an endowment exceeding $5.4 billion. Similarly, Florida A&M University has an endowment of less than $200 million, while the University of Florida’s soars above $2 billion.

The Case for a Public HBCU Endowment Challenger

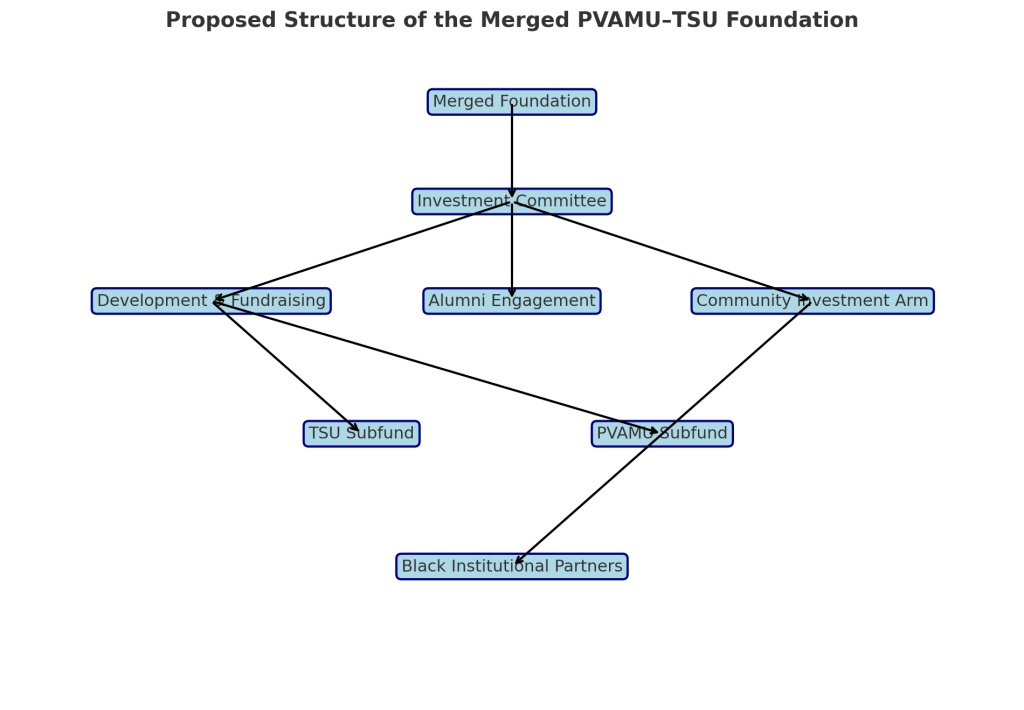

In identifying a public HBCU capable of mounting a challenge to UTIMCO’s financial supremacy, the most promising strategy does not lie in the strength of one institution—but in the collective power of several. States that are home to multiple public HBCUs present the most viable path to establishing a unified, independently managed investment entity that can leverage scale, pooled capital, and institutional collaboration.

Virginia, Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Mississippi all house two or more public HBCUs, each with proud legacies and strategic regional influence. A coordinated financial framework across these schools could form the foundation of a “Black UTIMCO”—a professionally managed, state-based consortium endowment capable of rivaling small PWI systems in both return and influence.

The most likely candidates must share a few key characteristics:

- State-Level Endowment Consortium Model – States with two or more public HBCUs, such as Virginia (Virginia State, Norfolk State), Georgia (Albany State, Fort Valley State, Savannah State), or Alabama (Alabama A&M, Alabama State), are uniquely positioned to pioneer a collective endowment strategy. Rather than relying on marginal support from broader university systems, these HBCUs could form a joint investment vehicle modeled on UTIMCO—pooling their endowments under a professionally managed, independent investment company. Such a fund would enable economies of scale, competitive asset management, and unified long-term planning, boosting their ability to generate investment alpha and philanthropic leverage.

- Flagship Status Among HBCUs – Institutions with strong alumni networks, national reputations, and federal research capabilities are better positioned to attract major philanthropy.

- Strategic Location – HBCUs located in fast-growing economic zones can leverage regional corporate ties for private partnerships.

However, creating such a financial architecture is not purely a technical endeavor. It is inherently political—and often fraught with social resistance.

The Political Geography of Resistance

Many of the states that host multiple public HBCUs are governed by conservative legislatures and state boards of regents that have long resisted equitable funding for Black institutions. Despite proclamations about diversity, equity, and inclusion, these power structures often withhold support from Black-led entities that could challenge traditional hierarchies.

- Alabama, with Alabama State and Alabama A&M, underfunded its HBCUs by over $527 million between 1987 and 2020, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

- Georgia’s consolidation of HBCUs like Albany State into broader system structures has often diluted their financial and governance autonomy.

- Mississippi has repeatedly neglected basic infrastructure and funding needs at its three public HBCUs—Jackson State, Alcorn State, and Mississippi Valley State—despite allocating surpluses elsewhere. It is also no secret that Mississippi has purposely constructed a singular board of trustees for all of its public higher education institutions across the state with Ole Miss and Mississippi State unabashedly dominating the board.

Even in Virginia, perceived as more moderate, a move by Virginia State University and Norfolk State to pool their endowments might be seen as too bold a play in a state that still subtly resists Black institutional consolidation.

Social Impediments and Institutional Fragmentation

Beyond politics, there are intra-HBCU dynamics that complicate collaboration. These institutions have historically been forced to compete for scraps, which can breed a zero-sum mentality. Trustees, alumni, and administrations often prefer complete local control over modest assets rather than shared governance over substantial ones.

Convincing institutions to pool their endowments requires cultural alignment and a long-term vision of shared prosperity. Donors, too, may resist giving to multi-institutional funds, preferring the emotional appeal of a singular alma mater.

Nonetheless, this mindset must change. The math is clear: five public HBCUs each contributing $100 million can produce a $500 million investment base. That scale opens doors to private equity, hedge funds, and other vehicles that outperform the conservative allocations typically used by smaller institutional portfolios.

Institutions Poised for Leadership

- North Carolina A&T State University, with an endowment of $201.9 million, remains the largest public HBCU endowment. With deep ties to tech and defense industries, it has both alumni momentum and industry leverage.

- Florida A&M University, despite setbacks surrounding its pledged $237 million donation, has an official endowment of $124.1 million and stands to benefit immensely from partnership with institutions like Bethune-Cookman or Edward Waters.

- Virginia State University and Norfolk State University, with $96.5 million and $88.2 million respectively, could combine to form the financial cornerstone of a Virginia HBCU Investment Company—managing nearly $185 million in assets at inception.

The Need for a “Black UTIMCO”

Rather than wait for state systems to share the wealth equitably, some in the HBCU policy space are advocating for the creation of a consortium endowment fund — a kind of “Black UTIMCO.” This collective endowment manager would pool assets from willing HBCUs, allowing them to negotiate better investment terms, lower fees, and generate alpha through scale.

Such an initiative would require governance innovation, donor transparency, and trust between institutions that are often underfunded and overburdened. But it may be the only viable path forward for public HBCUs to compete against mega-managers like UTIMCO, MITIMCo, or the Yale Investments Office.

A $5 billion consortium fund, even divided across 25 HBCUs, would be transformational. It could fund scholarships, capital improvements, faculty chairs, and technology upgrades, while giving HBCUs the financial leverage to attract major federal research grants.

A New Competitive Mindset

In American higher education, the metaphorical arms race is very real. Endowments are the stockpiles. Harvard and Yale are the gold standard in the private arena. UTIMCO is the titan in the public sector. And HBCUs, despite their contributions to Black excellence, continue to be locked out of the upper tier.

John Harbaugh’s quote about competition resonates because it points to a deeper truth: love of competition does not require parity at the outset, only the will to chase. Howard is in the final lap toward $1 billion, setting a new bar for Black institutional capital. Spelman may outdistance them on the next lap to $2 billion. But in the public sphere, the silence is deafening.

Where is the public HBCU that dares to dream of beating Michigan, surpassing UNC, or even challenging UTIMCO?

The Race Begins with Vision

Howard is chasing Harvard. Spelman is perhaps chasing Yale.

But no single public HBCU can chase UTIMCO. The scale is too vast, the machinery too entrenched, and the rules too uneven.

What public HBCUs can do, however, is combine. They can look across their borders, past their rivals, and toward a shared future. They can imagine a world where collective African American endowment power reshapes not just education, but the broader economy and policy landscape.

It is not a failure of ambition that no public HBCU has reached $1 billion. It is a failure of coordination and imagination.

The first African American UTIMCO will not be built by a single school. It will be built by a desire for compeition. A desire to win.