“It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.” — Aristotle

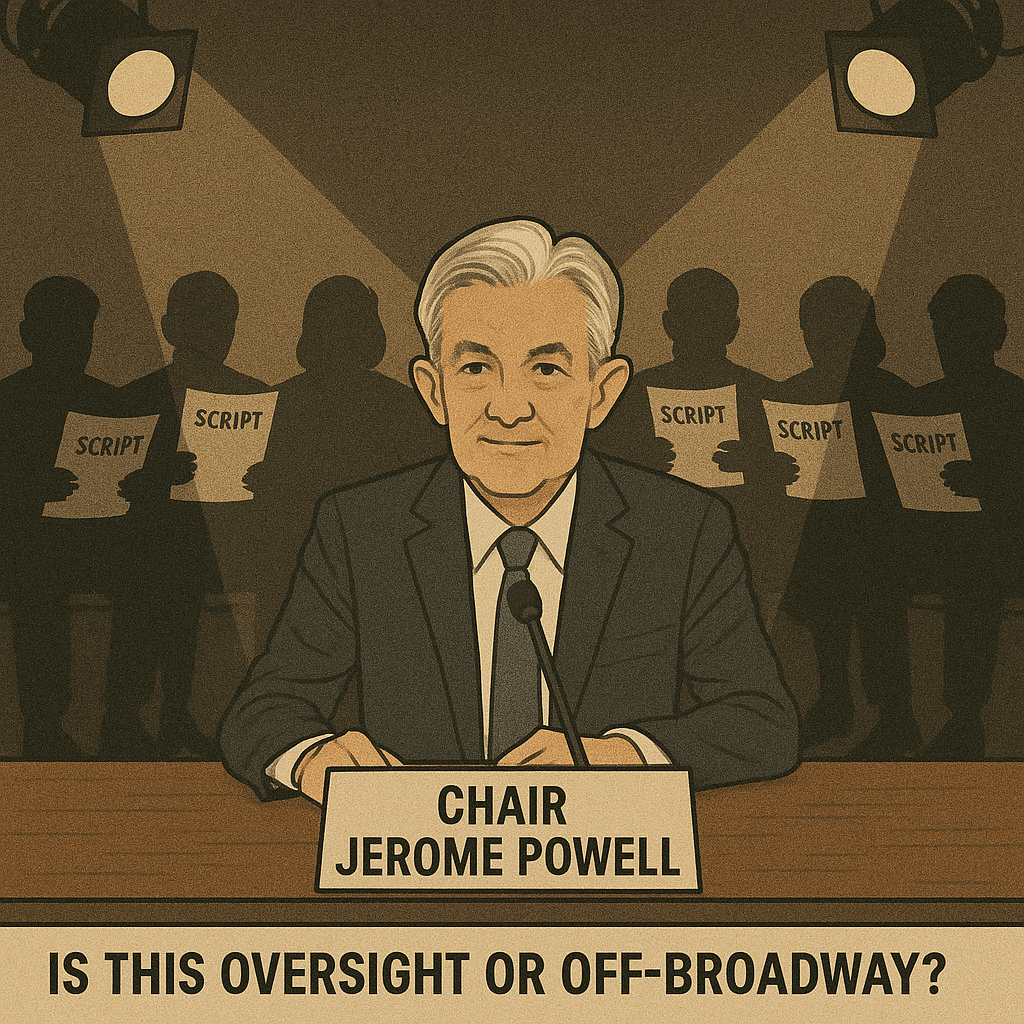

Each time Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell appears before Congress, particularly the House Financial Services Committee, a rare opportunity presents itself—one that could improve financial literacy at the highest levels of government and foster substantive dialogue on monetary policy’s profound impact on American households, businesses, and institutions. But that opportunity is almost always wasted.

Instead, the public is forced to endure yet another performance of political theater where elected officials, both Democrat and Republican, seem more concerned with going viral than going deep—more focused on five-minute gotchas than on fifty-year policy ramifications.

And for African America, whose economic institutions and family wealth face historic and systemic precarity, this continued dysfunction is not simply frustrating. It is dangerous.

The Purpose of Oversight or a Stage for Soundbites?

The Federal Reserve is arguably the most powerful economic institution in the world. Its chair, currently Jerome Powell, wields incredible influence over interest rates, inflation, labor markets, and the credit system. A hearing before Congress should be a time when policymakers probe deeply, ask sophisticated questions, and help inform the public through their own understanding.

Instead, what unfolds is often little more than ideological posturing. Members of Congress use their time to push personal or party agendas, cherry-pick statistics, or lob loaded questions with no intent of hearing the answer.

This isn’t oversight. It’s political performance art.

The House Financial Services Committee, charged with overseeing financial institutions, capital markets, and economic stability, must rise above this. Its role should be more than ceremonial. It should be educational—to itself and to the American people. But the overwhelming sense watching Powell’s recent testimonies is that most of the committee members lack even a basic understanding of how monetary policy functions, let alone how to interrogate it effectively.

Why It Matters for HBCUs and African American Economic Institutions

African America does not have the luxury of political and financial ignorance.

When inflation creeps higher, it isn’t just a line in a Bloomberg terminal. It is the difference between a Black student being able to afford books for the semester or choosing between groceries and tuition. It is a Black-owned small business having to lay off an employee because a loan’s interest rate jumped from 6% to 11%.

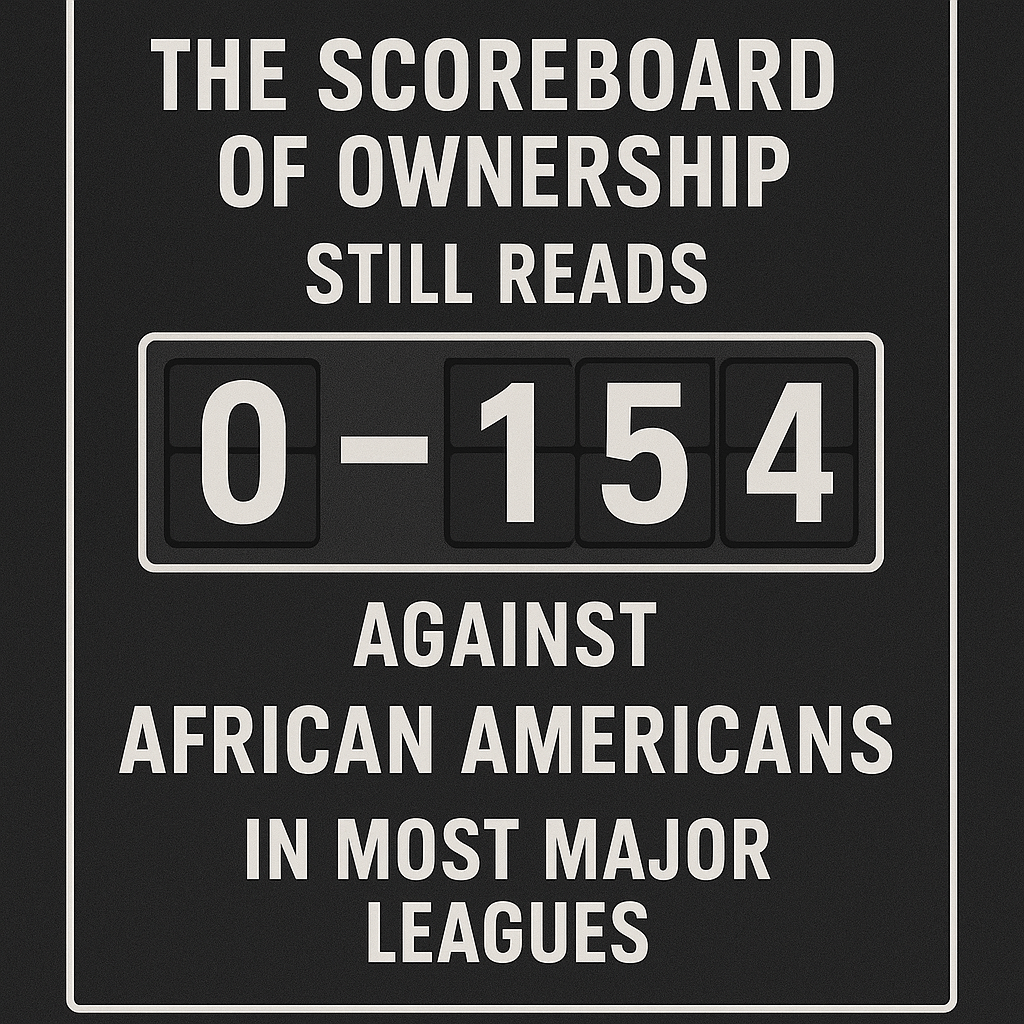

The lack of thoughtful interrogation of Powell’s monetary strategy reflects a more structural problem. There is a scarcity of African American economists in monetary policy circles. The Federal Reserve’s own ranks remain largely devoid of HBCU graduates, and few members of the House Financial Services Committee themselves come from economically marginalized backgrounds or have spent real time examining the consequences of macroeconomic policy on communities of color.

Yet these are the same communities most sensitive to interest rate swings, credit market freezes, or inflationary spikes.

And still, with this knowledge, Black America’s representatives—those on the committee and those adjacent—too often use their time during hearings for moral appeals or political slogans. But where is the policy meat? Where is the specificity? Where is the courage to press Powell on structural inequality in the Federal Reserve’s frameworks?

The Federal Reserve and the Myth of Neutrality

To be fair, the Federal Reserve, under Powell or any other chair, does not operate in a vacuum. But the institution often touts its political independence as a form of virtue. That independence, however, should not be mistaken for neutrality. The Fed’s policies have winners and losers.

From 2020 to 2022, the Fed’s monetary expansion saved financial markets—but also exploded asset prices, exacerbating wealth inequality. Homeowners gained equity. Renters fell behind. Banks consolidated more power while local lenders and community institutions—like Black banks—continued to struggle.

The committee could have questioned Powell on these outcomes. It could have demanded a racial wealth gap impact assessment of every major monetary policy decision. It could have interrogated how interest rate hikes disproportionately hurt historically marginalized borrowers. But those questions are never asked.

Instead, Powell is interrupted mid-sentence. Politicians talk over him. They make proclamations but ask no follow-ups. This behavior isn’t just disrespectful—it’s dangerous. And it’s a gross misuse of public time.

What HBCUs Can Teach Congress About Learning

At an HBCU, you learn that education is both a privilege and a weapon. It is something to be studied, sharpened, and used to build institutions. That approach—one rooted in discipline, humility, and preparation—is entirely missing from the House Financial Services Committee’s handling of monetary policy.

If a professor at Spelman or Howard or North Carolina A&T asked students to prepare a critique on central banking and one of those students responded with vague accusations or irrelevant political banter, they would be challenged to do better. Because rigor matters.

Imagine, instead, what would happen if HBCU economics departments had a seat at the table. Imagine if the committee regularly invited young scholars from Hampton, Morehouse, and FAMU to submit briefs or participate in Q&A sessions. Imagine a committee that used Powell’s visit as a chance to uplift new Black monetary scholars, who are often overlooked despite deep institutional knowledge.

There is no reason why an HBCU-trained economist should not be Chair of the Federal Reserve one day. But for that to happen, both access and expectation must change. We must expect more of Congress—and we must prepare ourselves to be in those seats.

The Price of Ignorance Is Paid in Communities Like Ours

Grandstanding doesn’t stabilize mortgage rates.

Political theater doesn’t ensure access to affordable credit.

Viral clips won’t help a Black farmer secure the funding needed to plant next season.

When the committee wastes its opportunity to genuinely understand and shape monetary policy, it abdicates responsibility for protecting those most vulnerable to economic volatility. Black communities cannot afford that negligence.

For instance, Powell was not questioned about how inflation-targeting might undervalue employment gains in Black communities. Nor was he asked whether the Fed’s models even consider racial employment disparities in real time. These are the kinds of questions that would surface if the committee viewed itself as learners—not performers.

A Call for Financial Statesmanship

What is needed in Congress is not just political courage but intellectual humility. An understanding that financial literacy is not just for constituents but must be a discipline practiced by lawmakers themselves.

The House Financial Services Committee could evolve into a place of high economic inquiry, a model of bipartisan dialogue around shared economic goals. But that will require members who read the footnotes of policy briefs, not just the headlines. Who consult experts across ideology. Who admit what they don’t know and ask better questions in return.

It also means creating a pipeline of informed staffers, many of whom should be HBCU-trained. Imagine a rotating fellowship where top students in finance and economics at Prairie View or Tuskegee serve one-year policy internships with members of Congress. Not only would this improve committee function, but it would democratize who gets to shape monetary discourse in the long run.

A Missed Opportunity That Cannot Keep Being Missed

Chair Powell is not infallible. His policies deserve scrutiny. But if the scrutiny is shallow, the Fed wins by default. Monetary policy deserves robust challenge—but that challenge must come with intellectual integrity, not political antics.

African American families, students, and business owners live with the real-world consequences of interest rate decisions every single day. They deserve elected officials who treat these hearings not as soundbite factories, but as classrooms—where hard questions are asked, where policies are dissected, and where the future is imagined more inclusively.

The Federal Reserve will always operate in the shadows unless Congress holds up a light. But to shine that light effectively, the House Financial Services Committee must first turn its cameras inward and ask whether it is performing or learning.

Because for communities like ours, the cost of their ignorance is far too high.