“I had crossed the line. I was free; but there was no one to welcome me to the land of freedom. I was a stranger in a strange land.” – Harriet Tubman

Race riots or rural reckoning? The answer lies beneath the surface—and often beneath the soil itself.

Was Red Summer Of 1919 Really About African America’s Land Ownership? In the blistering summer of 1919, the United States erupted in racial violence. From Washington, D.C. to Chicago, from Norfolk to Omaha, more than three dozen cities and rural towns across America were sites of bloodshed as white mobs attacked African Americans. Historians dubbed it the Red Summer, invoking both the color of blood and the communist fears of the era. To many, it was the culmination of racial tensions stoked by the Great Migration, post-war competition for jobs, and white anxiety over African American assertiveness. But a century later, a question lingers uncomfortably beneath the textbook explanations: was Red Summer not merely about urban unrest or racial animus but about land?

That question has returned with renewed urgency amid a growing reexamination of Black land ownership and its deliberate erosion over the past century. As calls for reparations echo louder, so too does the need to reassess the forces that helped decimate Black wealth and autonomy. In doing so, Red Summer becomes not merely a narrative of racist rage, but potentially the most violent chapter in a longer, quieter war – a war over land.

A Nation Within a Nation

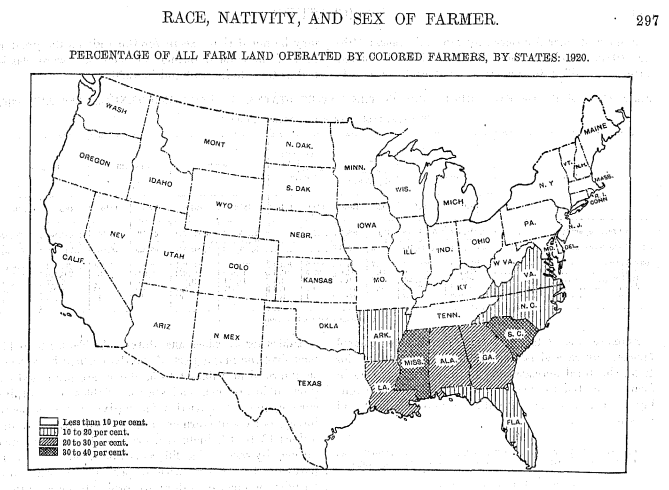

The idea that African Americans were only victims of economic exclusion in early 20th-century America is misleading. By 1910, African Americans owned more than 15 million acres of land, largely in the South. Black farmers, most of them formerly enslaved or their descendants, had managed to accumulate land under crushing odds frequently purchasing it collectively, through cooperatives, or from white landowners seeking to offload marginal plots. These holdings were not just symbolic. They were strategic.

Land ownership among Black Americans was more than a pathway to wealth; it was a bulwark against white supremacy. Land meant food security, political leverage, and a modicum of independence in a nation otherwise defined by dependency and domination. In some areas, land ownership translated into Black-majority townships or counties, Black-controlled economies, and the possibility however remote of a parallel sovereignty.

In other words, African Americans were not simply asking for equality; in some places, they were building it. And that may have been the greatest threat of all.

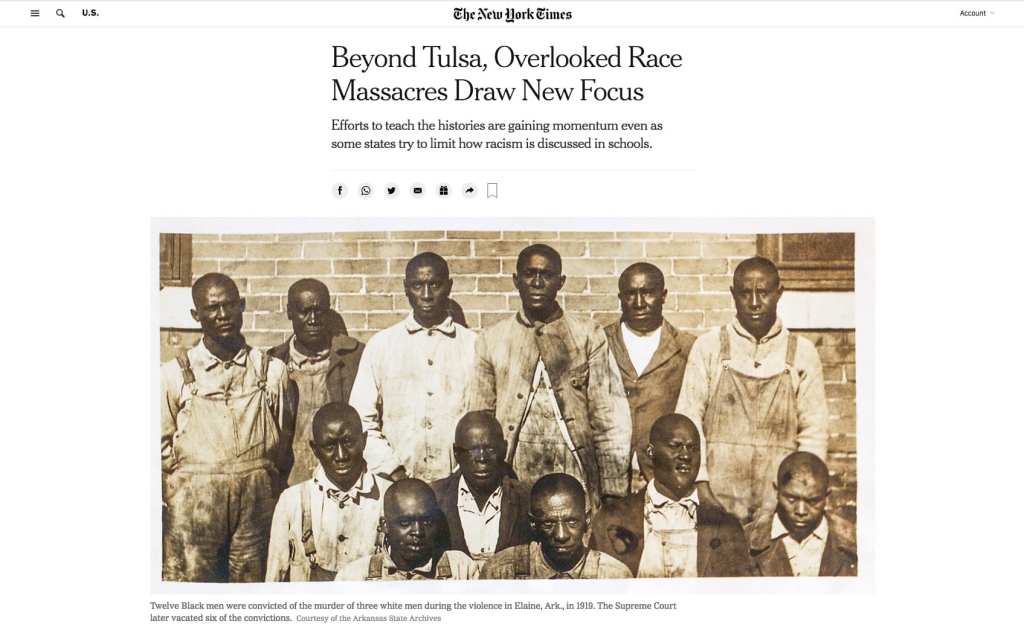

Elaine and the Sharecropper’s Revolt

Few episodes more clearly illustrate the link between land and lethal violence than the massacre in Elaine, Arkansas, one of the deadliest incidents of Red Summer. On September 30, 1919, African American sharecroppers organized a meeting in a church to form a union that would advocate for fair prices for their cotton crops. They were met with gunfire and a reign of terror. White mobs, backed by federal troops, killed an estimated 100 to 200 Black men, women, and children though official counts suggested only a few dozen.

The cause, according to white newspapers, was a Black uprising. But in reality, it was about economic control. The sharecroppers wanted transparency in accounting, freedom from rigged ledgers, and the ability to sell their cotton independently. The plantation economy, tightly controlled by white landowners, depended on the opposite. The fear was not Black rebellion it was Black negotiation.

The Elaine massacre exposed a hidden economic architecture. If Black farmers could collectively organize and access fair markets, they might become landowners themselves. And in the Delta, as elsewhere in the South, land was power.

Urban Unrest, Rural Intent

Though most Red Summer clashes are framed through an urban lens of riots in Washington, Chicago, and Knoxville, but the violence cannot be disentangled from broader efforts to confine Black advancement. Indeed, many urban migrants were themselves displaced farmers or sharecroppers whose land ownership efforts had been stymied, swindled, or burned out.

Take Chicago, where in July 1919, violence erupted after a Black teenager, Eugene Williams, accidentally drifted into a whites-only beach on Lake Michigan. What followed was a week of brutal violence that left 38 dead and hundreds injured. On the surface, the riot was sparked by a beach dispute. But deeper currents were at play. African Americans had begun moving into white neighborhoods, asserting their rights to live and invest in the North.

Property rights were again at the center. Black homeowners were increasingly seen as invaders. Redlining had not yet been formalized, but informal violence was already its precursor. The right of African Americans to own homes, build wealth, and control property even outside the South was met with hostility. In both city and countryside, Red Summer was a coordinated rejection of Black sovereignty, however modestly asserted.

White Fear of Black Autonomy

While land ownership by African Americans peaked around 1910, it was already declining by 1919. The reasons were manifold: discriminatory lending, racial violence, predatory legal schemes, and state-sanctioned dispossession. But Red Summer represents a psychological inflection point, the moment when white America responded not just to Black presence, but to Black self-determination.

The threat, as seen by many whites, was not just that Black people wanted civil rights. It was that they were seizing the mechanisms of wealth: land, capital, and cooperative enterprise. African Americans were not waiting for inclusion; they were building economic foundations outside the reach of white control.

This was especially threatening in the South, where many white families were still reeling from the Civil War, the collapse of slavery, and the erosion of the planter class. Black economic success particularly land ownership stood as both a rebuke and a warning. In this sense, Red Summer was not simply a racial backlash; it was a political counterinsurgency.

The Legal Infrastructure of Dispossession

What followed Red Summer was not a mere return to Jim Crow norms, but an intensification of efforts to eliminate Black landholding. A key tool was legal dispossession. Heirs’ property laws, in which land passed down without a will became jointly owned by all descendants, made Black land vulnerable to partition sales. White developers and speculators exploited these loopholes, often buying one family member’s share and forcing a sale of the entire property.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, African Americans lost 90% of their farmland between 1910 and 1997. Much of that was not merely through economic decline, but through coercive legal and extra-legal mechanisms: arson, lynching, and fraud.

Red Summer thus marked a gateway to systemic dispossession. In the decades that followed, the same violence that exploded in 1919 became bureaucratized: through zoning, lending discrimination, eminent domain, and legal chicanery.

Reparations and the Return to the Land

The lingering effects are visible in the data. Today, Black Americans own less than 1% of rural land in the United States. That figure stands in stark contrast to the 14% of the U.S. population that is Black. The wealth gap between Black and white families remains yawning, much of it attributable to the intergenerational transfer of property, land and home equity.

Reparations proposals have increasingly focused on this disparity. But to properly assess the scale of restitution, history must be rewritten to acknowledge not just the loss of life, but the loss of land. If Red Summer is reframed as a land war not only a race war, then it demands a different response.

Programs such as the Black Farmers Fund, the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, and the work of legal nonprofits like the Land Loss Prevention Project have begun to claw back some ground. Yet without a federal reckoning one that links racial violence to economic theft the narrative remains incomplete.

A Matter of Sovereignty

Land, as Malcolm X once noted, is the basis of all independence. Red Summer was not simply a spasm of postwar bigotry, but a calculated assertion of dominance over a people on the cusp of transformation. African Americans were not merely aspiring to equality; they were building sovereignty through land, labor, and law. The backlash was predictably violent. But violence, in this case, masked a deeper agenda: the eradication of a Black landowning class that threatened the racial and economic hierarchy. In the end, Red Summer may be remembered not only for its flames but for the fertile ground those flames sought to burn. It was not only a summer of blood. It was a war over soil.

📅 Visual Timeline: The Red Summer of 1919

April 13, 1919 – Jenkins County, Georgia

A violent confrontation erupts in Millen, Georgia, resulting in the deaths of six individuals and the destruction of African American churches and lodges.

May 10, 1919 – Charleston, South Carolina

White sailors initiate a riot, leading to the deaths of three African Americans and injuries to numerous others. Martial law is declared in response.

July 19–24, 1919 – Washington, D.C.

Racial violence breaks out as white mobs attack Black neighborhoods. African American residents organize self-defense efforts.

July 27–August 3, 1919 – Chicago, Illinois

The Chicago Race Riot begins after a Black teenager is killed for swimming in a “whites-only” area. The violence results in 38 deaths and over 500 injuries.

September 30–October 1, 1919 – Elaine, Arkansas

African American sharecroppers meeting to discuss fair compensation are attacked, leading to a massacre where estimates of Black fatalities range from 100 to 800.

October 4, 1919 – Gary, Indiana

Racial tensions escalate amid a steel strike, resulting in clashes between Black and white workers.

November 2, 1919 – Macon, Georgia

A Black man is lynched, highlighting the ongoing racial terror during this period.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.