“Pragmatism is good prevention for problems.” – Amit Kalantri

The unspeakable may be the fiscally responsible

It seems almost unthinkable. An HBCU football game without BOTH bands at halftime. It has happened before, though only in exceptional cases: an emergency back home, a suspended band, or budgetary chaos. But to purposely and preemptively not take one’s band on the road? In HBCU culture, it feels akin to breaking the thirteenth commandment—Thou Shall Not Not Make ‘Em Dance—or committing some kind of cultural apostasy. Yet, for all its sacredness, perhaps it is time to break the spell.

At the core of this radical idea lies a rather mundane but pressing question: money. Football remains a major cost centre for most HBCUs. Marching bands, while sources of school pride and cultural magnetism, are not cheap to move. Between buses, meals, lodging, uniforms, and instrument logistics, taking a full band of 150+ members on the road can easily cost upwards of $50,000 per trip—especially if the destination is cross-country or involves air travel. Multiply that over several away games and a program could be looking at a mid-six-figure expenditure for the season. For many financially struggling HBCUs, this is no longer tenable.

The Holy Trifecta: Football, Bands, and Black Culture

At HBCUs, the band is often a co-headliner alongside the football team. In fact, at many institutions, the halftime show garners more social media views than the football game itself. The human formations, the drumline cadences, the high-stepping majorettes—it is part performance art, part cultural ritual. This makes the suggestion to leave bands behind feel almost blasphemous. It would strip the game of a vital sensory component, some argue, and deflate the inter-institutional competition that thrives on the duality of football and music.

Yet, it is precisely because of the power and prestige of the band that its role should be more strategically deployed. Bands are brand equity, not just background music. And that equity can be preserved—even enhanced—by rationing its presence and reallocating its costs.

Opportunity Cost and the Marching Million

Take the example of a mid-tier HBCU football program with four away games and a 160-member band. Transporting that band to all four games (via coach buses and lodging in modest hotels) might cost around $45,000 per game, or $180,000 total. Now imagine what else $180,000 could fund:

- A student internship fund supporting 60 summer internships with $3,000 stipends;

- A marketing campaign aimed at boosting out-of-state recruitment;

- Repairs to the music department’s aging instruments and facilities;

- A reserve fund for the band itself, to increase scholarships or buy newer uniforms.

The fact that this trade-off rarely enters the conversation reflects how entrenched the band has become as a required amenity for HBCU athletics. But institutions facing increasing competition for enrollment, state budget cuts, and inflationary pressure must start examining what truly maximizes impact—and what has become tradition for tradition’s sake.

Enter the Bandlight Policy

A “Bandlight” policy—where the band does not travel to away games unless deemed a high-profile or high-impact matchup (such as classics or homecoming of an opposing school)—could preserve institutional pride while enabling budget reprioritization. To soften the cultural blow, this policy could be paired with livestreamed pregame performances from home, aired during halftime of away games, or partnerships with local high schools or community colleges to fill the halftime slot. In effect, HBCUs would still “show up” culturally—just not logistically.

Moreover, rival institutions could enter into alternating-year agreements where only one band travels per year to the same matchup, thereby cutting costs in half while preserving some tradition. Or the entire conference could collectively implement policies to standardize expectations.

Revenue Substitutes: Making Absence Profitable

There is also the question of replacement: if the band is not traveling, what can be put in its place—socially and economically?

- High School Recruitment Fairs: Away games, especially those in recruiting hotbeds like Atlanta, Dallas, or Memphis, could feature pre-game recruitment fairs or pop-up university expos that target prospective students. Hosted in the parking lots or auxiliary spaces near stadiums, these expos would draw interest beyond the usual alumni tailgating crowds and create a broader community impact.

- Alumni Investment Summits: Rather than just tailgates and chants, HBCUs could host micro-investment forums or alumni networking mixers tied to away games. These could feature information on planned giving, institutional capital needs, and legacy endowments. Such events reinforce the university’s brand as an enduring institution—not just a weekend pastime.

- Cultural Diplomacy Exchange: At many PWIs (Predominantly White Institutions), the visiting HBCU band often provides the primary Black cultural presence on campus. By not sending the band, HBCUs could instead host curated cultural experiences: pop-up film screenings of Black directors, panel discussions on African American history, or mini art exhibitions. These events would still showcase the university’s heritage—just in a different form.

- Digital Monetization: Finally, there is room for digital alternatives. Bands could record exclusive halftime content back on campus for broadcast during away game livestreams. With the right sponsorship and media packaging, this could even generate revenue—especially if made accessible to the broader HBCU diaspora via streaming platforms or partnerships with outlets like HBCU Go or KweliTV.

Making Room for Exceptions: The Classics, Championships, and Cultural Diplomacy

No policy should be absolute, and the “Bandlight” approach must leave room for strategic exceptions. Certain games carry weight not just in terms of school pride, but institutional visibility, alumni engagement, and revenue generation. These events—such as the Bayou Classic, Magic City Classic, Florida Classic, or Celebration Bowl—should remain exempt from the policy due to their national reach and cultural cachet.

In these cases, the financial and branding benefits of both bands being present far outweigh the costs. These events are often broadcast on national television, command six- or seven-figure sponsorships, and serve as major alumni gathering points. Not showing up in full force—band and all—would send the wrong message about the value of HBCU pageantry.

Similarly, championship games or playoffs should remain occasions where bands accompany the team, reinforcing institutional pride at the highest level of competition.

Lastly, special exceptions could be granted for “Cultural Diplomacy Games,” where HBCUs play PWIs in regions with limited exposure to African American cultural institutions. These matchups offer an opportunity to expand HBCU brand identity and cultural influence—missions that justify a larger financial investment.

By clearly defining such exceptions, institutions can retain flexibility without undermining the integrity of a more fiscally responsible standard for regular-season games.

From Brass to Bank: Strengthening Endowments Through Smart Savings

Perhaps the most compelling reason to consider limiting band travel is the long-term impact it could have on strengthening HBCU endowments—a chronic weakness in the financial armor of most historically Black colleges and universities. Endowments are not merely rainy-day funds; they are the bedrock of institutional independence, providing reliable income streams for scholarships, faculty retention, infrastructure improvements, and strategic initiatives. Yet, the vast majority of HBCUs remain dangerously undercapitalized.

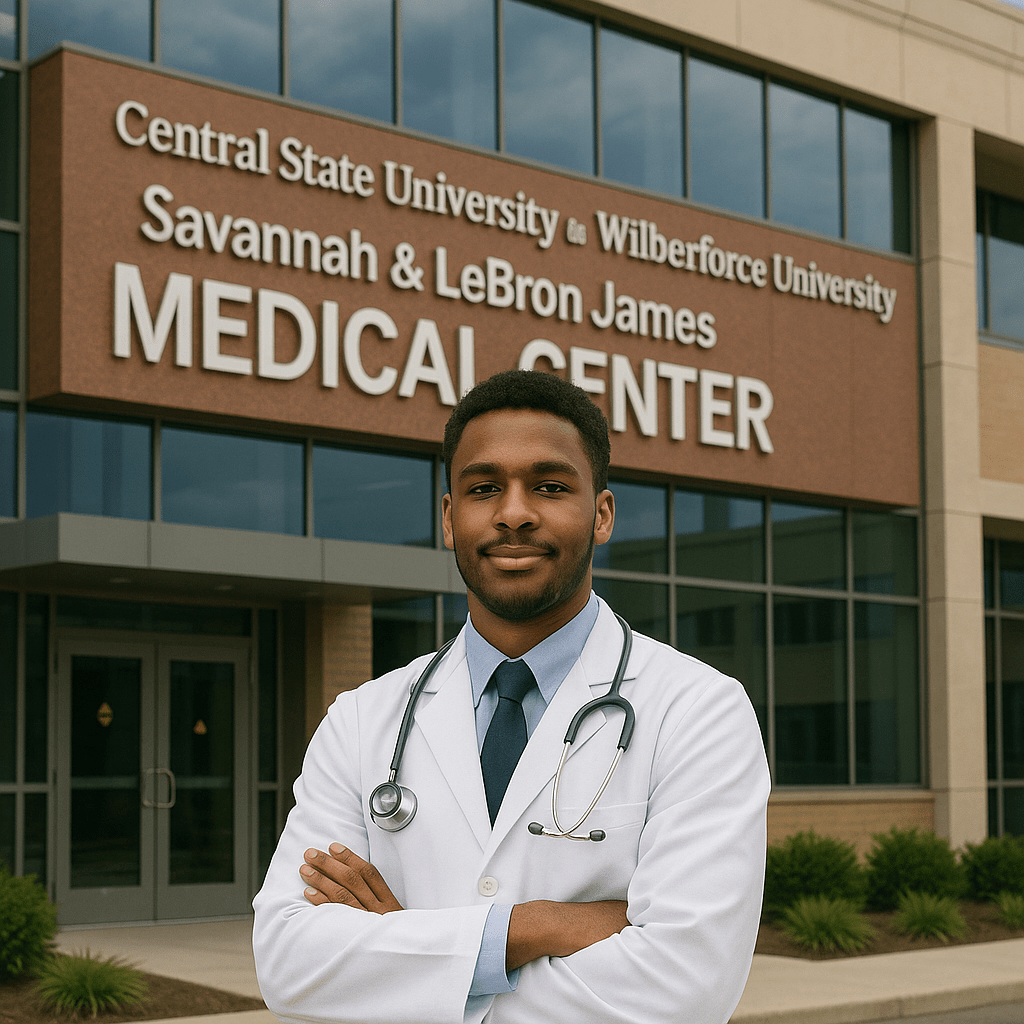

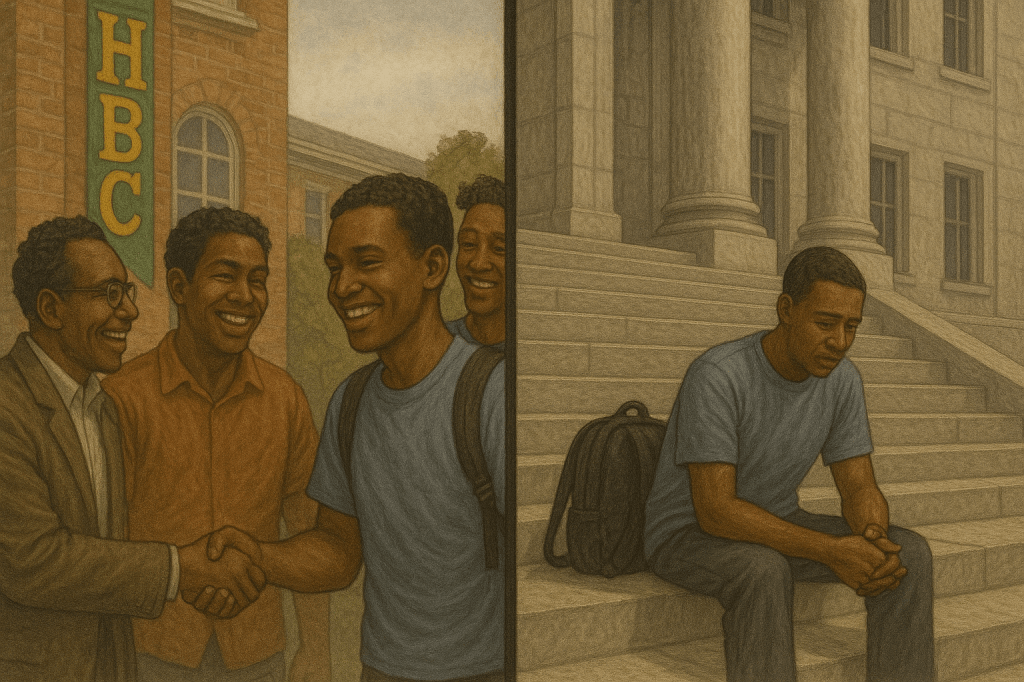

As of 2024, only one HBCU—Howard University—has an endowment exceeding $1 billion. By comparison, over 50 predominantly white institutions boast endowments larger than $1 billion, and the average Ivy League endowment surpasses $10 billion. The gap in financial flexibility means that most HBCUs remain reliant on tuition, federal grants, and unpredictable philanthropic cycles. Closing this endowment divide must be a generational project—and rethinking every cost center, including football and band logistics, is a prudent step.

Let us revisit the travel cost scenario: an HBCU saves $180,000 annually by not sending its marching band to four away games. If that amount were instead directed into an endowment or investment fund yielding a 10% annual return, compounded over 30 years, the return on the first year’s investment alone would grow to approximately $3.1 million. But in practice, this contribution would not be a one-time deposit—it would be made every year for 30 years.

Each $180,000 annual deposit would compound over a different span of time—from 30 years down to 1 year for the final contribution. When we sum the compounded growth of all 30 annual contributions, the total value by year 30 is not merely $3.1 million, but a remarkable $32.6 million.

This is the true power of consistent, disciplined investing. What might seem like a relatively small annual sacrifice—foregoing band travel to four away games—can, when reinvested wisely, build a financial pillar for an HBCU that could support hundreds of scholarships, faculty lines, or capital improvements. Across multiple institutions, such strategy would not just close the endowment gap—it could transform it into a long-term competitive advantage. Using the future value formula:

FV = P × [(1 + r)^t – 1] / r

FV = $180,000 × [(1.10)^30 – 1] / 0.10

FV ≈ $3.1 million

Now imagine 40 HBCUs adopting this policy. If each institution redirected $180,000 annually into an endowment with a 10% annual return, the combined value of those contributions over 30 years would grow to an extraordinary $1.3 billion.

This isn’t speculative—it is mathematical certainty backed by compounding returns. What begins as a quiet cost-saving measure becomes a billion-dollar transformation of Black institutional capital. It is the kind of long-term vision HBCUs need to build financial independence and power. Leaving the bands at home, selectively and strategically, could finance a future where they never again play second fiddle to structural underfunding.

Such funds could be reserved for band scholarships, new instruments, music department endowments, or general institutional advancement. Equally important, this shift demonstrates fiscal maturity to large philanthropic donors who seek assurance of sustainability and capital stewardship. In this light, the silence of a band on one Saturday becomes a long crescendo toward institutional resilience.

Band Camp Economics and Reallocation Potential

Consider also the economic pressures on the bands themselves. Marching bands at HBCUs are often underfunded even as they serve as ambassadors and talent pipelines. Travel budgets could be redirected internally:

- Higher stipends for band scholarships, which could attract more top talent;

- Expanded outreach to middle and high school band programs to sustain the pipeline;

- Better faculty-to-student ratios for music education;

- New instrument purchases, particularly for percussion and brass sections, which endure high wear and tear.

An internal reallocation of $150,000–$250,000 annually per school could mean the difference between merely surviving and thriving for a band program.

The Cultural Blowback—and Counterarguments

Naturally, such a policy will meet resistance—not only from fans but from within. Band members may feel shortchanged on travel experiences. Alumni may bristle at what they see as a cultural dilution. Game promoters may worry about reduced ticket sales if the bands are not both present.

But it is precisely because bands matter so much that they should be protected from burnout and underinvestment. If leaving them home three or four times per year increases their overall budget, performance level, and recruitment reach, is that not a worthy trade?

Besides, culture evolves. Just as HBCUs have moved from AM radio to YouTube, from pamphlets to TikTok, so too can band culture adapt to a new hybrid reality—where physical presence is not the only measure of visibility or power.

A Conference-Wide Model: The SWAC and MEAC Could Lead

If this is to be implemented, it would ideally not be school by school, but as a conference-wide reform. Both the Southwestern Athletic Conference (SWAC) and the Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference (MEAC) could establish guidelines that limit band travel to key games while preserving equity among member institutions.

Such a policy might include:

- A rotating system where each team brings its band to only half of its away games;

- Revenue-sharing from livestreamed halftime performances;

- Incentives for home teams to offer cultural hospitality to offset the absence of the visiting band.

It would also open new possibilities for sponsorship. Corporate partners who understand the influence of HBCU bands could be enlisted to underwrite digital halftime content or band scholarships—an easier pitch if funds are not being spent on transport and logistics.

March Differently, Spend Smarter

Culture is not weakened by strategy. In fact, when deployed wisely, it is made more resilient. Leaving the bands at home for select away games is not a betrayal of HBCU tradition—it is a restructuring of it to survive and thrive in a new era.

In a time when HBCUs are asked to do more with less, the question is not whether the bands should still matter. Of course they do. The question is whether they should have to march themselves into financial depletion to prove it.

Better to let them rest, regroup—and when they do appear, make it unforgettable.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.