We went from bartering to dollars. We can go from capitalism to whatever may come next. But without institutional ownership of the institutions that control the circulation of the medium, without the institutional ownership that protects our economic interest, and without the institutional ownership that reduces financial risk in our community, then power and empowerment will always be reduced to the fantasy of freedom we tell ourselves with raised fists. – William A. Foster, IV

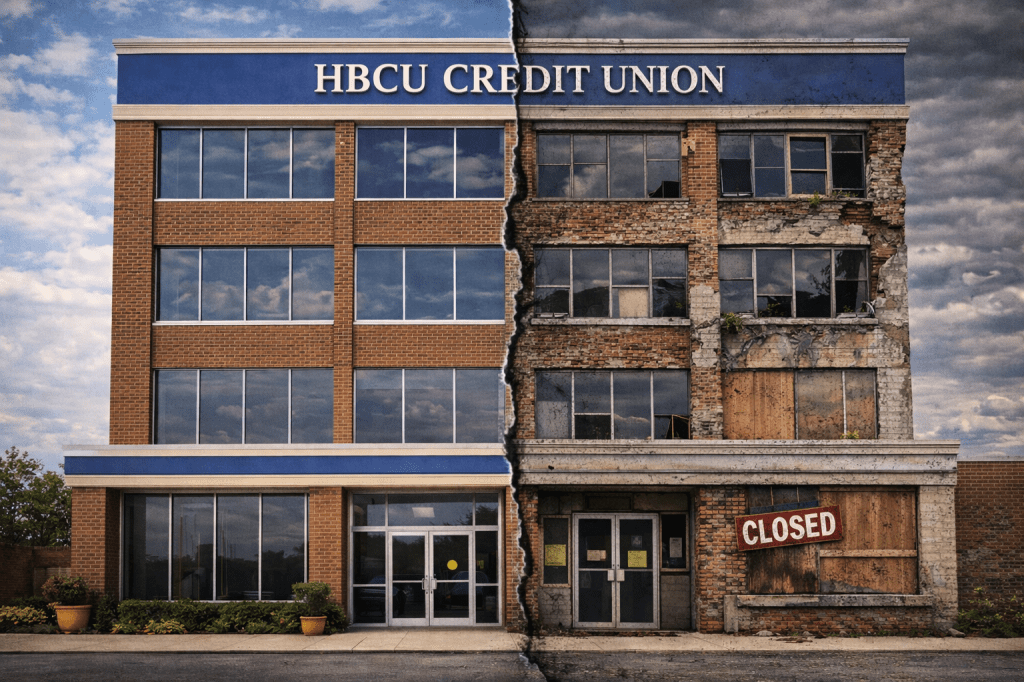

There is a financial story unfolding across the historically Black college and university landscape that is not receiving nearly enough attention. It is not a story about endowments, donor campaigns, or legislative funding fights — though it touches all of those. It is a story about credit unions: small, member-owned financial institutions that were once tethered to HBCUs as a gateway to financial inclusion for Black students, faculty, and alumni. One by one, they are disappearing. And the speed with which they have vanished over the past five years should alarm anyone who has spent even a passing moment thinking about African American wealth-building.

In 2020, HBCU Money published a comprehensive directory of all eleven HBCU-based credit unions in the country. The list was not long to begin with. Eleven institutions, spread across the nation, collectively holding $88.7 million in total assets and serving roughly 14,953 members. Those numbers were already modest bordering on fragile but they represented something tangible: a constellation of Black-controlled financial institutions with deep roots in the communities they served.

Today, that number has dropped to six.

Five HBCU-based credit unions have either closed or been acquired since that 2020 snapshot. Howard University Employees Federal Credit Union in Washington, D.C., which held $10.1 million in assets making it the fourth-largest in the group is no longer operational as an independent institution. Savannah State Teachers Federal Credit Union in Georgia, Tennessee State University’s credit union, and Shaw University’s federal credit union in Raleigh, North Carolina, the smallest of the group at just $400,000 in assets, have all ceased to exist as independent entities.

And then there is Prairie View A&M University Federal Credit Union, a case study in how these institutions disappear not with a clean closure, but with an acquisition that raises questions nobody seems willing to ask out loud. Prairie View FCU, which held $3.7 million in assets as of 2020, was absorbed by Cy-Fair Federal Credit Union, the credit union tied to Cypress-Fairbanks Independent School District in the Houston suburbs. Prairie View FCU now operates as a division of Cy-Fair FCU, retaining its name and its single location at the foot of the PVAMU campus but operating entirely under Cy-Fair’s infrastructure, branding, and control. The Cy-Fair FCU website frames the arrangement in the warmest possible terms celebrating PVFCU’s “remarkable 85-year history” and its founding in 1937 by sixteen pioneers who created a financial institution to serve employees of what was then Texas’s first state-supported college for African Americans. The language is reverent. The reality is that an 85-year-old Black institution, one built by and for a Black community, is now a subsidiary of a school district credit union. This in and of itself should be acutely embarrassing to the HBCU community. A school district lording over a higher education institution community’s financial interest.

The choice of Cy-Fair FCU as the acquiring institution deserves scrutiny. Cypress-Fairbanks ISD is the third-largest school district in Texas, but its relationship with its Black community has been, to put it charitably, troubled. In 2020, the district was forced to confront documented racial disparities in its own student discipline where African American students made up 18.5 percent of enrollment but accounted for 38.7 percent of suspensions in the 2018-19 school year. The district commissioned an equity audit, and the results confirmed what critics had long alleged: districtwide discrepancies in academics, discipline, and staff representation along racial lines. White students consistently outperformed Black peers on standardized tests and graduated at higher rates, while the teaching staff remained overwhelmingly white — 66 percent white in 2019-20, even as the student body had become far more diverse.

The situation reached a national flashpoint in January 2022 when Cy-Fair ISD trustee Scott Henry, who had won his seat on a platform centered on opposing critical race theory, made remarks at a board work session that were widely condemned as racist. Henry openly questioned the value of hiring more Black teachers, pointing to Houston ISD’s higher percentage of Black educators and linking it to that district’s dropout rate — a claim that multiple studies and education researchers have thoroughly debunked. Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo, then Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner, the NAACP, and the ACLU of Texas all called for his resignation. Henry was fired from his position at software company Splunk but, because he was elected, could not be removed from the board by his colleagues. His remarks, and the social media trail of racially charged posts that preceded them, painted a portrait of the ideological environment within Cy-Fair ISD’s governance.

It is into this environment that Prairie View FCU, an institution founded specifically to serve a historically Black university community was folded. The Cy-Fair FCU website does not dwell on any of this context. It offers a “Panther Card” debit card that channels a portion of spending back to PVAMU athletics, and it lists enhanced services like video banking and remote deposit. These are not trivial upgrades for an institution that previously lacked basic digital banking capabilities. But the upgrades come at a cost: Prairie View FCU’s independence, its board, and its autonomy as a Black-controlled financial institution are gone. What remains is a branding exercise — a name on a building, a division page on someone else’s website.

Five institutions, gone in roughly four years. What remains is a smaller, more concentrated group of survivors. According to 2025 data from the National Credit Union Administration, the six remaining HBCU-based credit unions now hold a combined $76.8 million in total assets and serve 11,588 members. Southern Teachers & Parents Federal Credit Union in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, leads the group at $28.9 million in assets. Florida A&M University Federal Credit Union in Tallahassee follows closely at $28.5 million. Virginia State University Federal Credit Union in South Chesterfield, Virginia, has seen meaningful growth, reaching $13.3 million in assets, a 54.4 percent increase since 2016. Councill Credit Union at Alabama A&M in Normal, Alabama, clocks in at $2.5 million, though it has lost roughly 28 percent of its assets over the same period. Arkansas A&M College Federal Credit Union in Pine Bluff holds $1.9 million, and Xavier University’s Credit Union in New Orleans, one of the smallest surviving institutions, manages $1.7 million.

The trajectory is not encouraging. Even among the survivors, total membership has declined by more than seven percent since 2016, dropping from 12,467 members to 11,588. The average assets per member across the group have risen — from $5,189 to $5,611 — but that figure is almost entirely a function of assets outpacing a shrinking membership base, not a sign of organic financial health or deepening engagement. These are institutions hemorrhaging members even as they struggle to grow. And that hemorrhaging did not catch everyone off guard. Back in February 2012, HBCU Money published a detailed proposal outlining a path forward for these credit unions — not as isolated, single-branch institutions stumbling through each academic year, but as a unified financial force. The concept was straightforward in theory: consolidate the eleven HBCU-based credit unions into a single national institution, or at the very least forge a formal alliance that would pool resources, share technology infrastructure, and create economies of scale.

The 2012 proposal painted a picture of what that consolidated institution could look like. With access to the combined workforce of HBCUs — roughly 180,000 full and part-time employees — along with approximately 400,000 students, over a million alumni, the endowments of more than a hundred institutions, and the financial ecosystems of the communities surrounding each campus, a unified HBCU credit union would have been one of the most significant African American-controlled financial institutions in the country. It would have had the scale to offer affordable mortgages, student loans, small business financing, and a suite of services that, individually, none of these credit unions could ever dream of providing.

That merger never materialized. The alliance was never formed. And the consequences of that inaction are now playing out in real time as institutions that might have been strengthened by consolidation instead fold into obscurity. The reasons for the failure are familiar and deeply structural. HBCU administrations have historically been risk-averse when it comes to financial innovation, partly because of the precarious funding environments many of these schools operate in, and partly because of a broader cultural reluctance to prioritize financial infrastructure as a strategic institutional asset. The credit unions themselves lacked the technological sophistication and institutional support needed to compete in a rapidly evolving financial services landscape. Many of them did not have functional websites, mobile apps, or even basic debit card programs, amenities that any modern financial institution would consider non-negotiable. As the 2020 directory noted, the most glaring deficiency was a lack of FinTech investment. Without it, these credit unions were structurally incapable of retaining members whose financial needs matured beyond what a single-branch, limited-service institution could offer.

To understand just how far behind HBCU-based credit unions have fallen, it helps to look at what a university-based credit union can become when it is given the institutional support, technological investment, and long-term strategic commitment to grow. Michigan State University Federal Credit Union — MSUFCU — is that example. And the comparison is, frankly, staggering. MSUFCU, headquartered in East Lansing, Michigan, is the largest university-based credit union in the world. Founded in 1937 by eight faculty and staff members — its earliest records were kept in a desk drawer, it has grown into a financial powerhouse that, as of 2025, serves over 367,000 members and holds $8.26 billion in assets. It operates out of more than 30 branches across Michigan, has expanded into the Chicago metropolitan area, and employs over 1,300 people. It is not just a credit union; it is a regional financial institution by any standard measure.

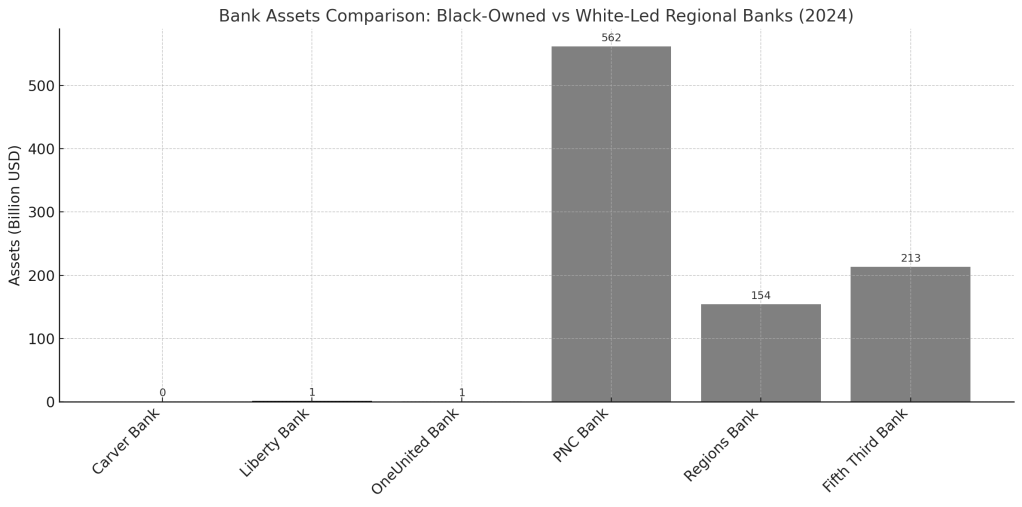

Put that number next to the combined assets of every African American credit union in the country including the six remaining HBCU-based credit unions and the disparity becomes almost difficult to articulate. The six surviving HBCU-based credit unions hold, collectively, $76.8 million in assets. MSUFCU holds $8.26 billion. That means a single predominantly white university credit union holds more than 107 times the combined assets of every HBCU-based credit union still in existence. MSUFCU’s assets are not just larger than the combined total of HBCU credit unions they exceed the total assets of virtually all African American credit unions in the country. The gap is not a crack. It is a canyon.

MSUFCU did not arrive at this scale through magic or accident. It grew because Michigan State University invested in it. It grew because the institution was given the runway to expand its membership base from employees to students to alumni and to build out the technological and physical infrastructure that a modern credit union requires. It grew because it had the institutional backing to pursue mergers and acquisitions, absorbing smaller credit unions and even banks as it expanded its geographic footprint. Every strategic move MSUFCU has made over the past several decades — the branch expansions, the technology partnerships, the acquisition of McHenry Savings Bank and Algonquin State Bank in the Chicago area — reflects a long-term institutional vision that HBCU-based credit unions have never had the support or the organizational will to pursue. The contrast is not merely about money. It is about institutional commitment. It is about whether a university sees its credit union as a strategic asset, a vehicle for building generational wealth among its community or as an afterthought, a small office on the edge of campus that serves a fraction of the student body and operates with minimal oversight and fewer resources.

The 2025 NCUA data on the six surviving HBCU-based credit unions tells a story of incremental progress layered on top of structural decline. Virginia State University Federal Credit Union is the clearest success story in the group, growing its assets by 54.4 percent since 2016 from $8.6 million to $13.3 million and increasing its assets per member by 87.1 percent, from $3,742 to $7,001. Florida A&M University Federal Credit Union has also seen solid growth, with total assets rising 41.3 percent to $28.5 million, and membership expanding by 16.5 percent to 3,918 members. But these gains are exceptions, not the rule. Southern Teachers & Parents Federal Credit Union in Baton Rouge, the largest in the group, has grown its assets by only 2 percent since 2016, and its membership has fallen by 15.6 percent, dropping from 5,124 members to 4,326. It is holding steady on assets while quietly bleeding its membership base. Councill Credit Union at Alabama A&M has seen its assets shrink by nearly 28 percent since 2016, and its membership has fallen by over 30 percent. Arkansas A&M College Federal Credit Union has lost 22.7 percent of its assets. Xavier University’s credit union has contracted by 36.3 percent in assets and lost 5 percent of its membership. Across the group, the median asset change since 2016 is negative 10.3 percent. The median membership change is negative 10.3 percent as well. For every Virginia State that is growing, there are two or three institutions quietly shrinking toward irrelevance.

The average assets per member across all six institutions now stands at $5,611, up from $5,189 in 2016. That is a 12.5 percent increase — a number that sounds encouraging until you consider that MSUFCU’s assets per member, calculated from its $8.26 billion in assets and 367,000 members, comes to approximately $22,500. HBCU credit union members hold, on average, roughly one-quarter of the per-member asset value that an MSU credit union member does. The wealth-building capacity of these institutions is simply not comparable.

The collapse of five HBCU-based credit unions between 2020 and 2025 is not an isolated event. It is a symptom of a larger pattern in African American financial infrastructure one in which institutions that could, in theory, serve as engines of wealth circulation and community investment instead wither from neglect, underfunding, and a failure of institutional imagination. The 2012 proposal for a consolidated HBCU credit union was not a radical idea. It was a practical one. Credit union mergers are common across the industry. MSUFCU itself has pursued multiple mergers and acquisitions as a core part of its growth strategy. The tools, the regulatory framework, and the precedent all exist. What has been missing is the will on the part of HBCU administrations, alumni networks, and the broader African American institutional ecosystem to treat financial infrastructure with the same urgency that is applied to endowment campaigns or facility renovations.

The #BankBlack movement that surged during the social justice awakening of 2020 brought renewed attention to African American financial institutions, including credit unions. But attention without structural investment is temporary. The members who were inspired to open accounts at HBCU credit unions during that period appear, in many cases, to have drifted away once the cultural moment passed, a pattern visible in the continued membership declines across the group.

If the remaining six HBCU-based credit unions are to survive and if the broader ecosystem of African American credit unions is to grow rather than contract the conversation must shift from nostalgia to strategy. That means revisiting the merger and alliance models that were proposed over a decade ago. It means demanding that HBCUs treat their credit unions as institutional priorities, not afterthoughts. It means investing in the technological infrastructure that members now expect as a baseline. And it means reckoning honestly with the fact that, while MSUFCU serves as an aspirational model, it did not build $8.26 billion in assets overnight. It built them over nearly ninety years of sustained, intentional institutional support.

The clock is not on HBCU credit unions’ side. The five that have already closed will not reopen. But the six that remain still hold something valuable: a foothold. The question is whether the institutions and communities they serve will invest in preserving it or whether the quiet collapse will simply continue, one credit union at a time, until there are none left to save.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ClaudeAI.