“Revolution is based on land. Land is the basis of all independence. Land is the basis of freedom, justice, and equality.” – Malcolm X

Few institutions have carried the weight of controversy in American housing like the homeowners’ association (HOA). For much of the 20th century, HOAs were weaponized as a tool of institutional racism restricting African Americans from buying into White neighborhoods through deed covenants, enforcing exclusionary zoning, and serving as gatekeepers of generational wealth accumulation. The very mechanism of neighborhood governance became one more way African America was told “you do not belong.” Yet history has a way of flipping its instruments. The very structural force once used to keep us out may be one of the few institutional levers available to keep us in. As gentrification and predatory development rapidly encroach upon historically African American communities from Houston’s Third Ward to Atlanta’s West End, from Washington D.C.’s Shaw to New Orleans’ Tremé, the need for institutional tools of land sovereignty grows urgent. Civic associations, while noble, often lack teeth. It may be time for African American neighborhoods to rethink the HOA, not as a relic of exclusion but as a shield of survival.

Most African American neighborhoods today rely on civic clubs or neighborhood associations. These bodies are typically voluntary, underfunded, and lack the legal authority to enforce community decisions. They can advocate to city councils, organize block cleanups, and serve as a cultural glue, but when it comes to confronting a developer with millions in capital and legal teams, they are simply outgunned. Civic associations cannot foreclose properties when owners ignore rules or dues, build substantial war chests because dues are voluntary and non-enforceable, or control property transfers when long-time residents sell. This means that even when a neighborhood is organized and has strong social cohesion, it remains structurally weak in the face of predatory real estate activity. Developers exploit this weakness buying distressed properties, lobbying city officials for zoning changes, and rapidly altering the fabric of communities without consent.

Unlike civic clubs, HOAs are legally binding entities. When properly designed and governed, they give communities leverage that is otherwise impossible. The ability to foreclose ensures compliance and funding. If dues are unpaid, the HOA has a mechanism to protect the community’s collective interests. Mandatory dues create a stable revenue stream. A community with 200 homes each contributing $500 annually generates $100,000. Over five years, that becomes half a million which is enough to hire lawyers, challenge city zoning, and even purchase properties outright. This institutional capital transforms neighborhoods from reactive to proactive. HOAs can also insert right-of-first-refusal clauses, allowing them to buy homes before they go to outside investors, preventing predatory acquisitions and allowing neighborhoods to decide who their neighbors will be and what developments fit the collective vision. Rules around property maintenance, density, and usage can prevent developers from converting single-family homes into high-turnover rentals or Airbnbs. These standards are not just about aesthetics they are about protecting neighborhood identity and safety.

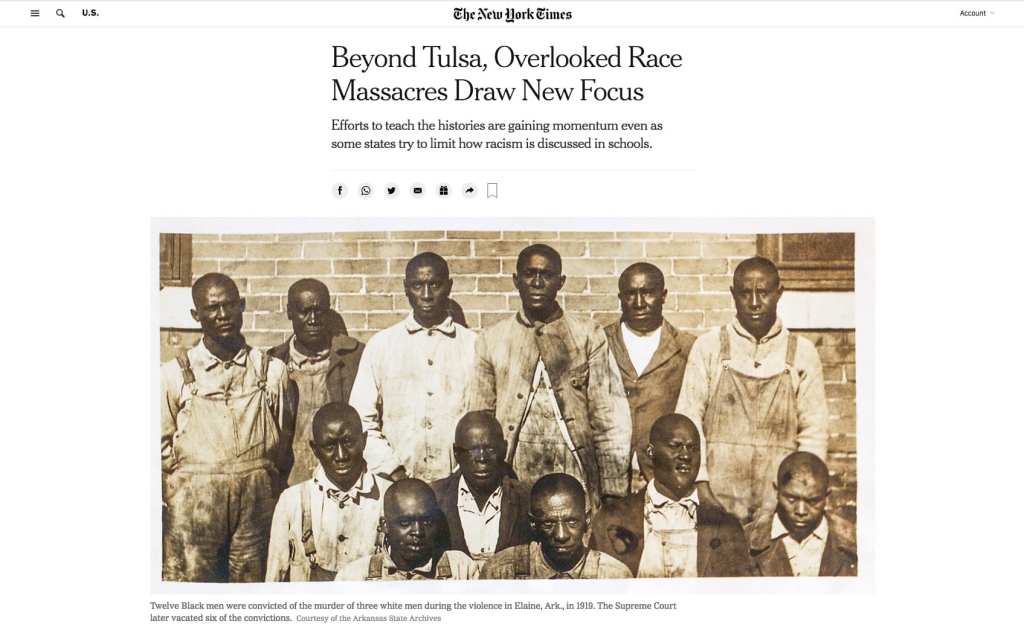

To advocate HOAs for African American communities is not to ignore their history. For decades, HOAs were bastions of exclusion. They operated in tandem with banks, appraisers, and city planners to enforce segregation. Deed restrictions openly barred African Americans and other minorities from ownership. Even when those covenants became unenforceable after Shelley v. Kraemer (1948), HOAs found new ways to enforce segregation through indirect mechanisms. But history also shows how institutions can be repurposed. Universities once denied African Americans; now HBCUs are among our strongest institutions. Banks once denied us credit; now Black-owned banks serve as pillars of community capital. The HOA, when reimagined under African American sovereignty, can become not a wall keeping us out, but a fortress keeping us in.

Houston’s Third Ward is emblematic. A historically Black neighborhood anchored by Texas Southern University, it has been ground zero for gentrification. Developers like TPC Endeavors LLC have defied city red tags, continued illegal construction, and ignored deed restrictions designed to protect single-family character. Residents organized, called 311, attended City Council meetings but the civic tools they had were insufficient. Enforcement by the city was lax. Meanwhile, developers were renting red-tagged properties as Airbnbs. Imagine if Third Ward had a robust HOA structure. With mandatory dues, it could hire legal counsel to file injunctions. With right-of-first-refusal, it could have purchased properties neighbors wished to sell, keeping them out of speculative hands. With codified rules, it could have legally enforced single-family restrictions, protecting housing stock for families rather than transient rentals. Instead, the community is stuck fighting asymmetrical battles, people with civic will against people with institutional power. The outcome, absent intervention, is predictable: displacement.

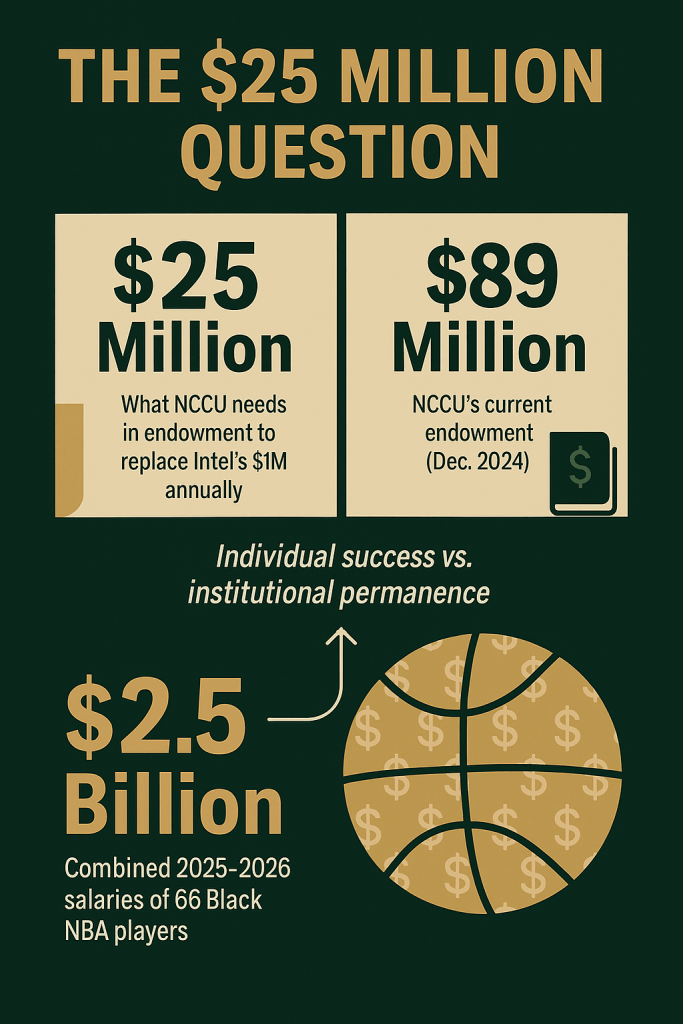

At its core, the case for African American HOAs is about institutional economics, the accumulation of collective capital to withstand systemic pressures. The median net worth of White households is nearly eight times that of Black households. Real estate is the largest component of wealth for African American families. When neighborhoods gentrify, this wealth is not preserved; it is extracted. HOAs serve as protectors of that capital by stabilizing community land values under African American governance. They enable neighborhoods to pool financial and legal resources to resist external exploitation. They foster long-term family residence, giving children environments with consistent community standards, building social and cultural capital alongside financial wealth. HOAs also enable neighborhoods to act like firms: they can engage developers on their own terms, negotiate concessions, or even partner in development deals that align with community interests.

Of course, HOAs are not a panacea. Poorly run HOAs can become abusive or corrupt, mirroring the very forces they are meant to resist. Mandatory payments can strain low-income residents, though creative structures such as sliding scales, subsidies, or partnerships with HBCUs and community foundations can mitigate this. Forming an HOA requires legal expertise and state recognition, which many African American communities lack immediate access to, though partnerships with HBCU law schools could be a solution. Neighborhoods may resist HOAs due to historical mistrust or fear of bureaucracy. Education campaigns and transparent governance are crucial.

The HBCU ecosystem has a unique role to play. Many HBCUs are surrounded by historically Black neighborhoods now under siege from gentrification. These institutions could provide the technical, legal, and financial scaffolding for community HOAs. Law schools could draft HOA charters and litigate against predatory developers. Business schools could train HOA boards in financial management. Architecture and urban planning programs could design neighborhood development standards. University endowments could provide seed capital to help HOAs acquire distressed properties. If HBCUs become the backbone of HOA development, they transform from being passive neighbors to active protectors of Black land sovereignty.

Imagine a network of African American HOAs across the country, each tied to local HBCUs, each building collective war chests, each controlling neighborhood development. Together, they form a patchwork of institutional sovereignty one block at a time, one neighborhood at a time. This is not just about resisting gentrification. It is about reclaiming agency over land, the foundational asset of all wealth and power. Without land sovereignty, African American communities will forever be tenants in someone else’s design. With HOAs, we have the chance to rewrite that story.

While HOAs have been historically tainted by their role in exclusion, African America must confront a hard truth: institutional problems require institutional solutions. Civic will, without institutional teeth, cannot withstand predatory capital. HOAs, properly structured and governed, give our neighborhoods enforcement power, financial capacity, and development control. Land sovereignty is not optional; it is existential. Gentrification is not just about higher rents or new coffee shops, it is about the slow erasure of African American communities from the map. If we are to remain, to build intergenerational wealth, and to strengthen our institutional power, then we must be willing to use every tool available. The HOA may have once been a weapon against us. It can now be the fortress that protects us.

Model HOA Framework for African American Communities

1. Charter Outline

A. Name and Purpose

- Name: [Neighborhood Name] Community Land Trust HOA

- Mission: To preserve and protect African American homeownership, stabilize property values, and foster community-driven development.

- Objectives:

- Protect neighborhood land from predatory acquisition and gentrification.

- Maintain architectural and cultural integrity of the neighborhood.

- Build collective financial resources for legal, development, and maintenance initiatives.

- Empower residents with decision-making authority over neighborhood development.

B. Membership

- All property owners within the HOA boundary are automatically members.

- Membership is determined by the community.

- Voting rights are proportional to ownership, with one vote per property.

C. Governance Structure

- Board of Directors: 5–9 elected members serving staggered three-year terms.

- Committees:

- Finance & Investment Committee

- Architectural & Community Standards Committee

- Legal & Advocacy Committee

- Outreach & Education Committee

- Decision-making: Major decisions (property acquisition, legal action, development approvals) require a 2/3 majority vote of the board and approval by 50%+1 of voting members.

D. Covenants and Bylaws

- Rules governing property use, maintenance, and modifications.

- Right-of-first-refusal on property sales to maintain African American ownership and prevent predatory acquisitions.

- Restrictions on commercial rental operations (e.g., short-term rentals like Airbnb) unless approved by the board.

- Enforcement of community standards through fines, liens, and, if necessary, foreclosure.

2. Funding Structure

A. Mandatory Dues

- Base dues calculated per household (example: $500–$1,000/year depending on neighborhood size and needs).

- Sliding scale or hardship exemptions for low-income homeowners, with supplemental funding from foundations or HBCUs.

B. Special Assessments

- Imposed for extraordinary needs such as legal battles, property acquisition, or infrastructure repairs.

- Must be approved by majority vote of HOA members.

C. Reserve Fund / War Chest

- 25–30% of annual dues set aside into a reserve fund for long-term projects or emergency legal needs.

- Goal: Maintain liquidity to purchase at-risk properties and fund legal actions without delay.

D. Partnerships & Grants

- Collaborate with HBCUs, local Black-owned banks, and philanthropic foundations for technical and financial support.

- Seek grants specifically for community land trusts, anti-gentrification initiatives, or neighborhood revitalization.

E. The HOA Investment Fund

- Neighborhood Endowment: A portion of dues is invested to build a long-term community fund. This endowment can invest in local African American businesses, the stock market, or other vetted opportunities. Returns are used to subsidize senior citizens and low-income residents, provide relief during emergencies, and strengthen the HOA’s financial independence.

- Emergency Fund: A dedicated reserve for disasters, legal challenges, or community emergencies.

- Special Assessments: Levied for large projects (legal defense, infrastructure, property acquisition).

3. Enforcement Mechanisms

A. Fines and Liens

- Fines for non-compliance with HOA rules (maintenance, property use, etc.).

- Unpaid fines converted into liens that attach to the property.

B. Legal Authority

- Covenants provide authority to take legal action against violators, including:

- Enforcing property use restrictions

- Preventing unauthorized sales or rentals

- Challenging predatory development through court injunctions

C. Foreclosure

- In extreme cases of non-payment or serious violations, the HOA has the right to foreclose on the property to protect collective community interests.

- Requires board approval and due process, with transparency to all members.

D. Right-of-First-Refusal

- The HOA can purchase homes before they are sold to external buyers.

- Maintains neighborhood ownership continuity and allows control over development aligned with community goals.

4. Community Engagement and Education

- Regular town halls and workshops on:

- Financial literacy and collective wealth building

- Understanding HOA powers and responsibilities

- Recognizing predatory developers and speculative practices

- Partnerships with local HBCUs to provide pro bono legal clinics, urban planning advice, and leadership development for HOA board members.

- Volunteer committees for property upkeep, neighborhood beautification, and cultural preservation.

5. Oversight and Accountability

- Annual audits of finances by independent accountants.

- Mandatory annual reporting to members detailing:

- Income and expenses

- Property acquisitions

- Enforcement actions taken

- Development approvals or denials

- Board elections conducted transparently with all members notified in advance.

6. Strategic Objectives for Anti-Gentrification

- Property Acquisition Strategy

- Identify at-risk properties before they are sold to outside investors.

- Use reserve funds or special assessments to purchase and hold properties for resale to qualified African American buyers.

- Legal Defense Fund

- Maintain a portion of the war chest specifically for litigation against predatory developers and enforcement of zoning codes.

- Cultural and Architectural Preservation

- Set clear standards for renovations and new construction that reflect neighborhood heritage.

- Ensure that new development aligns with the neighborhood’s long-term vision and identity.

- Economic Empowerment

- Encourage local entrepreneurship and small business ownership within the HOA’s commercial spaces.

- Partner with HBCUs and Black-owned banks to provide financing, mentorship, and business support.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.