As I grow older, I pay less attention to what men say. I just watch what they do. – Andrew Carnegie

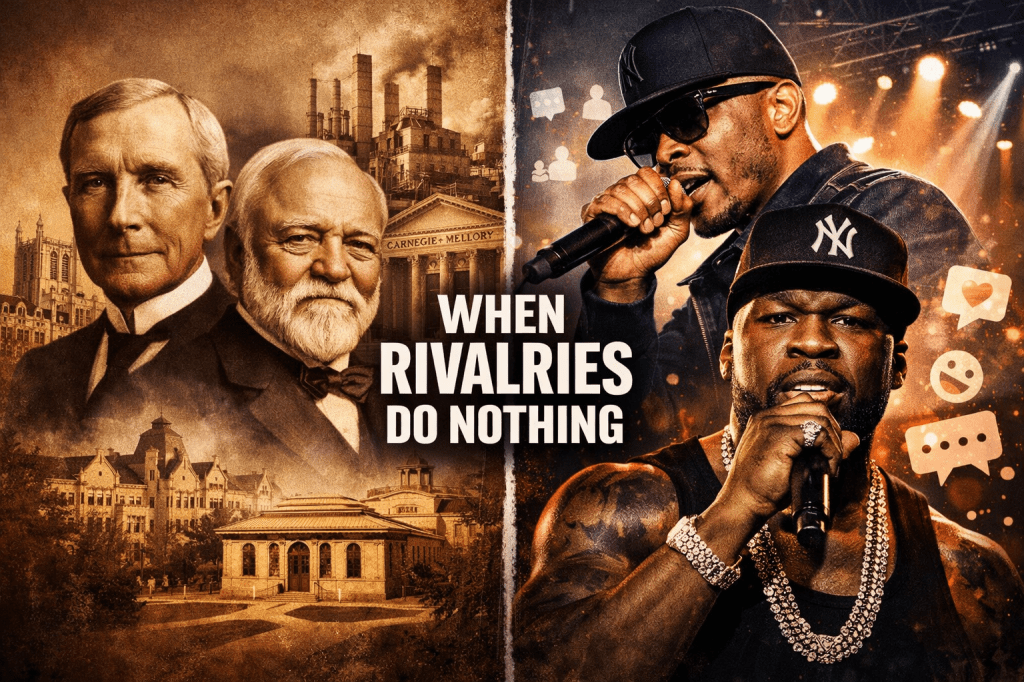

In the late 19th century, two men stood at the pinnacle of American industry and despised each other. John D. Rockefeller, the oil baron who had quietly and methodically assembled Standard Oil into a monopoly, and Andrew Carnegie, the steel magnate who built his empire on the sweat and ingenuity of immigrant labor, were the defining rivals of the Gilded Age. They competed for wealth, for prestige, for the title of richest man in America — and then, crucially, they competed for something else entirely: legacy.

What that competition produced is almost too vast to comprehend.

Andrew Carnegie funded 2,509 libraries between 1883 and 1929, with 1,681 built in the United States alone. Over 26 primary organizations — including Carnegie Mellon University, Carnegie Hall, the Carnegie Institution for Science, and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace — were established directly by him. Over 2,500 institutions and buildings worldwide bear his name. Pittsburgh, where his steel empire was born, holds the highest concentration, but the Carnegie name stretches across every state and dozens of countries. The Carnegie Corporation of New York, still active today, continues to fund education and democracy initiatives well into the 21st century.

The Rockefeller legacy is no less staggering. Dozens of major institutions bear his family’s name: Rockefeller University, The Rockefeller Foundation, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Rockefeller Center in the heart of Manhattan. His name is on halls at Cornell and Vassar, on a chapel at the University of Chicago, on an archive center that preserves the history of American philanthropy itself. And then there is the commercial legacy — when the Supreme Court broke up Standard Oil in 1911 into 34 companies, those companies eventually consolidated into what we now call ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP, Marathon Petroleum, and ConocoPhillips. That group of Standard Oil descendants today carries a combined market capitalization of approximately $1.3 trillion. The wealth Rockefeller created never stopped compounding. It simply changed form.

But here is what makes the Rockefeller legacy particularly resonant for this publication and this community: Morehouse College bears the name of Rockefeller’s former pastor, John Morehouse. Spelman College — the oldest historically Black college for women in the United States — bears the maiden name of Rockefeller’s wife, Laura Spelman. John D. Rockefeller was among Spelman’s earliest and most significant funders, contributing to the institution that would go on to educate generations of Black women who shaped American life. The man whose name is synonymous with monopoly capitalism was also, in a meaningful way, a patron of Black higher education at a moment when almost no one else was willing to be.

And the Rockefeller Foundation’s Form 990, publicly available through ProPublica’s Nonprofit Explorer, tells the ongoing story in hard numbers: total assets of $6.23 billion, net assets of $5.39 billion, and $440 million in charitable disbursements in 2023 alone — while the endowment principal remained largely intact. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, similarly available for public examination, reports total assets of $602 million and net assets of $559 million as of its most recent filing, up from $238 million in net assets just a decade ago. These institutions are still growing. They are still filing 990s. They are still deploying capital into the world more than a century after the men who created them drew their last breath.

A prior HBCU Money analysis of African American philanthropic institutions laid bare exactly why this distinction between revenue and investment income is the difference between activity and power. The King Center in Atlanta — one of the strongest African American legacy nonprofits in the country — earned $788,000 in investment income in 2022. The Ford Foundation generated $1.2 billion in investment income that same year. The Rockefeller Foundation generated $120 million. The Ford Foundation ran a $520 million deficit that year while the King Center ran a $1.28 million surplus — and Ford is the stronger institution by an almost incomprehensible margin. Ford can choose to run half a billion dollars in the red because its endowment is so vast that the deficit barely registers against the principal. The King Center’s surplus is a sign of precarity, not strength: it means the institution spent the year clinging to solvency rather than deploying capital into the world.

And then there is the Steward Family Foundation, anchored by David Steward — the wealthiest African American man in the country. In 2023 it reported $12.5 million in revenue. It held $22,000 in assets. It generated $29,000 in investment income. The wealthiest Black man in America has structured his primary philanthropic vehicle to distribute money annually and accumulate nothing — a pass-through, not a perpetual institution. His foundation will not be filing a 990 in a hundred years. It is not designed to. That is not a critique of David Steward’s generosity. It is a description of the architecture of Black philanthropy at its current upper limit: generous in the moment, invisible across generations.

That is what it looks like when a rivalry is pointed at something beyond ego.

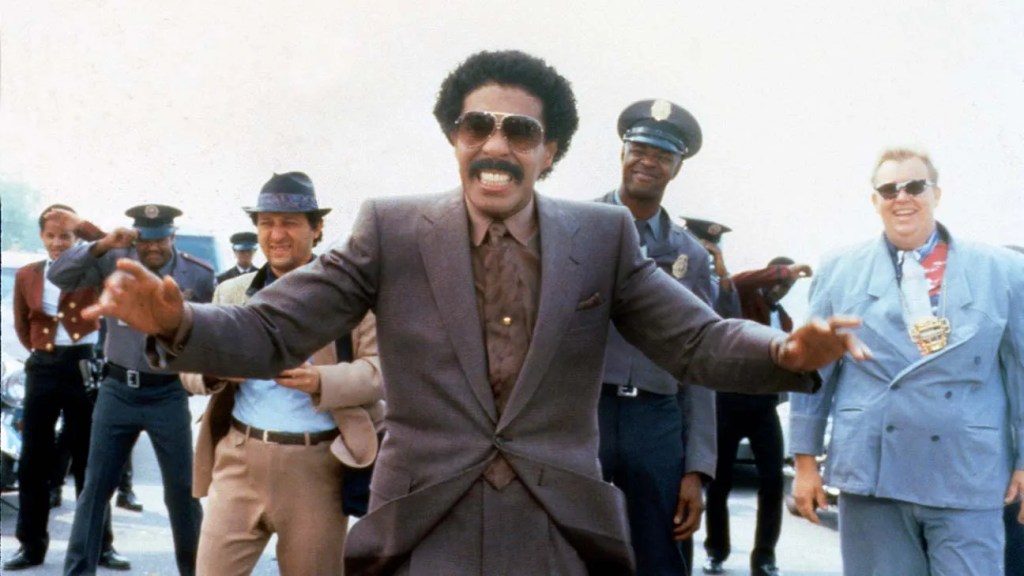

Now enter Clifford Joseph Harris Jr. and Curtis James Jackson III, better known to the world as T.I. and 50 Cent.

The beef between these two hip-hop heavyweights has been simmering for years, recently reignited and escalating into a public spectacle that has captured the attention of the culture. T.I.’s son, King Harris, has leaped into the fray on his father’s behalf. Social media has lit up. Shots have been fired — verbal ones, though given the histories of both men, the word carries particular weight. The culture watches, chooses sides, and amplifies the conflict.

And what does it produce? Absolutely nothing of value to the African American community.

That is not an overstatement. It is the most precise accounting available.

This beef will not lead to a competition over who can build the largest endowment at an HBCU. It will not culminate in 50 Cent funding a new research center at Howard University while T.I. answers by endowing a chair at Morehouse — the school that, let us not forget, already carries the indirect legacy of a man who built an oil monopoly. It will not inspire either man to deposit millions into African American-owned banks, institutions that are chronically undercapitalized and desperately in need of the kind of support that Black wealth could provide if it were directed with intention. It will not produce a dollar for African American early childhood education programs. It will not fund K-12 institutions in the underserved communities both men came from. It will not build a single research facility dedicated to attacking the health disparities — hypertension, diabetes, maternal mortality, cancer survival rates — that continue to devastate Black America at disproportionate rates.

It will do nothing. It will generate content. It will generate clout. It will generate revenue for platforms that profit from conflict. It will generate nothing else.

The Medgar and Myrlie Evers Institute — honoring the NAACP field secretary who was assassinated in his own driveway in 1963 and the woman who spent thirty years pursuing his killer to justice — reported just $107,000 in total revenue in 2023 and earned nothing in investment income. Nothing. The institution charged with preserving the legacy of one of the most consequential civil rights martyrs in American history is running on the institutional equivalent of fumes. The Martin and Coretta King Center in Atlanta, the steward of Dr. King’s legacy and one of the most visited civil rights landmarks in the country, earned $788,000 in investment income in 2022 against an endowment that remains a fraction of what the institution’s mission demands. The Malcolm X and Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Educational Center in New York — preserving the legacy of a man who came from the same streets, the same circumstances, the same defiance of a system designed to destroy him that both T.I. and 50 Cent have built careers channeling — generated $1,500 in investment income on $1.4 million in total revenue. Fifteen hundred dollars. Two men who have each earned more than that in the time it takes to read this sentence have not made these institutions whole.

This is the specific, named, documented cost of Black celebrity beef. Not an abstraction. Not a metaphor. Three institutions. Three legacies. Three sets of numbers that should make every wealthy Black American in this country uncomfortable.

This is not an indictment of either man as human beings. Both T.I. and 50 Cent have done genuine good in their communities at various points in their careers. Both are extraordinarily successful businessmen who built empires from circumstances that did not favor them. The fact that they arrived at wealth and influence from the bottom of American society makes their success stories genuinely remarkable. That is precisely why the waste of it is so tragic.

Consider the arithmetic of Carnegie’s library program alone. Two thousand five hundred libraries. Built over 46 years. In communities across the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, South Africa, and beyond. Free public libraries, at a time when access to books was a privilege of the wealthy. Carnegie gave away approximately $350 million during his lifetime — roughly $6 billion in today’s dollars — and the institutions he funded are still operating, still serving the public, still bearing his name. The competition between Carnegie and Rockefeller over who could give more, who could build more, who could leave the more lasting mark did not diminish either man’s wealth in any meaningful sense. It simply ensured that their names — and more importantly, the institutions those names represent — would outlast them by centuries.

There is a version of the T.I. and 50 Cent rivalry that could be genuinely historic. Imagine if these two men, instead of trading barbs online, announced a ten-year competition — tracked publicly, adjudicated by the community — over who could deploy their wealth most effectively for Black institutional development. Imagine 50 Cent challenging T.I. to match him dollar for dollar in deposits to Black-owned banks. Imagine T.I. responding by pledging to fund early childhood education centers in Atlanta and daring 50 to do the same in New York. Imagine the cultural energy that currently flows into this beef redirected into a genuine rivalry over who could build more, endow more, fund more, create more for a community that gave both of them everything they needed to become who they are.

The HBCU endowment gap is the starkest measure of the opportunity being squandered — and the universities that Rockefeller and Carnegie personally founded make the disparity almost impossible to look at directly.

Rockefeller founded the University of Chicago. As of June 30, 2025, its endowment stood at $10.9 billion, having returned 10.2% on investments in a single fiscal year. Carnegie founded Carnegie Mellon University. Its endowment reached $3.48 billion as of that same date, with a 10.9% net investment return for the year. Together, those two universities — founded by two men who were rivals — hold endowments exceeding $14 billion.

The combined endowments of all 100 HBCUs do not reach $6 billion. Two universities, founded by two rivals more than a century ago, hold nearly three times the endowment wealth of every HBCU in America combined.

Read that again. Two schools. Three times the endowment of one hundred.

That is not a funding gap. That is a structural chasm, built over generations, that determines whose scholars get paid, whose research gets funded, whose students graduate without debt, and whose institutions survive economic downturns without crisis. The University of Chicago and Carnegie Mellon will never face an existential budget crisis. They will never have to choose between keeping the lights on and retaining faculty. Their endowments generate enough annual return to fund operations, scholarships, and research without ever touching the principal. Meanwhile, HBCUs operate on margins that would make most community colleges uncomfortable, sustained by the dedication of their communities and the faith that the work matters — because the money has never matched the mission.

That is not a condemnation of HBCUs. It is a condemnation of the conditions under which they have been forced to operate, and an indictment of the Black wealth that has not yet organized itself to close that gap. The model for what organized private wealth can do exists and is documented in publicly filed 990s and university endowment reports. The only missing ingredient is the will to compete for something that matters.

The research funding gap is, if anything, even more consequential than the endowment gap — because research is where the future is written.

According to the National Science Foundation’s Higher Education Research and Development survey, the top 20 predominantly white institutions combined spend $36.5 billion annually on research and development. The top 20 HBCUs combined spend $712 million. That is not a gap. That is a ratio of more than 51 to 1. And to make the disparity even more concrete: 52 individual PWIs each spend more on R&D by themselves than all 20 of the top HBCU research institutions combined. Fifty-two schools. Each one, alone, outspending the entire upper tier of Black higher education research.

This is where the consequences of underfunding stop being abstract. Research funding determines who gets to ask the questions that shape medicine, technology, public policy, and economic development. It determines whose communities get studied, whose health outcomes get investigated, whose diseases get treated, whose neighborhoods get the infrastructure investments that flow from university-anchored economic development. When HBCUs are systematically excluded from this resource base, the African American community is not simply being denied prestige. It is being denied the scientific and institutional capacity to solve its own problems on its own terms.

The $35.8 billion annual research gap between the top 20 PWIs and the top 20 HBCUs is the price the African American community pays, every single year, for the failure to build research endowments at Black institutions. It is a recurring tax on Black intellectual capacity, levied not by law but by the absence of the kind of sustained private philanthropic investment that Rockefeller directed toward the University of Chicago and Carnegie directed toward Carnegie Mellon. Those institutions now have the endowments to fund research independence for generations. HBCUs are still waiting for someone to care enough to start.

The health dimension of this research gap is where the stakes become most personal. Black Americans die younger, suffer more chronically, and receive worse care at nearly every point of contact with the American medical system. Maternal mortality, hypertension, diabetes, cancer survival rates — the disparities are not mysteries. They are the predictable output of a research infrastructure that has never been adequately funded to study, understand, and treat Black patients on their own terms, in their own communities, with their own trust. The research capacity to change that exists at HBCUs and affiliated medical schools — institutions with the community relationships and patient access that predominantly white research universities have spent decades failing to build. But research capacity without research funding is just potential. Private endowments directed at HBCU medical research would save lives in ways that are measurable, documentable, and permanent. That is not a metaphor. It is a clinical fact.

African American-owned banks need the same intentional capital. Black-owned financial institutions are among the most important and most neglected infrastructure in the African American community. They survive on thin margins in the communities that need them most, while billions of dollars of Black wealth sit in institutions that have never demonstrated meaningful commitment to Black economic development. A public competition between two of the most influential men in Black popular culture over who could move more capital into Black banks would do more for Black economic infrastructure than a decade of policy advocacy.

None of this will happen because of the current beef between T.I. and 50 Cent. The cultural energy, the attention, the platform — all of it is being spent on a conflict that produces nothing, files no 990, builds no endowment, funds no scholar, saves no life.

Carnegie built 2,509 libraries. Rockefeller’s philanthropic descendants are still disbursing hundreds of millions of dollars annually, more than a century after his death, at institutions that carry his family’s name — including two HBCUs that bear the names of his pastor and his wife. The companies that descended from his oil trust are worth $1.3 trillion today. The two universities those rivals founded — the University of Chicago and Carnegie Mellon — together hold $14 billion in endowments and anchor research enterprises that collectively dwarf the entire HBCU research sector. Fifty-two individual predominantly white institutions each spend more on research annually than every top HBCU combined. The legacy of that Gilded Age rivalry is written in stone and endowment and laboratory and policy across the American landscape, in ways that will persist for another century at minimum.

What will the legacy of this beef be? Nothing. A few viral moments. A news cycle. A cultural footnote.

The competition that actually matters — the one that could put Black institutions on financial footing that no future political administration could threaten, that could fund the scholars and researchers and early childhood programs and community banks that the African American community has been building toward for generations — that competition has not yet begun.

It could begin tomorrow. The Medgar and Myrlie Evers Institute needs an endowment. The Martin and Coretta King Center needs an endowment. The Malcolm X and Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Educational Center needs an endowment. Dozens of HBCUs need endowments. Scores of African American nonprofits are running on annual donations and faith while the institutions that honor the people who bled and died for the freedom that made Black celebrity possible in the first place operate on budgets that would embarrass a mid-size law firm. A rivalry over who could change that — who could move first, who could give more, who could build something that files a 990 a hundred years from now — would be worth watching. It would be worth celebrating. It would be worth the cultural energy that is currently being fed into nothing.

It is waiting for two men, or any two men, to decide that legacy is more interesting than drama.

The 990 filings are ready to be written. The institutions are ready to be named. Morehouse and Spelman proved more than a century ago that an industrialist’s rivalry could, when channeled correctly, leave Black institutions standing long after the industrialist was gone.

The only question now is who in this generation is willing to compete for something that will still matter when they are gone.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ClaudeAI.