We will always have STEM with us. Some things will drop out of the public eye and will go away, but there will always be science, engineering, and technology. And there will always, always be mathematics. – Katherine Johnson

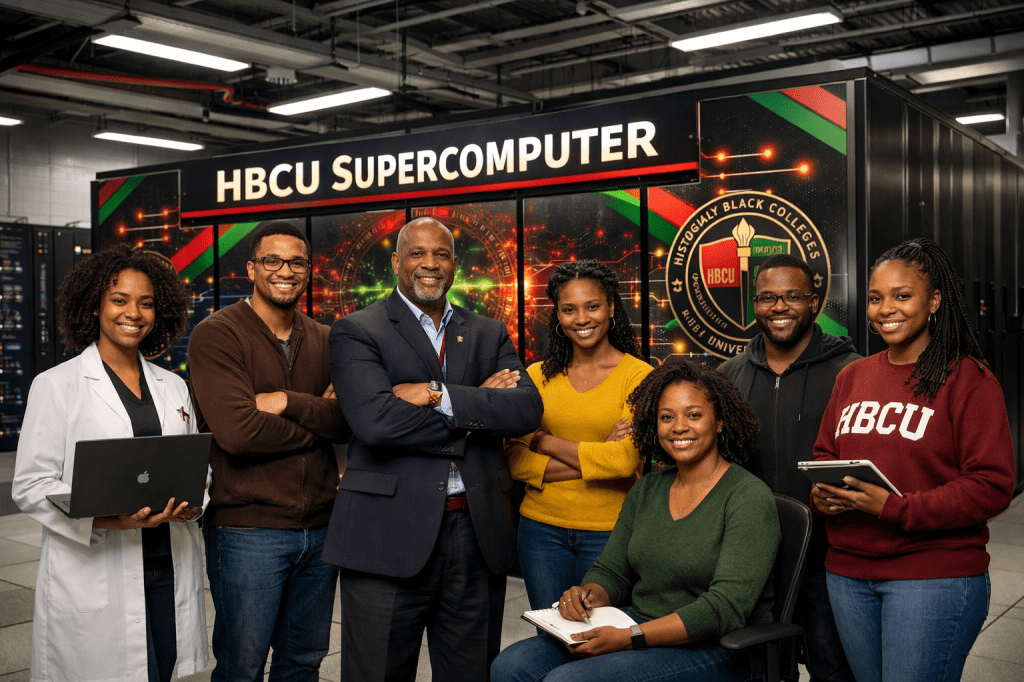

The same institutions that trained Katherine Johnson to calculate trajectories that put Americans on the moon now find themselves locked out of the computational infrastructure powering the next generation of scientific discovery. While Historically Black Colleges and Universities have long punched above their weight in producing Black STEM graduates, they remain systematically excluded from the high-performance computing resources that define cutting-edge research in the new era of AI, quantum computing, and supercomputers. It’s time for HBCUs to stop asking for access and start building their own.

The case for a Pan-HBCU supercomputer and quantum computing initiative is about survival, sovereignty, and strategic positioning in an economy where computational power increasingly determines who owns the future and who rents access to it.

Today’s research landscape is brutally simple: no supercomputer, no competitive research. Climate modeling, drug discovery, materials science, artificial intelligence, genomics, and aerospace engineering all require computational resources that most HBCUs simply cannot access at scale. While predominantly white institutions boast partnerships with national laboratories and billion-dollar computing centers, HBCU researchers often wait in lengthy queues for limited time on shared systems—if they can access them at all.

The numbers tell a stark story. According to the National Science Foundation, the top 50 research universities in computing infrastructure investment include zero HBCUs. Meanwhile, institutions like MIT, Stanford, and Carnegie Mellon operate dedicated supercomputing facilities that give their researchers 24/7 access to the tools that generate patents, publications, and licensing revenue.

This isn’t an accident. It’s the architecture of exclusion, and it’s costing African America billions in lost patents, forfeited breakthroughs, and surrendered market position. Every HBCU chemistry professor who can’t run molecular dynamics simulations is a drug that won’t be discovered. Every computer science department that can’t train large language models is an AI company that won’t be founded. Every physics researcher who can’t process particle collision data is a technology that someone else will own. This is about power—economic power, technological power, the power to shape industries rather than simply participate in them.

If the supercomputing gap is concerning, the emerging quantum divide is existential. Quantum computing represents a fundamental shift in computational paradigms with implications for cryptography, drug design, optimization problems, and artificial intelligence. Nations and corporations are investing billions to establish quantum supremacy, and the institutions that control this technology will own the intellectual property, set the standards, and capture the economic value of the next century of innovation.

HBCUs cannot afford to be spectators in this revolution. The breakthroughs that quantum-accelerated research could deliver everything from targeted therapies for diseases that disproportionately affect Black Americans to predictive models for climate impacts on Southern and coastal Black communities represent billions in economic value. More importantly, they represent the difference between being technology consumers and technology owners. Between licensing other people’s patents and collecting royalties on your own. But only if HBCUs control their own infrastructure. Or better yet, build it collectively.

Imagine a single, HBCU-owned computational facility, a crown jewel of Black academic infrastructure rivaling Los Alamos or Oak Ridge. Not distributed nodes competing for resources, but a unified campus where HBCUs collectively own land, buildings, and the machines that will mint the next generation of Black technological wealth. This is the computational arm of the HBCU Exploration Institute: a physical place where supercomputers hum, quantum processors compute, and HBCU researchers control access rather than beg for it.

The location matters. This facility needs to be somewhere politically friendly to ambitious Black institution-building, with favorable tax treatment, low energy costs, and infrastructure support. Four locations stand out:

New Mexico: Adjacent to Los Alamos and Sandia National Laboratories, with existing fiber infrastructure, favorable renewable energy costs, and a state government actively recruiting research facilities. New Mexico offers technical talent spillover, dry climate ideal for precision equipment, and proximity to Native American sovereign nations experienced in building independent institutions.

Puerto Rico: Tax incentives under Acts 20 and 22 (now Act 60) make it the Caribbean’s premier location for high-tech operations. Abundant renewable energy potential, especially solar, combined with federal research dollars without federal income tax on certain operations. Added benefit: positions HBCUs as bridge between U.S. and Caribbean research ecosystems.

Maine: Northern climate perfect for cooling systems, cheap hydroelectric power, and a state government hungry for high-tech economic development. Access to Canadian research partnerships, Atlantic subsea cable landing stations for data connectivity, and political environment favorable to institutional autonomy.

U.S. Virgin Islands: Caribbean location with full U.S. federal research funding access, generous tax incentives, and positioning as gateway to African and Caribbean collaborations. Year-round operation of field stations and research vessels, with computational infrastructure supporting the marine and atmospheric research missions.

The model is straightforward but transformative. HBCUs contribute capital to the HBCU Exploration Institute to purchase 200-500 acres outright. The land becomes HBCU property that is collectively owned, governed by an HBCU board, generating wealth for HBCU institutions in perpetuity. This isn’t leasing. This is ownership. A single state-of-the-art facility would house exascale supercomputers, quantum processors, AI training clusters, and massive data storage. Economies of scale mean more computing power per dollar than distributed nodes. Concentrated talent means better recruitment and retention. One campus means one set of operating costs, one power bill, one maintenance team.

HBCUs buy in based on their research needs and financial capacity. Larger contributors get more computational allocation and board representation, but every participating HBCU gets guaranteed access. Small institutions pool resources to punch above their weight. Research allocation follows ownership stakes, but the baseline ensures even small HBCUs can run competitive projects. Beyond serving HBCU research, the facility operates as a commercial venture. Lease computational time to corporations, government agencies, and international research collaborations. Host corporate AI training runs. Provide data center services. Every dollar generated flows back to participating HBCUs as dividends proportional to ownership stakes.

Adjacent to the computing facility, housing for rotating cohorts of HBCU researchers, graduate students, and undergraduate fellows creates a research village. Three-month to one-year residencies allow HBCU talent to work on computationally intensive projects while building networks across institutions. This becomes the intellectual hub of HBCU computational science, a place where collaborations form, startups launch, and the next generation of Black tech founders cut their teeth.

The sticker shock of supercomputing infrastructure is real but so is the cost of exclusion. A competitive supercomputing facility costs between $100-200 million to build and $10-30 million annually to operate, depending on scale and capability. Quantum computing infrastructure is still evolving, but meaningful access could require $50-75 million in initial investment. These aren’t small numbers, but they’re achievable through a combination of federal investment, private philanthropy, and strategic partnerships.

The first call should be to African American and Diaspora wealth both domestic and international. High-net-worth Black individuals, African tech billionaires, Caribbean family offices, and Diaspora investment networks represent untapped capital that understands the long-term value of Black institutional ownership. These are investors and philanthropists who won’t demand the same strings or ideological alignment tests that mainstream foundations impose. Traditional foundations like Mellon and Gates may follow once momentum builds, but Diaspora capital should lead. This ensures the vision remains accountable to Black communities rather than foundation program officers.

The priority for corporate partnerships should be African American and Diaspora-owned tech companies and investors who understand the strategic value of Black computational sovereignty. Seek partnerships with Black-led private equity firms, African tech entrepreneurs, and Caribbean technology investors before approaching mainstream tech giants. When engaging with companies like Microsoft, Google, IBM, and NVIDIA, structure deals that provide HBCUs with hardware, software, and expertise in exchange for joint research projects and equity participation but ensure HBCUs retain majority control and IP ownership. The goal is capital and resources, not dependence.

Federal funding streams exist like the CHIPS and Science Act, NSF Major Research Instrumentation grants, Department of Energy computing initiatives, and NASA research infrastructure programs though the current political environment makes federal support uncertain at best. HBCUs should build relationships and develop proposals now, but plan for a future administration more committed to research equity. In the meantime, the strategy must center on private capital and revenue generation that doesn’t depend on federal goodwill. Once operational, the facility could generate substantial revenue through commercial computing services, corporate research partnerships, and federal agency contracts. The University of Texas at Austin’s Texas Advanced Computing Center generates tens of millions annually through exactly this model, money that flows back into research capacity and student support. An HBCU-owned facility would channel those revenues directly to participating institutions as dividends proportional to ownership stakes.

The real value of HBCU-owned computational infrastructure goes far beyond the machines themselves. It’s about training the next generation of computational scientists, quantum engineers, and AI researchers who don’t just work for tech companies but found them, own them, and profit from them. Students at HBCUs with robust computing facilities wouldn’t just learn about supercomputers in textbooks they’d gain hands-on experience optimizing code for parallel processing, debugging quantum algorithms, and managing large-scale computational workflows. These aren’t abstract skills; they’re the exact expertise that tech companies and national laboratories desperately need and are willing to pay premium salaries to acquire. More importantly, they’re the skills that enable students to launch their own computational startups rather than simply joining someone else’s.

Faculty recruitment and retention would transform overnight. Try recruiting a top-tier computational chemist or AI researcher to an institution where they’ll spend half their time begging for computing time elsewhere. Now imagine recruiting that same researcher with the promise of dedicated access to world-class computing infrastructure and a path to commercialize their discoveries. The competitive landscape shifts dramatically.

This proposal aligns seamlessly with emerging initiatives like the HBCU Exploration Institute and the Coleman-McNair HBCU Air & Space Program outlined in recent strategic planning documents. These ambitious programs envision HBCUs leading research expeditions, operating research vessels and aircraft, and conducting aerospace missions. None of this is possible without serious computational infrastructure. Climate modeling for polar expeditions, satellite data processing, aerospace engineering simulations, deep-sea mapping analysis—these all require supercomputing resources. Want to analyze genomic data from newly discovered marine species? Process atmospheric measurements from research aircraft? Model propulsion systems for small satellites? You need computational power, and lots of it.

A Pan-HBCU Computing Consortium wouldn’t just support these exploration initiatives it would accelerate them, turning HBCUs into genuine leaders in exploratory science rather than junior partners dependent on others’ computational generosity. And every discovery, every patent, every breakthrough would belong to HBCU institutions and their researchers.

The window for building this capacity is closing. As quantum computing matures and AI systems become more computationally intensive, the institutions with infrastructure will accelerate away from those without. The gap between computational haves and have-nots will become unbridgeable, and HBCUs will be permanently relegated to second-tier research status which means second-tier revenue, second-tier patents, and second-tier wealth creation.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. The HBCU community has something that other institutions don’t: a shared mission, deep trust networks, and a history of collective action in the face of systemic exclusion. These institutions didn’t wait for permission to educate Black students when others wouldn’t. They didn’t wait for invitations to produce world-class scientists and engineers. They built their own institutions and proved the doubters wrong.

The same spirit that created HBCUs in the first place, the audacious belief that Black excellence could not be contained or denied must now be channeled into building the computational infrastructure these institutions need to compete and win in the 21st century. The question isn’t whether HBCUs can afford to build their own supercomputer and quantum computing infrastructure. The question is whether they can afford not to. In a world where computational power increasingly determines who shapes the future and who profits from it, HBCUs must choose between dependence and ownership.

The choice should be obvious. It’s time to build.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ClaudeAI.