Let us never forget that government is ourselves and not an alien power over us. The ultimate rulers of our democracy are not a President and senators and congressmen and government officials, but the voters of this country. – President Franklin D. Roosevelt

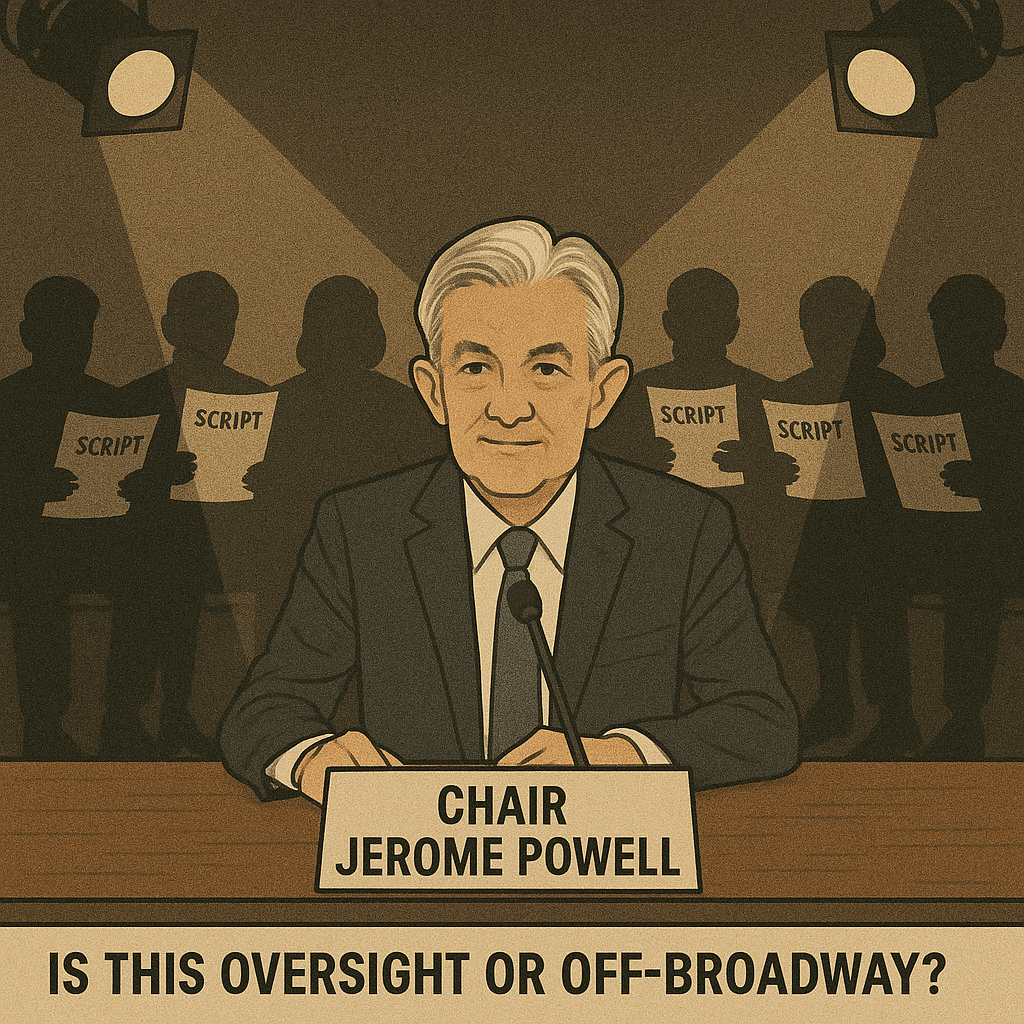

On January 11, 2026, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell delivered a stunning statement that crystallized a question many Americans may not realize they should be asking: Is the Federal Reserve the last major institution genuinely defending democratic principles in America?

Standing before cameras, Powell revealed that the Department of Justice had served the Fed with grand jury subpoenas threatening criminal indictment. The ostensible reason was his testimony to Congress about renovating Federal Reserve buildings. But Powell was direct about what was really happening: “This is about whether the Fed will be able to continue to set interest rates based on evidence and economic conditions or whether instead monetary policy will be directed by political pressure or intimidation.”

In that moment, the central bank of the United States became something more than a monetary policy institution. It became a test case for whether any American institution can resist President Trump’s political coercion over the next few years.

To understand why Powell’s statement matters, consider the landscape of American institutions today. The Supreme Court faces credibility challenges stemming from ethics controversies and a perceived ideological realignment. Congress operates in near-permanent partisan gridlock, struggling with basic functions like confirming appointments and passing budgets on time. State legislatures engage in aggressive gerrymandering and voting restrictions that challenge principles of equal representation. Executive power has expanded while norms of restraint have weakened across administrations.

Against this backdrop, the Federal Reserve maintained something increasingly rare: independence grounded in technical expertise and insulated from short-term political calculations. When President Trump repeatedly demanded interest rate cuts to boost the economy ahead of elections, the Fed held firm. When President Biden faced criticism over inflation, he publicly respected institutional boundaries. The Fed’s dual mandate of maximum employment and stable prices has required it to balance competing interests across the entire economy, forcing decisions that prioritize collective welfare over partisan advantage. Until now, that independence seemed relatively secure. Powell’s statement reveals it may be more fragile than Americans realized.

Powell’s January 11th statement is remarkable for several reasons. First, he explicitly connected the threat of criminal charges to the Fed’s monetary policy independence. He didn’t hide behind legal technicalities or bureaucratic language. He stated plainly that prosecution threats stem from the Fed “setting interest rates based on our best assessment of what will serve the public, rather than following the preferences of the President.” This is extraordinary transparency from an institution that typically communicates through carefully calibrated economic language. Powell used simple, direct terms: political pressure, intimidation, threats. He acknowledged that the ostensible reason for the subpoenas—his testimony about building renovations—was a pretext. He named what was happening.

Second, Powell invoked a principle larger than monetary policy: “Public service sometimes requires standing firm in the face of threats.” This isn’t the language of a central banker defending technical autonomy. It’s the language of someone defending an essential democratic principle, that institutions making decisions affecting all Americans should operate based on evidence and expertise, not political coercion. Third, Powell explicitly committed to continuing his work “with integrity and a commitment to serving the American people.” By framing his resistance as service to the public rather than institutional turf protection, he positioned the Fed’s independence as a democratic value rather than a technocratic privilege.

The Federal Reserve’s independence isn’t just about optimal interest rates or inflation targets. It represents a broader principle: that some decisions require insulation from short-term political calculations to serve long-term public welfare. When the Fed raises interest rates to combat inflation, it often creates short-term pain such as slower job growth, reduced business expansion, lower stock prices. Politicians facing elections have strong incentives to prioritize short-term stimulus over long-term stability. An independent Fed can make unpopular decisions that serve the country’s economic health over time.

This principle extends beyond economics. Independent courts can rule against popular sentiment to protect constitutional rights. Professional civil servants can implement policies based on expertise rather than political expediency. Scientists at government agencies can report findings that contradict administration positions. These institutional arrangements aren’t perfect, but they represent democracy’s attempt to balance popular sovereignty with expert judgment and long-term thinking. Powell’s statement suggests this balance is under direct assault, with the Fed potentially the last major holdout.

The Department of Justice subpoenas nominally concern Powell’s congressional testimony about Federal Reserve building renovations. Powell addressed this directly, noting that “the Fed through testimony and other public disclosures made every effort to keep Congress informed about the renovation project.” The suggestion that criminal charges might stem from routine congressional oversight testimony is itself remarkable, it criminalizes normal interaction between the legislative and executive branches. But Powell identified this as a pretext. The real issue is monetary policy that doesn’t align with presidential preferences.

This pattern using nominally legitimate legal mechanisms to pressure institutions making independent decisions represents a sophisticated form of institutional capture. It’s not crude interference like simply firing an agency head. It’s using the threat of criminal prosecution to reshape institutional behavior. The sophistication makes it more dangerous. It creates plausible deniability while achieving the same result: institutions become reluctant to make decisions contrary to executive preferences if doing so might expose their leaders to criminal investigation.

The Federal Reserve operates with more structural independence than most government institutions. Fed chairs serve fixed four-year terms that don’t align with presidential terms. Board members serve 14-year terms, ensuring continuity across administrations. The regional Federal Reserve bank structure distributes power geographically. These design features were intended to insulate monetary policy from political interference. If these protections prove insufficient—if the threat of criminal prosecution can bend the Fed to executive will then institutions with less structural independence have little chance of resisting similar pressure.

What happens to agencies making environmental regulations? To prosecutors deciding which cases to pursue? To intelligence agencies providing threat assessments? Democracy requires institutions that can tell truth to power. When the Environmental Protection Agency assesses climate risks, it needs to report findings honestly regardless of administration preferences. When the Congressional Budget Office scores legislation, it needs to provide accurate projections even if they contradict political claims. When courts rule on executive actions, they need to follow legal principles rather than political convenience. The Federal Reserve’s resistance to political pressure on monetary policy is part of this broader ecosystem of institutional independence. Its vulnerability suggests the entire ecosystem is at risk.

Jerome Powell cannot save American democracy alone. Even if the Federal Reserve maintains its independence on monetary policy, that doesn’t address court packing, voting restrictions, gerrymandering, or executive overreach in other domains. One institution resisting political capture doesn’t reverse broader democratic backsliding. Moreover, there are real tensions in celebrating the Fed as democracy’s guardian. The Federal Reserve is run by unelected officials making decisions with enormous consequences for ordinary Americans. Its most powerful body, the Federal Open Market Committee, operates with limited direct accountability. Unelected experts making consequential decisions without popular input can itself become anti-democratic.

The fact that we’re looking to an unelected central bank to defend democratic principles reveals how far other institutions have fallen. In a healthy democracy, Congress would check executive overreach, courts would protect institutional independence, and the civil service would resist improper political interference. That the Fed appears to be the last institution willing to publicly resist political coercion is an indictment of American governance, not just a testament to the Fed’s courage.

Powell’s statement creates several possible trajectories. The administration could back down (unlikely), recognizing that overtly criminalizing central bank independence would damage financial markets and America’s international credibility. Financial markets depend on confidence that U.S. monetary policy follows economic logic rather than political whim. International investors might flee dollar-denominated assets if they believe the Fed operates under political control. Alternatively, the administration could proceed with prosecution, testing whether public opinion, financial markets, or congressional action provide sufficient backstop to preserve Fed independence. This would transform an implicit crisis into an explicit constitutional confrontation. A third possibility is the subtler one: continued pressure without formal prosecution, creating uncertainty that gradually shapes Fed behavior. Board members might resign rather than face investigation. Future Fed chairs might be selected for political pliability. The institution might remain nominally independent while becoming practically captured.

The Federal Reserve’s independence ultimately depends on public support for the principle that some decisions should be insulated from short-term political pressure. Most Americans don’t follow monetary policy debates closely. But the principle that institutions should operate based on evidence rather than political coercion resonates beyond economics. Powell’s statement was unusually direct in part because he’s appealing beyond financial markets and policy experts to a broader public. He’s asking Americans whether they want institutions that can resist political intimidation or whether all government functions should answer directly to executive power.

This framing matters. If defending institutional independence becomes a partisan issue with one side supporting independent institutions and the other demanding political control then institutional independence has already lost. The Fed’s independence has survived because both parties recognized long-term benefits from monetary policy insulated from electoral cycles. Powell’s challenge is maintaining this bipartisan consensus at a moment when partisanship dominates and institutional norms have weakened.

There’s something appropriate in the Federal Reserve potentially becoming democracy’s last institutional defender. Central banks are unglamorous, technical, deliberately boring institutions. They don’t inspire passion or generate headlines under normal circumstances. They’re staffed by economists and lawyers making incremental decisions based on data and models. But democracy often depends on exactly these kinds of institutions. Not dramatic moments of resistance but everyday functioning of agencies that do their jobs professionally regardless of political pressure. Not heroic stands but consistent application of expertise and judgment independent of partisan considerations.

Powell’s statement was dramatic because it made explicit what usually remains implicit: that institutional independence requires constant defense, that political pressure is always present, and that resistance sometimes demands personal courage and public confrontation. The Federal Reserve may be the last institution defending these principles not because it’s special but because it’s one of the few with sufficient structural independence and public credibility to mount visible resistance. Its fight is everyone’s fight. If the Fed falls to political capture, the precedent suggests no institution is safe.

January 11, 2026 may be remembered as the day the question became explicit: Can American democratic institutions survive sustained pressure from political leaders willing to use criminal prosecution as a tool of institutional capture? Jerome Powell’s statement doesn’t answer that question. It simply acknowledges the question exists and declares his intention to resist. Whether that resistance succeeds depends on factors beyond the Federal Reserve—on Congress, courts, financial markets, public opinion, and the willingness of other institutional leaders to stand alongside the Fed in defending independence.

The Federal Reserve isn’t democracy’s savior. But in making public the political pressure it faces and explicitly refusing to capitulate, it’s doing what democratic institutions must do: operating based on evidence and principle rather than political intimidation. Whether other institutions find similar courage may determine whether American democracy survives its current crisis of institutional legitimacy. For now, the central bank stands. How long it can stand alone remains to be seen.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ClaudeAI.