“Since new developments are the products of a creative mind, we must therefore stimulate and encourage that type of mind in every way possible.” – George Washington Carver

The 1890 Land-Grant HBCUs were created not out of generosity but from segregation. And yet, over 130 years later, these institutions have carved out vital roles in agricultural education, food systems innovation, and land stewardship within the African American community. With the ever-growing climate crisis, shrinking agricultural landholdings for African Americans, and a glaring need for sustainable economic engines, the case for a joint tree nursery among the 1890 HBCUs is less an idea and more an imperative. The time for silos is over. A joint nursery would allow the 1890s to consolidate resources, amplify research, and plant the seeds—literally and economically—of a new generational legacy.

The Decline of African American Landownership and Ongoing Discrimination

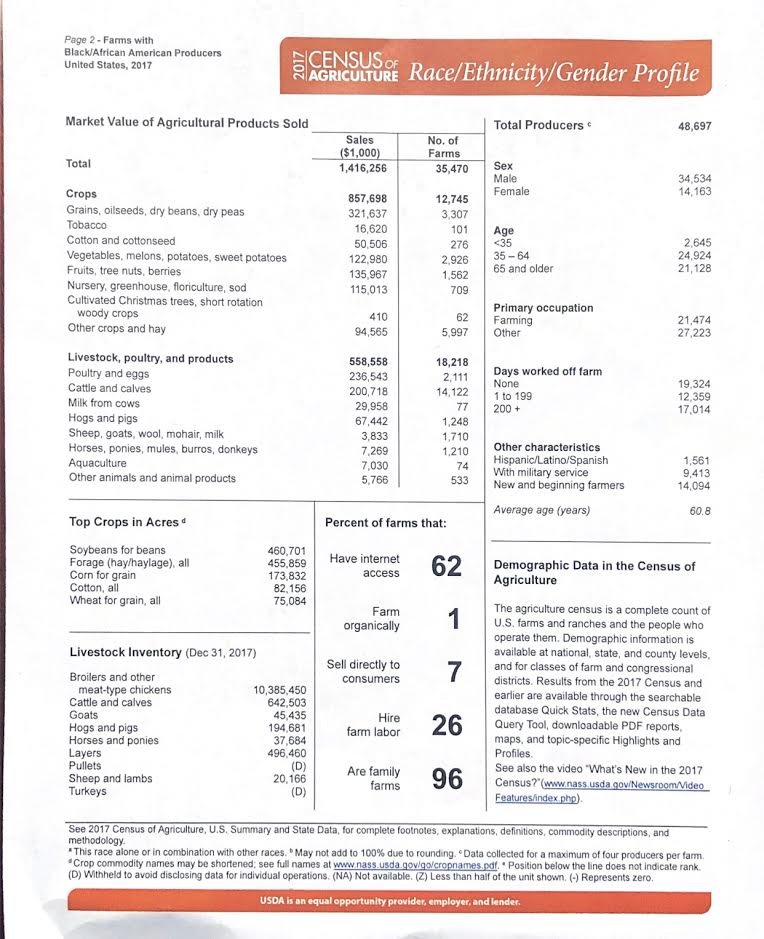

In 1910, African Americans owned between 16–19 million acres of farmland. The years around this period would also see the Red Summer of 1919, when African Americans were violently targeted and lynched—many as punishment for owning land and asserting agency. Today, that number has dwindled to just 5.3 million acres as of 2022, according to the USDA’s Census of Agriculture, representing less than 0.6% of all U.S. farmland.

The decline is not just the result of economic shifts—it is the result of orchestrated policies and racially motivated practices. From the USDA’s long-standing discriminatory loan denials to heirs’ property laws that have gutted intergenerational land transfer, the path of African American landownership has been riddled with legal landmines. The Pigford v. Glickman settlement acknowledged this in part, but much of the damage remains.

The 2022 USDA Census also shows that Black producers make up just 1.4% of all U.S. farmers and generate only 0.5% of all farm-related income. These are not just agricultural figures—they are a ledger of institutional neglect.

A tree nursery jointly stewarded by the 1890 HBCUs could serve as a bulwark against further erosion. It would offer seedlings, training, and enterprise development that support African American landowners, reinforcing land retention, sustainable usage, and intergenerational economic viability.

Political Hostilities Facing HBCUs

Despite their vital role in education, research, and community development, HBCUs—especially 1890 land-grant institutions—have faced persistent political and financial challenges. These institutions continue to experience disparities in state and federal funding compared to predominantly white institutions (PWIs). Some of the key political hostilities facing HBCUs include:

- Underfunding and Resource Disparities: Many 1890 HBCUs receive significantly less funding than their 1862 land-grant counterparts. Studies have shown that some states fail to allocate matching funds as required by federal law, putting HBCUs at a financial disadvantage.

- Legislative Attacks on DEI Initiatives: In recent years, political efforts to limit diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs have targeted HBCUs and other minority-serving institutions. These measures threaten scholarship opportunities, faculty recruitment, and student support services.

- Land-Grant Inequities: Unlike 1862 land-grant universities, 1890 HBCUs were historically excluded from receiving direct land allocations, resulting in fewer resources to develop agricultural research and extension programs. This inequity continues to hinder the growth of HBCU-led agricultural initiatives.

- Institutional Wealth Gap: A stark difference exists between the endowments of 1890 HBCUs and their 1862 counterparts. Many 1862 land-grant universities have endowments in the billions, while 1890 HBCUs often operate with significantly smaller financial reserves. This gap limits their ability to invest in infrastructure, research, and large-scale agricultural projects. By collaborating, 1890 HBCUs can leverage collective resources to overcome these financial disparities.

- Bureaucratic Challenges in Federal Funding: While the federal government provides grants and research funding for HBCUs, bureaucratic red tape often delays disbursement, limiting their ability to expand programs and infrastructure.

- Hostile Political Climates in Some States: Certain state governments have attempted to merge or close HBCUs under the guise of budget cuts, despite the institutions’ strong academic contributions. These efforts undermine the historical and cultural significance of HBCUs in providing equitable education.

By establishing a joint tree nursery, 1890 HBCUs can leverage collective power to secure funding, build partnerships, and showcase the tangible benefits of investing in Black-led agricultural and environmental initiatives.

Benefits of Developing a Joint 1890 HBCU Tree Nursery

Environmental Sustainability and Climate Change Mitigation

Deforestation and land degradation disproportionately affect African American communities, contributing to environmental injustices such as poor air quality and increased vulnerability to natural disasters. A joint tree nursery among all 1890 HBCUs would:

- Provide seedlings for reforestation projects in Black-owned lands and underserved communities

- Help mitigate climate change by sequestering carbon dioxide through afforestation and agroforestry initiatives

- Promote soil conservation and reduce erosion, particularly in the South, where agricultural practices have historically led to soil depletion

Economic Empowerment and Job Creation

A tree nursery initiative would not only benefit HBCU students and faculty but also offer economic opportunities to local landowners. Potential benefits include:

- Revenue Generation: HBCUs can sell tree seedlings to farmers, municipalities, and reforestation programs, creating an additional income stream

- Employment Opportunities: These nurseries can provide jobs for students, alumni, and community members in nursery management, forestry, and agribusiness sectors

- Support for Black Farmers: Providing affordable seedlings and training on agroforestry practices can help African American landowners diversify their income and maximize land productivity

The Economic Benefits of the Timber Industry

The timber industry presents a lucrative opportunity for African American landowners and HBCUs. A joint tree nursery can serve as a foundation for engaging in sustainable forestry and timber production. Some key economic benefits include:

- High Market Demand: The U.S. timber industry generates over $300 billion annually, with growing demand for sustainable wood products in construction, paper, and bioenergy sectors

- Long-Term Investment: Timberland is a valuable asset that appreciates over time, providing generational wealth-building opportunities for Black landowners

- Carbon Credit Market: African American landowners can participate in carbon credit programs by managing timberlands for carbon sequestration, receiving financial incentives for maintaining forests

- HBCU Forestry Programs: Expanding forestry education at HBCUs can produce a new generation of Black professionals in timber management, conservation, and agribusiness

- Sustainable Agroforestry: Integrating tree farming with traditional agriculture can enhance soil health, improve biodiversity, and create additional revenue streams for small-scale farmers

Enhancing Agricultural Education and Research

Many 1890 HBCUs already have robust agricultural programs. Establishing a joint tree nursery would further enrich their curricula by:

- Offering hands-on training in silviculture, agroforestry, and nursery management

- Creating research opportunities in sustainable land management, biodiversity conservation, and climate resilience

- Facilitating collaborations with government agencies, non-profits, and private sector partners in reforestation and urban greening initiatives

Cross-Institutional Leverage: Strength in Numbers

A joint venture allows for economies of scale. Rather than every 1890 HBCU creating a small, under-resourced nursery, a consortium-based model allows for regional specialization and centralized management. One school could lead genetic research, another logistics, and another economic modeling. By specializing within the larger system, each institution contributes to a whole far greater than its parts.

Shared governance would also model cooperative economics for students and landowners alike—an important lesson in collective power for African American institutions that have long been made to compete rather than collaborate.

Community Wealth Building

The ultimate beneficiaries of this nursery aren’t just students or the HBCUs themselves—but the millions of African American families with access to underutilized or at-risk land. With the right training, seedlings, and partnerships, that land can be revitalized. It can produce not only timber but herbs, fruits, shade, and carbon credits.

The nursery becomes the beginning of a longer story—of community land trusts, green business corridors, and intergenerational financial literacy built around land-based wealth.

Seeding Sovereignty: A Strategic Call to Action

Developing a joint tree nursery among all 1890 HBCUs is more than an agricultural endeavor. It is an act of economic strategy, cultural restoration, environmental justice, and institutional collaboration. It’s about controlling the seed, the soil, and the story.

HBCUs have always been tasked with doing more with less. The joint nursery is an opportunity to do more—together—and build an enduring institutional asset rooted in cooperation, conservation, and community wealth.

Moreover, this initiative holds symbolic power. In the act of planting trees, 1890 HBCUs will be planting legacy—sending a signal that African American institutions are prepared not only to survive hostile economic climates, but to thrive through collective will. Trees are not short-term investments; they require long-term vision, care, and commitment—just like the kind of intergenerational institution-building African America must embrace.

The nursery would also be an anchor institution for Black innovation in climate tech, agroforestry finance, and regional ecosystem services. The act of growing trees connects economics with ecology, and by anchoring that process within the halls and lands of 1890 HBCUs, we bring knowledge production, carbon markets, and green workforce development under African American institutional ownership.

This is more than sustainability—it is sovereignty. The type of sovereignty that rewrites narratives around Black land loss, economic disempowerment, and environmental marginalization. In a future where climate, capital, and culture will increasingly intersect, the 1890 HBCUs must see a joint tree nursery not as a boutique project but as a national imperative rooted in Pan-African strategy and local resilience.

The seeds of sovereignty are ready. The land is waiting. The only question is whether the institutions tasked with leading our communities into the future will plant now, or later—when the cost of delay may be too great to bear.