Philanthropy is not about the money. It’s about using whatever resources you have at your fingertips and applying them to improving the world. — Melinda Gates

The conversation about African American philanthropy often focuses on external barriers: systemic racism, wealth gaps, and institutional discrimination. While these factors are undeniably significant, there exists an equally important yet frequently overlooked challenge—the internal dynamics within the African American community that impede the development of sustainable philanthropic infrastructure. Understanding these challenges requires an honest examination of seven distinct groups whose attitudes and behaviors collectively create obstacles to building the financial institutions necessary for long-term community empowerment.

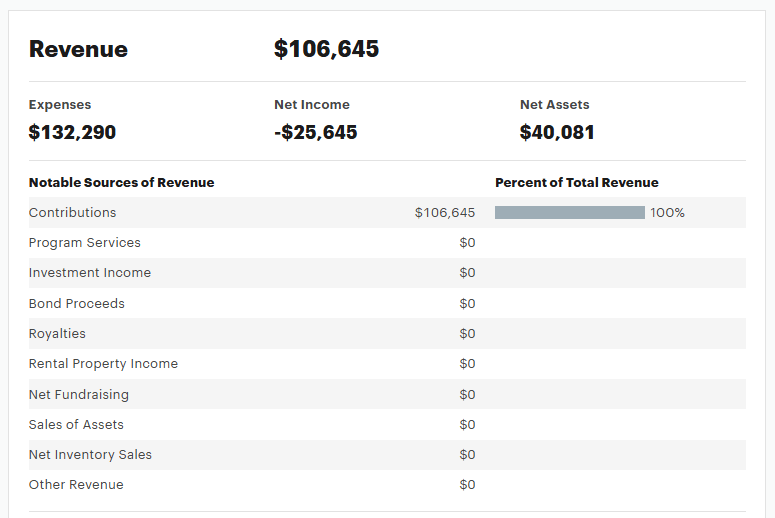

Before exploring these seven groups, it’s essential to understand what’s at stake. African American philanthropic institutions from educational endowments to community foundations, from cultural preservation organizations to economic development funds face a perpetual funding crisis. While individual acts of giving within the Black community are robust, the institutional infrastructure that could amplify, sustain, and strategically deploy these resources remains underdeveloped compared to other communities. This infrastructure gap isn’t merely about money; it’s about the systems, organizations, and endowments that create generational impact and community resilience.

Group One: The Self-Rejecting

Perhaps the most painful barrier comes from African Americans who harbor deep-seated negativity toward anything associated with Blackness. This group actively opposes, undermines, or refuses to support Black institutions not from ignorance or indifference, but from internalized anti-Blackness. They may have achieved individual success by distancing themselves from Black community spaces, or they may carry unexamined prejudices absorbed from the broader society.

These individuals often channel their resources toward non-African American institutions while viewing Black-focused organizations with suspicion or contempt. Their influence extends beyond their personal giving decisions; they frequently occupy positions of influence where they can discourage others from supporting Black institutional development. This group represents a fundamental breach in community solidarity that no amount of external fundraising can overcome.

Group Two: The Uncommitted

The second group doesn’t harbor hatred toward Black people or institutions, but they fundamentally don’t understand why Black-specific institutions matter. These are often well-meaning individuals who subscribe to a colorblind ideology, believing that supporting non-African American institutions adequately serves everyone, including African Americans. They ask, “Why do we need a Black college fund when there are already scholarship programs?” or “Why create a Black community foundation when established foundations exist?”

This group fails to recognize that non-African American institutions have historically underserved Black communities and that Black-led institutions bring cultural competency, trust, and targeted impact that general-purpose organizations cannot replicate. Critically, they fail to see that what appears “mainstream” or “universal” is often simply another community’s institution presented as neutral. The Evers Institute is clearly perceived as an African American organization, but the Ford Foundation is rarely identified as a European American institution yet both serve their founding communities’ interests and perspectives first. Harvard is seen as an elite university, not as a European American institution, while Howard is marked as a historically Black university. This perceptual gap prevents many African Americans from recognizing that other communities have always built and maintained their own institutional infrastructure, and that supporting Black institutions isn’t separatist it’s simply doing what every thriving community does. Their indifference rooted not in malice but in a failure to understand structural inequality means they direct their philanthropic dollars elsewhere, often to institutions that may never prioritize Black community needs.

Group Three: The Institutionally Unaware

The third group operates in a state of institutional blindness. They don’t actively oppose Black institutions, nor do they question their value—they simply don’t think about institutional development at all. These individuals may support individual causes or give to immediate needs, but they lack awareness of the institutional infrastructure that could sustainably address community challenges.

This group doesn’t realize that African American communities lack equivalents to the well-endowed foundations, think tanks, policy institutes, and cultural institutions that other communities have built over generations. They don’t consider that creating such institutions is even possible or necessary. Their philanthropy, when it exists, tends toward reactive giving—responding to crises rather than investing in the systems that could prevent them. This lack of institutional consciousness represents a failure of vision that keeps the community dependent on external resources and goodwill.

Group Four: The Delegators

The fourth group recognizes the need for African American institutions but believes funding them is someone else’s responsibility. They might think wealthy Black celebrities should handle it, or that government programs should fill the gap, or that white philanthropists should fund Black institutions out of historical obligation. Some in this group pursue alternative approaches to sustainability that avoid the hard work of building financial infrastructure—seeking grants, pursuing partnerships, or relying on in-kind contributions instead of creating independent funding streams.

While these alternative approaches have their place, this group’s fundamental error is abdicating personal responsibility for institutional sustainability. They want the benefits of strong Black institutions without contributing to their financial foundation. This mindset creates institutions that remain perpetually under-resourced and dependent, unable to plan long-term or weather financial storms because their funding base is unreliable and externalized.

Group Five: The Financially Unable

The fifth and largest group encompasses everyone who genuinely cannot afford to support African American institutions financially. The racial wealth gap is real and devastating: the median white family has nearly eight times the wealth of the median Black family. Many African Americans are still recovering from predatory lending, employment discrimination, and the compounding effects of historical wealth extraction. They live paycheck to paycheck, carry substantial debt, and lack disposable income for philanthropic giving.

This group’s inability to give is not a character flaw but a structural reality created by centuries of economic oppression. However, their numerical size means that African American philanthropic infrastructure cannot rely primarily on small donors in the way that some other causes have successfully done. Building sustainable institutions requires cultivating major donors and creating wealth-building strategies within the community that generate philanthropic capacity over time. The challenge lies in building institutional infrastructure while acknowledging that most potential supporters are themselves struggling financially.

Group Six: The Promisers

The sixth group may be the most frustrating for those trying to build sustainable institutions. These are the individuals who express enthusiastic support, make commitments, and promise resources—but then fail to follow through. They attend planning meetings, serve on boards, pledge donations, and create expectations, only to disappear when it’s time to deliver.

Sometimes this happens due to changing circumstances, but often it reflects a lack of serious commitment from the outset. These individuals enjoy the social capital and recognition that comes from appearing philanthropic without making the actual sacrifice of resources. Their broken promises create budgeting nightmares for institutions, forcing organizations to scale back programs, delay initiatives, or scramble for alternative funding. Perhaps worse, they create cynicism and distrust that makes it harder to cultivate genuine supporters in the future.

Group Seven: The Grassroots Purists

The seventh group believes that everything can and should be accomplished through grassroots organizing, volunteer labor, and community sweat equity. They view institutional infrastructure and professional philanthropy with suspicion, seeing it as elitist or as selling out authentic community organizing. While grassroots efforts are vital and have accomplished tremendous things, this group fails to recognize that grassroots approaches alone cannot create the sustained, large-scale infrastructure necessary for generational change.

Building endowments, creating professional organizations, developing real estate holdings, establishing grantmaking foundations—these require capital, expertise, and institutional structures that cannot be crowdsourced or volunteer-run indefinitely. The grassroots purist approach, while rooted in legitimate democratic values and community empowerment principles, inadvertently keeps African American institutions small, informal, and vulnerable. It privileges authenticity over sustainability and fails to recognize that other communities have achieved their institutional strength precisely by moving beyond purely grassroots models.

The work ahead is challenging, but understanding these seven groups provides a clearer map of the terrain. With that map, those committed to building sustainable African American philanthropic infrastructure can navigate more strategically, building institutions designed to overcome these very human barriers to collective progress.

Recognizing these seven groups is not about assigning blame but about developing strategies that account for these realities. Building sustainable African American philanthropic infrastructure requires addressing each barrier specifically. It means creating cultural interventions that combat internalized anti-Blackness, educational campaigns that explain why Black institutions matter, and consciousness-raising about institutional development. It requires cultivating a culture of personal responsibility for community institutions while simultaneously addressing the structural factors that limit Black wealth.

Most importantly, it means building with the understanding that these barriers exist—creating institutions that can survive and thrive even when significant portions of the potential support base are unavailable, uncommitted, or actively opposed. This isn’t pessimism; it’s realism. And from that realism comes the possibility of building philanthropic infrastructure that can genuinely sustain African American community advancement for generations to come. The path forward demands both clear-eyed acknowledgment of these internal challenges and unwavering commitment to building despite them, creating a foundation strong enough to support not just this generation but those yet to come.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ClaudeAI.