“A gift can open a door, but only ownership lets you walk through it on your own terms.”

When Prairie View A&M University announced that it had received a historic $63 million unrestricted gift from philanthropist MacKenzie Scott, headlines celebrated the moment as a watershed for the institution, the Texas A&M University System, and the broader HBCU sector. It was framed as both a moral recognition of PVAMU’s legacy and a financial turning point that would catalyze new academic, cultural, and research frontiers.

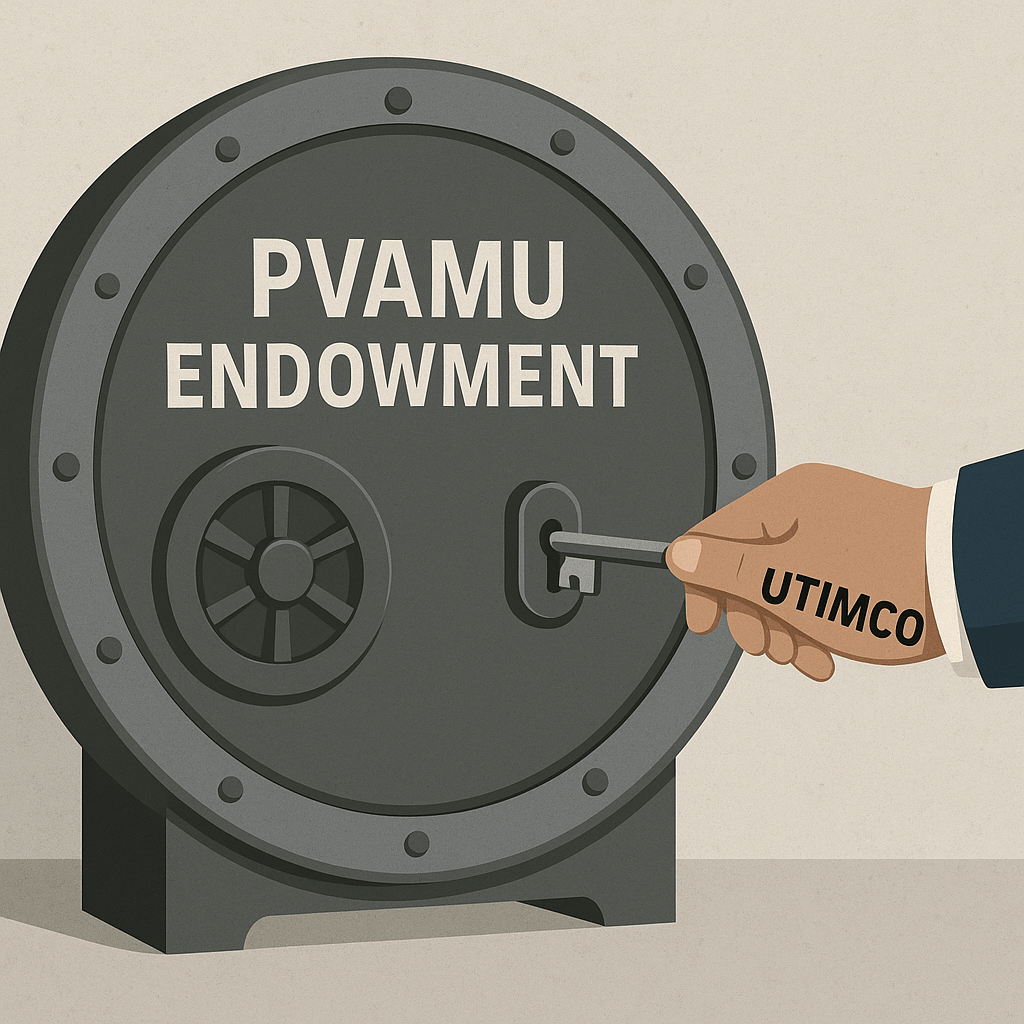

And yet, behind the applause and the very real gratitude there remains a more sobering, structural reality: Prairie View does not actually control its capital. The university’s endowment, like that of all Texas A&M System schools, is controlled and managed by UTIMCO, the University of Texas/Texas A&M Investment Management Company. UTIMCO is one of the largest public endowment management entities in the United States, overseeing well over $70 billion in assets. It is powerful, sophisticated, and critically not directly accountable to Prairie View’s leadership or the African American community whose future PVAMU represents.

This is the overlooked truth in the philanthropic triumph narrative: historic gifts do not necessarily translate into historic power. And power, not simply capital, is the currency African American institutions have always lacked most in the American economic order. Prairie View A&M University’s situation is a case study in the difference.

This article explores:

- Why Prairie View’s record-setting gift still leaves it structurally dependent

- How UTIMCO’s control restricts the institution’s long-term sovereignty

- What this tells us about HBCU philanthropy and institutional design

- Why African American institutional power requires ownership, not just funding

- What steps Prairie View, other public HBCUs, and African American philanthropists can take to change the paradigm

This is not about questioning the value or impact of MacKenzie Scott’s generosity. It is about ensuring that gifts to African American institutions actually translate into durable, compounding power not momentary uplift that still sits under someone else’s governance.

The Gift Was Unprecedented—But the Structure Wasn’t

MacKenzie Scott’s philanthropic investments in Prairie View were transformational by any measure. Unrestricted capital is rare. Unrestricted capital at that scale is almost unheard of for HBCUs. Prairie View announced bold plans: initiatives in student success, research expansion, recruitment of top scholars, and community-facing programs that would have immediate impact.

However, beneath these aspirational goals lies a structural constraint. As a member of the Texas A&M University System, Prairie View’s endowment assets are not independently managed. Instead, they are placed under UTIMCO stewardship.

This means:

- Prairie View cannot choose its own investment strategy

- Prairie View cannot decide its own risk profile

- Prairie View cannot determine long-term reinvestment philosophies

- Prairie View cannot directly leverage its endowment as collateral or strategic capital

- Prairie View has limited input into how its own financial future is shaped

Prairie View is wealthy in name, but not in governance. This is the difference between having money and having power.

Why UTIMCO Control Matters

UTIMCO is a financial powerhouse. It runs an endowment strategy modeled on the “Yale model” of diversified, high-yield, alternative-asset heavy investing. Its size gives it access to premier private equity, hedge funds, venture capital, and global asset vehicles that smaller endowments could never reach. But Prairie View is not UTIMCO’s strategic priority. And Prairie View does not have representation proportionate to its needs, mission, or history on the governance side of the investment enterprise.

The problems with this arrangement are structural, not personal:

1. Prairie View’s capital becomes part of a system that does not share its cultural mission.

UTIMCO’s fiduciary responsibility is to the entire system—primarily UT Austin and Texas A&M University, the two flagship institutions with the largest political influence and endowment weight.

2. Prairie View does not benefit proportionately from its own growth.

When UTIMCO’s investments outperform, the rising tide lifts the entire system but Prairie View’s small allocation does not allow it to meaningfully influence direction or capture outsized opportunity.

3. Prairie View is locked out of using its endowment to build independent institutional leverage.

For example:

- Launching Prairie View–controlled venture funds

- Building independent real-estate portfolios

- Creating sovereign partnerships with African universities

- Developing major research parks or revenue-producing assets

- Issuing bonds based on endowment performance

- Using the endowment to create a Prairie View Development Corporation

- Deposit into African American Owned Banks

These are the exact strategies that allow elite institutions to become global players. Without endowment control, Prairie View cannot follow the same playbook.

4. African American institutional power remains externally governed.

Even when philanthropy flows to us, governance does not.

This is the core dilemma.

The Limits of Public-Sector HBCU Philanthropy

Public HBCUs occupy an uncomfortable position in American philanthropy. They exist inside systems created by and for institutions that do not share their origin story, demographic composition, or cultural mission. As a result, public HBCUs rarely benefit from the full compounding power that large donations should create. A $63 million donation to a private HBCU with full endowment control is a generational shift. A $63 million donation to a public HBCU inside a state-controlled investment empire is uplift but not sovereignty. The structure, not the gift itself, limits the long-term multiplier effect.

The True Power of an Endowment Is Governance, Not Size

The most elite universities such as Harvard, Yale, Stanford understand that the endowment is not merely a pot of money. It is the engine of independence, the foundation of strategic risk-taking, and the vault that allows them to pursue multi-century planning horizons. Prairie View’s endowment, while larger than before, becomes one more line item inside a massive investment entity whose priorities were never designed around the empowerment of African American institutions.

This raises fundamental questions:

- If Prairie View doubled or tripled its endowment, would it gain any more control?

- If Prairie View received a $500 million gift tomorrow, would it govern that capital?

- What does “wealth” mean if the institution cannot direct it?

These questions get at the heart of African American philanthropic strategy:

Power is not the receipt of capital it is the control of capital.

Why This Matters for African American Philanthropy

The African American community is entering a new era of giving. Donors both internal and external to the community are showing increased willingness to fund African American institutions, particularly HBCUs. But if those donations sit inside structures that we do not control, then the long-term compounding advantage is lost. Philanthropy that uplifts without empowering is charity. Philanthropy that transfers capital and governance is institution-building. Prairie View deserves the latter. All HBCUs deserve the latter. African America deserves the latter.

What Would It Look Like for Prairie View to Have Full Capital Control?

If Prairie View controlled its own endowment strategy, several catalytic changes could occur:

1. PVAMU could launch its own independent investment office.

This would allow:

- Hiring Black fund managers

- Building partnerships with African investment firms

- Investing directly in Prairie View–based startups

- Growing an internal investment culture among alumni and students

2. PVAMU could build a multibillion-dollar research and development ecosystem.

The endowment could seed:

- A Prairie View Innovation Corridor

- A Black-owned semiconductor research consortium

- Autonomous vehicle labs

- Agricultural technology incubators

- An African Diaspora science and engineering exchange

- A rural Texas innovation hub exporting expertise globally

3. PVAMU could pursue independent financial engineering strategies.

Including:

- Issuing bonds based on endowment earnings

- Creating a real estate trust

- Launching a PVAMU-controlled venture fund

- Building a revenue-producing hospital network

- Constructing Prairie View–owned student housing developments

4. PVAMU could fundamentally reshape African American institutional futures.

With full investment autonomy, Prairie View could become:

- A national model for Black endowment governance

- A financial anchor for African American rural communities

- A bridge between Texas and the global African Diaspora

- A site of intergenerational wealth-creation for African American students

- An institution that attracts not only students but developers, scientists, and investors

This is the scale of possibility currently constrained by UTIMCO governance.

What Needs to Change—A Philanthropic and Policy Framework

To transition from uplift to sovereignty, African American leaders, donors, and policymakers must pursue concrete reforms:

1. Public HBCUs must secure special provisions for independent endowment management.

This could include:

- Carve-outs from state systems

- Special legislative exemptions

- Hybrid governance models where system oversight continues but investment control shifts with the ultimate goal of full sovereignty

2. Large donors should explicitly require endowment autonomy as part of major gifts.

Imagine if MacKenzie Scott had stipulated:

“This gift must be placed in a separately managed fund controlled solely by Prairie View A&M University and its own designated board of trustees.”

That single sentence would have changed the institution’s next 100 years.

3. Prairie View alumni must build parallel philanthropic capital pools.

This includes:

- Alumni-controlled investment funds

- Prairie View-specific donor-advised funds

- Community investment vehicles

- A Prairie View Cooperative Endowment Fund

These independent vehicles can partner with but not be controlled by state systems.

4. National African American institutions must lobby for HBCU endowment independence.

A single policy shift could alter the landscape for every public HBCU:

Public HBCUs must have governance authority over capital donated specifically to them.

A Moment of Truth for HBCU Philanthropy

Prairie View’s historic gift was a moment of celebration—but also a moment of clarity. If African American institutions cannot control the endowments gifted to them, then the path to sovereignty remains blocked.

The philanthropic sector must confront this truth:

We cannot build African American power without African American control of African American capital.

Prairie View A&M University has always carried a dual identity, an HBCU of national importance inside a system not built for it. The generosity of donors like MacKenzie Scott can change the scale of Prairie View’s work, but only structural reform can change the nature of Prairie View’s power. The next era of HBCU philanthropy cannot simply be about larger gifts. It must be about gifts that come with governance, strategy, and autonomy.

Because endowments don’t build institutions.

Endowment sovereignty does.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.