Our credit system, like almost institutional reality we have is very much dependent on Others. Until we realize and work towards infrastructure of our own institutional ownership within the credit landscape, then we will continue to be prey for predators and subsidizers that enriches others and their institutions. – William A. Foster, IV

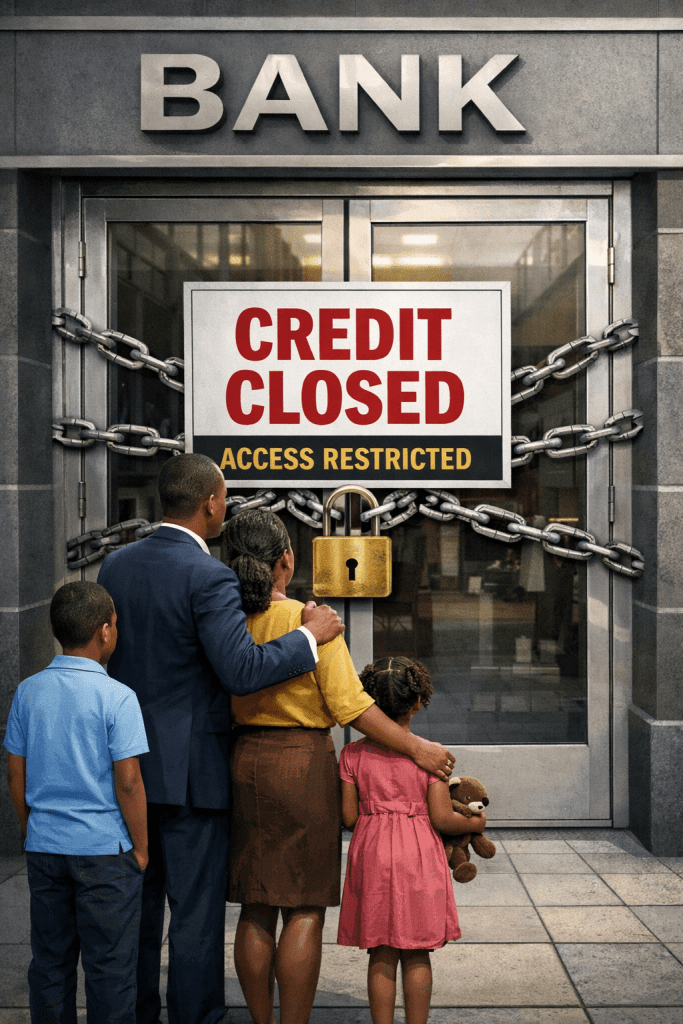

When President Donald Trump announced a proposed 10% cap on credit card interest rates in January 2026, most Americans greeted the news with skeptical hope. The move seemed like a potential lifeline for families struggling with debt burdens and interest rates that often exceed 20%, even as many questioned whether it could actually happen. But for African American households, this well-intentioned policy could become another barrier in a financial system that has historically excluded and disadvantaged them.

The challenge lies not in the intention behind rate caps, but in their likely consequences. While lower interest rates sound beneficial on the surface, the economic reality of credit markets means that banks facing reduced profitability will respond by restricting who can access credit in the first place. For African American families already fighting against systemic barriers to financial services, this could close doors that were only partially open to begin with.

African American households face dramatically different credit market realities than their white counterparts. According to the FDIC’s 2023 survey, more than 10% of Black Americans lack access to basic checking or savings accounts, compared to just 2% of white Americans. This banking gap represents more than inconvenience it fundamentally limits the ability to build the credit history that determines access to affordable loans, mortgages, and yes, credit cards.

The wealth disparity tells an even starker story. The median net worth of white households stands at approximately $188,200, nearly eight times the $24,100 median for Black households. This gap isn’t accidental it’s the product of generations of discriminatory policies from redlining to predatory lending, compounded by the deterioration of African American-owned banks and credit unions. As Black ownership of financial institutions has declined, the community has become more reliant on external institutions for credit, creating conditions that invited more predatory lending into African American neighborhoods. When African Americans do access credit, they consistently face higher interest rates than white borrowers with similar incomes. High-income Black homeowners, for instance, receive mortgage rates comparable to low-income white homeowners.

The dependence on consumer credit has reached critical levels in African American households. Recent analysis from HBCU Money’s 2024 African America Annual Wealth Report reveals that consumer credit has surged to $740 billion, now representing nearly half of all African American household debt and approaching parity with home mortgage obligations of $780 billion. This near 1:1 ratio between consumer credit and mortgage debt represents a fundamental inversion of healthy household finance. For white households, the ratio stands at approximately 3:1 in favor of mortgage debt over consumer credit. The African American community stands alone in this precarious position, where high-interest, unsecured borrowing rivals the debt secured by appreciating assets.

These disparities matter enormously when considering how banks will respond to rate caps. Credit card companies operate on risk-based pricing models, charging higher rates to borrowers they perceive as riskier based on credit scores, income stability, and banking relationships. African American borrowers, because of structural disadvantages in each of these areas, already cluster in categories that receive higher interest rates. When banks can no longer charge those rates, they will simply stop offering credit to these borrowers entirely.

The banking industry’s response to Trump’s proposal has been swift and unequivocal: a 10% interest rate cap would force them to dramatically restrict credit availability. Analysis from the American Bankers Association suggests that nearly 95% of subprime borrowers, those with credit scores below 680 would lose access to credit cards under even a 15% cap. With rates currently averaging around 20%, a 10% ceiling would affect even more borrowers. Industry analysts estimate that between 82% and 88% of credit cardholders could see their cards eliminated or their credit limits drastically reduced. The Electronic Payments Coalition warns that low to moderate income consumers would be hit hardest, precisely the demographic where African American households are disproportionately represented.

This isn’t just industry fearmongering. Historical evidence supports these concerns. When Illinois implemented a 36% APR cap on all borrowing, lending to subprime borrowers plummeted. Similar patterns emerged from 19th-century usury laws and research on payday loan restrictions. The consistent pattern is clear: when rate caps make lending unprofitable, lenders exit the market or tighten requirements. For African American households, this creates a devastating catch-22. They’re more likely to need credit due to lower wealth levels and less access to family financial support. Yet they’re also more likely to be denied that credit or pushed into predatory alternatives when traditional sources dry up.

The credit card industry categorizes borrowers by risk, with subprime borrowers facing the highest rates but also the greatest need for access to credit. African American consumers are overrepresented in subprime categories, not because of personal failing but because of systemic factors that suppress credit scores. Historical discrimination in housing, employment, and lending created wealth gaps that persist through generations. Lower wealth means less ability to weather financial shocks, leading to missed payments that damage credit scores.

When major banks stop serving subprime borrowers, those families don’t suddenly stop needing credit. They turn to alternative sources and here’s where the rate cap could cause real harm. Payday lenders, pawn shops, auto title loans, and other fringe financial services often charge effective annual percentage rates far exceeding credit card rates, sometimes reaching 300% to 400% or higher. These services operate in a less regulated space where consumer protections are weaker and predatory practices more common.

African American neighborhoods already contain disproportionately high concentrations of these alternative lenders, a modern echo of historical redlining patterns. Bank branches are scarce in many predominantly Black communities, while check-cashing outlets and payday loan storefronts proliferate. A rate cap that drives more families into this unregulated market would exacerbate existing inequities. The irony is profound. A policy designed to protect consumers from high interest rates could push vulnerable families toward even higher costs and fewer protections. JPMorgan analysts warned that the rate cap could redirect borrowing away from regulated banks toward pawn shops and non-bank consumer lenders, increasing risks for consumers already under financial strain.

The consequences of restricted credit access extend far beyond the immediate inability to make purchases. Credit cards serve as emergency funds for families without substantial savings, a category that includes a disproportionate number of African American households. For many Black families facing persistent income gaps, credit cards function not just as a convenience but as an income supplemental tool, helping to bridge the gap between earnings and the actual cost of living. When a car breaks down, a medical bill arrives, or a job loss creates temporary income disruption, credit cards can mean the difference between weathering the storm and falling into a debt spiral that damages credit for years.

The reality is that consumer credit has become essential infrastructure for African American household finance. With consumer credit growing by 10.4% in 2024, more than double the 4.0% growth in mortgage debt, Black families are increasingly dependent on expensive borrowing to maintain living standards. This isn’t a choice so much as a structural reality of trying to survive on incomes that remain roughly 60% of median white household income while facing higher costs for everything from insurance to groceries in predominantly Black neighborhoods.

Small business ownership represents another critical pathway to wealth building where African Americans face systemic barriers. Black entrepreneurs already struggle to access business loans, with approval rates significantly lower than for white business owners with similar qualifications, another systemic issue from African American banks and credit unions having limited deposits and being unable to extend loans and credit. Many small business owners use personal credit cards to fund startup costs, inventory purchases, and cash flow gaps. Restricting credit card access would eliminate this crucial financing option for aspiring Black entrepreneurs.

The rewards and benefits ecosystem could also shift dramatically. Banks have indicated they would likely reduce or eliminate rewards programs to offset lost interest income from rate caps. While this might seem minor compared to interest savings, rewards programs have become an important tool for building value, particularly for higher-credit consumers who pay balances in full monthly. The Vanderbilt Policy Accelerator research found that borrowers with credit scores of 760 or lower would see reductions in credit card rewards under a rate cap. Perhaps most concerning is the potential for credit scoring and financial history deterioration. When credit lines are closed or limits reduced, credit utilization ratios increase, which damages credit scores. This creates a downward spiral where reduced access leads to worse credit, which leads to further reduced access. For African American families working to build credit and financial stability, this could set progress back by years.

The genuine problem of high credit card interest rates and mounting consumer debt deserves serious policy attention. But effective solutions must account for how credit markets actually function and who would be most affected by reduced access. Rather than interest rate caps, policymakers should consider approaches that expand access while addressing affordability. Strengthening African American-owned banks, credit unions, and community development financial institutions would restore economic self-determination to communities that once had thriving financial ecosystems. These institutions don’t just serve African American communities they’re owned by them, led by them, and invested in their long-term prosperity. Historically, Black-owned banks have proven they can maintain sound lending practices while understanding the full context of their customers’ financial lives in ways that large, distant institutions simply cannot.

Currently, there are only 18 Black or African American owned banks with combined assets of just $6.4 billion, a tiny fraction of the industry. The absence of robust Black-owned financial institutions means that virtually all of the $740 billion in consumer credit carried by African American households flows to institutions outside the community. With African American-owned banks holding assets equivalent to less than 1% of Black household debt, the overwhelming majority of interest payments—potentially $120 billion annually—enriches predominantly white-owned institutions with no vested interest in Black wealth creation or community reinvestment. This extraction mechanism operates continuously, draining capital that could otherwise be intermediated through Black-owned institutions to support local lending and community development.

Strengthening requirements for transparent pricing, fee limitations, and responsible lending standards could protect consumers without eliminating credit availability. Regulators could mandate clearer disclosure of total costs, limit penalty fees that disproportionately burden those already struggling, and establish guardrails against predatory terms while preserving access to credit itself. Yet even these modest reforms face an uphill battle in the current political climate. The reality is that meaningful policy solutions require political will that simply doesn’t exist right now for addressing racial economic disparities directly. This makes the unintended consequences of blunt instruments like interest rate caps even more dangerous—they can restrict credit access under the banner of consumer protection while offering no viable alternatives.

The fundamental reality is clear: waiting for federal policy to solve credit access problems is a losing strategy. African American households face a specific set of economic challenges rooted in a specific history, and the solutions must be equally specific not generic approaches that treat all groups the same. The path forward requires African American communities to build their own financial infrastructure. This means capitalizing and expanding Black-owned banks and credit unions that can offer credit products designed for the actual economic realities of their customers, not risk models built on white wealth patterns. It means creating community-based lending circles and cooperative credit arrangements that leverage collective resources. It means developing alternative credit scoring systems that account for rent payments, utility bills, and other financial behaviors that traditional models ignore.

Rebuilding this sector isn’t about charity or inclusion; it’s about economic self-determination. Black-owned financial institutions have historically understood that a credit score doesn’t tell the whole story of a person’s creditworthiness, and they’ve made sound lending decisions based on relationship banking and community knowledge that large institutions can’t replicate. The challenge isn’t convincing European American owned banks to be fairer, it’s building the capacity to not need them as much. When African American communities had stronger networks of Black-owned banks, insurance companies, and credit unions, they had more options and more power. Rebuilding that infrastructure, combined with individual financial strategies that emphasize building assets and reducing dependence on consumer credit, offers a more sustainable path than hoping for beneficial federal intervention.

A 10% interest rate cap might sound appealing in the abstract, but for African American households, it likely means one thing: less access to the credit system entirely. The question then becomes not whether mainstream banks will treat Black borrowers fairly, but how communities can create their own credit access systems that serve their actual needs. That’s not a policy problem it’s a community capacity problem, and it requires community-driven solutions.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ClaudeAI.