“I built a conglomerate and emerged the richest black man in the world in 2008 but it didn’t happen overnight. It took me 30 years to get to where I am today. Youths of today aspire to be like me but they want to achieve it overnight. It’s not going to work. To build a successful business, you must start small and dream big. In the journey of entrepreneurship, tenacity of purpose is supreme.” — Aliko Dangote

It could be argued that many HBCUs do not see themselves as African American institutions. They just happen to be a college where African American students are the predominant student population – for now. A place where you may happen to find more African American professors than you would elsewhere. But in terms of intentionally being a place looking to serve the social, economic, and political interests of African America and the African Diaspora as a whole not so much. Schools like Harvard and the Ivy League in general seek to serve WASP interests, BYU and Utah universities serve Mormon interests, there is a litany of Catholic universities led by the flagship the University of Notre Dame serving Catholic interests, and around 30-40 women’s colleges serving women’s interests. Arguably, none are more intentional though than Jewish universities who seek to serve Jewish Diasporic interests. They do so intentionally and unapologetically. It is highlighted in two prominent dual programs.

Brandeis University, “founded in the year of Israel’s independence, Brandeis is a secular, research-intensive university that is built on the foundation of Jewish history and experience and dedicated to Jewish values such as a respect for scholarship, critical thinking and making a positive difference in the world.”

Master of Arts in Jewish Professional Leadership and Social Impact MBA In partnership with the Heller School for Social Policy and Management: “If you want to become a Jewish community executive, this program will give you the skills and expertise you need: a strong foundation in both management and nonprofit practices, as well as a deep knowledge of Judaica and contemporary Jewish life. You’ll take courses taught by scholars across the university, including management courses focused on nonprofit organizations and courses specific to the Jewish community.”

Master of Arts in Jewish Professional Leadership and Master in Public Policy: “If you want to become a professional leader who can effect positive change for the Jewish community at the policy level, you’ll need policy analysis and development skills as well as knowledge of Judaic studies and contemporary Jewish life — all of which our MA-MPP track is designed to impart. This track will teach you how to both assess policy and practice and design and implement strategic solutions.”

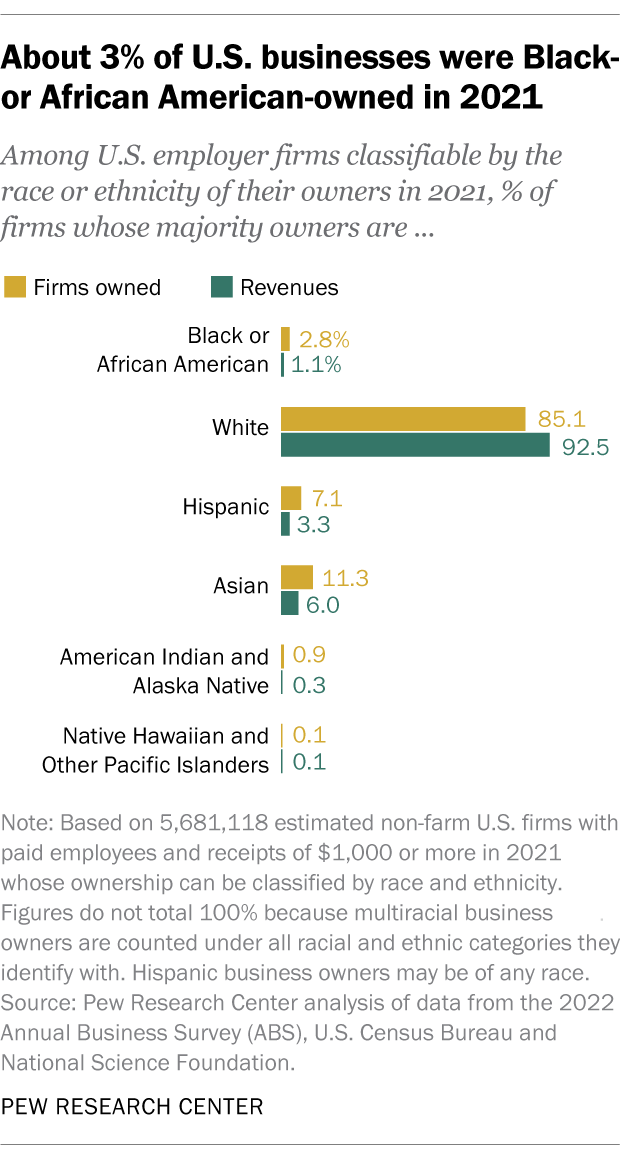

In the United States, the racial wealth gap remains stubbornly wide. For every dollar of wealth held by the average white household, the average Black household holds just 14 cents, according to the Federal Reserve. While policy debates rage on, a quieter revolution could be ignited in the lecture halls and boardrooms of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). It is time for these institutions to take the lead in launching a new kind of MBA—one rooted in African American entrepreneurship.

This would not be a symbolic gesture of representation. Rather, it would be a radical recalibration of business education in service of economic sovereignty. The proposed African American MBA, anchored at HBCUs, would fuse conventional business acumen with a deep focus on building and scaling Black-owned enterprises—injecting capital, credibility, and cultural context into the fight for economic justice.

A Different Kind of MBA

Traditional MBA programs—whether in Boston, Palo Alto, or London—have long celebrated entrepreneurship, but they rarely address the distinct structural barriers faced by African American founders: racialized lending, limited intergenerational capital, and investor bias, among others. An African American MBA would tackle these head-on.

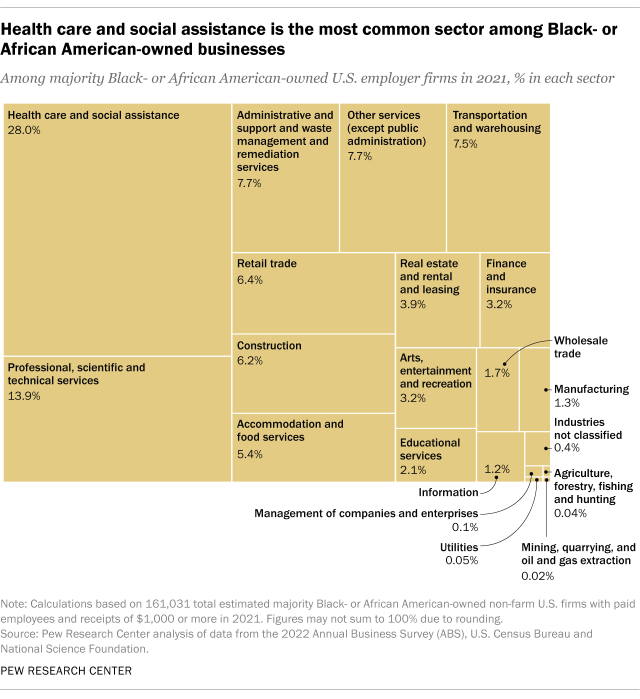

Students would learn to navigate venture capital ecosystems that have historically excluded them, build business models designed for resource-scarce environments, and craft growth strategies anchored in community reinvestment. The curriculum would include case studies of Black-owned business successes and failures, from the Johnson Publishing Company to the modern fintech startup Greenwood Bank.

Such a program would not just train entrepreneurs; it would cultivate what economist Jessica Gordon Nembhard refers to as “economic democracy”—an ownership-driven economy where Black communities produce and own the value they generate.

From Theory to Practice

For this model to work, HBCUs must go beyond coursework. They must build ecosystems.

At the core of the program would be university-based business incubators providing capital, mentorship, and workspace. Students could launch ventures with real funding—from alumni-backed angel networks or Black-owned community development financial institutions (CDFIs). Annual pitch competitions would create visibility and momentum, offering grants, equity investment, or convertible notes to top-performing student ventures.

A tight integration with Black-owned businesses, supply chains, and financial institutions would form the scaffolding. Students might spend time embedded in legacy enterprises like McKissack & McKissack, or cutting-edge startups in healthtech, agritech, and media.

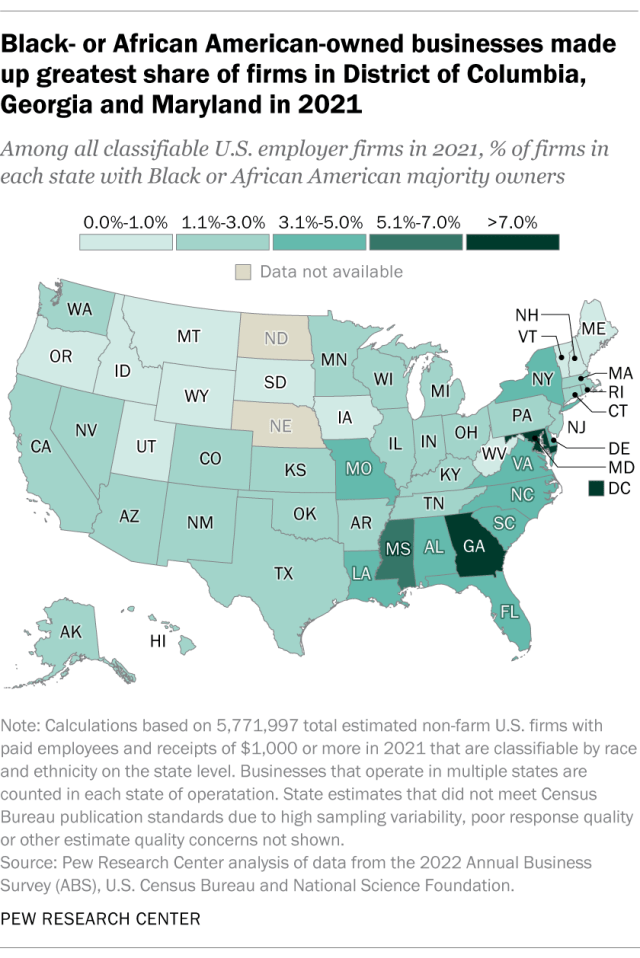

These ecosystems would provide fertile ground for venture creation while catalyzing local job growth. In doing so, they would re-anchor HBCUs as engines of regional economic development, not just academic training grounds.

The HBCU Edge

HBCUs are uniquely positioned to own this space. They already produce 80% of the nation’s Black judges, half of its Black doctors, and a third of its Black STEM graduates. Yet despite this outsized impact, their business schools have yet to consolidate around a unifying purpose.

By championing entrepreneurship explicitly tailored to African American realities, HBCUs could claim a domain left underserved by Ivy League and flagship public institutions.

Moreover, HBCUs benefit from strong community credibility, a network of engaged alumni, and access to philanthropic capital increasingly earmarked for racial equity. With ESG mandates guiding corporate philanthropy and DEI budgets under scrutiny, there is untapped potential for long-term partnerships with companies seeking measurable social impact through supplier diversity, mentorship, or procurement commitments.

Risks and Realities

Skeptics will ask: Will such a degree be taken seriously in the broader market? Will it pigeonhole students into “Black businesses” instead of the Fortune 500? The answer lies in the performance of the ventures it produces. Success, not symbolism, will be the ultimate validator.

Indeed, many of the world’s most transformative businesses have emerged from institutions that bet on community-specific models. Consider how Stanford’s proximity to Silicon Valley allowed it to incubate global tech companies—or how Israel’s Technion helped power a startup nation.

An African American MBA need not limit its graduates to one demographic. Rather, it provides a launchpad from which Black entrepreneurs can build scalable, inclusive ventures rooted in lived experience. And in doing so, change the face of entrepreneurship itself.

The Road Ahead

If a handful of HBCUs lead the way—Howard, Spelman, North Carolina A&T, and Texas Southern come to mind—they could collectively establish a national center of excellence for African American entrepreneurship. Over time, this could grow into a consortium offering joint degrees, online programming, and cross-campus business accelerators.

The long-term vision? A Black entrepreneurial ecosystem rivaling that of Cambridge or Palo Alto, but infused with the resilience, cultural currency, and social mission uniquely forged by African American history.

This would not merely be an academic experiment. It would be a new chapter in a centuries-old story—one where the descendants of slaves become the architects of capital.

Focusing an African American MBA program offered by HBCUs on entrepreneurship could be transformative for fostering economic growth and self-sufficiency within the Black community. Here’s how such a program might look:

Program Vision and Goals

- Empower Black Entrepreneurs: Equip students with the tools and networks to build successful businesses that create wealth and opportunities within African American communities.

- Address Systemic Barriers: Focus on overcoming challenges like access to capital, discriminatory practices, and underrepresentation in high-growth industries.

- Build Community Wealth: Promote entrepreneurship as a pathway to closing the racial wealth gap and revitalizing underserved areas.

Curriculum Highlights

Core MBA Foundations:

- Finance for Entrepreneurs: Teach how to secure funding, manage cash flow, and create financial models tailored to African American small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

- Marketing and Branding: Strategies for building culturally relevant brands that resonate with diverse audiences.

- Operations and Scaling: Guidance on running efficient operations and scaling businesses sustainably.

Specialized Courses:

- Tomorrow’s Entrepreneurship: Building ventures with dual goals of profit, community impact, and focus on industries of the future.

- Navigating VC and Angel Investments: Training on pitching to investors, negotiating terms, and understanding equity structures.

- Black-Owned Business Case Studies: Analyze successes and failures of prominent African American entrepreneurs. Much like the Harvard Business Review that sells case studies there would be an opportunity for HBCU business schools to create a joint venture for the HBCU Business Review and sell case studies relating to African American entrepreneurship.

Hands-On Experiences

Business Incubator:

- A dedicated incubator at the HBCU to provide seed funding, mentorship, and workspace for students to develop their ventures.

Real-World Projects:

- Partner students with local Black-owned businesses to solve real business challenges.

Annual Pitch Competitions:

- A platform for students to showcase business ideas to potential investors, with prizes and funding opportunities.

Partnerships and Networks

Corporate and Community Collaborations:

- Partnerships with companies that prioritize supplier diversity programs to provide procurement opportunities for graduates.

- Collaborations with established Black entrepreneurs for mentorship and guest lectures.

Access to Capital:

- Establish a dedicated fund or partnership with Black-owned financial institutions to provide startup capital.

Measurable Outcomes

- Startups Launched: Track the number of new businesses started by graduates.

- Jobs Created: Measure the economic impact of those businesses in local communities.

- Community Investment: Monitor how much revenue is reinvested into underserved neighborhoods.

In contrast to institutions that intentionally serve specific cultural, religious, or ideological communities, many HBCUs appear to operate as predominantly African American in demographic composition rather than as institutions deeply invested and intentional in advancing the collective social, economic, and political interests of African Americans and the African Diaspora. While other universities—whether Ivy League institutions catering to elite WASP traditions, religious universities fostering faith-based leadership, or Jewish universities purposefully cultivating Jewish communal leadership—explicitly align their missions with the advancement of their respective communities, HBCUs often lack this same level of strategic intent. If HBCUs wish to remain vital and relevant in the future, they may need to more deliberately embrace their role as institutions committed to the upliftment of African American communities, not just as spaces where Black students and faculty are well-represented, but as powerful engines of social transformation.