The most difficult thing in life is to know yourself. — Thales

By any reasonable historical standard, Warren Buffett’s rejection by Benjamin Graham is more than a quaint anecdote; it is a powerful parable about institutional loyalty and long-term economic strategy. Graham, the father of value investing, turned away the future Oracle of Omaha not because Buffett was unqualified—far from it—but because he had a principle. Graham hired exclusively European American Jews at a time when Wall Street’s doors were locked tight against them. It was his quiet resistance to systemic exclusion and a way to build a parallel institution that could compete and thrive. Graham wasn’t interested in assimilation; he was focused on insulation, independence, and empowerment. The same cannot be said about the leadership structure of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), particularly their business schools.

A decade has passed since a comprehensive review was last undertaken on the leadership of HBCU business schools. One would hope that the intervening years would have ushered in a renaissance of internal cultivation—an era where HBCU alumni, steeped in the culture, history, and mission of these institutions, took the reins of their business schools. That hope remains, for the most part, unrealized. Instead, many HBCU B-schools continue to be led by individuals who are not products of these institutions, and in many cases, are fundamentally disconnected from the unique economic and cultural needs of the African American community.

The appointment of deans and senior faculty from predominantly white institutions (PWIs) is often lauded as a move toward “excellence” or “best practices.” The coded language of meritocracy is a familiar refrain—best person for the job, regardless of background. But this belief, as commonly practiced within HBCUs, is a convenient myth. It sidesteps the structural disadvantages HBCU graduates face in academia and business, and reinforces a dependency on external validation and leadership.

The consequence? A business education ecosystem within HBCUs that remains divorced from the very communities these schools are intended to serve. There is no pipeline, no incubator of internal talent, no clear strategy to empower HBCU alumni to lead, govern, and shape the next generation of Black business leadership.

Institutional Amnesia

In failing to privilege their own alumni in leadership selection, HBCU B-schools suffer from what might be called institutional amnesia. There is little effort to study and replicate the success of institutions that have prioritized internal development. Jewish, Catholic, and even Mormon institutions have all built robust networks by leveraging internal cultural capital and aligning institutional leadership with community objectives. HBCUs, by contrast, often appear to suffer from an inferiority complex that manifests in a relentless pursuit of PWI credentials as a proxy for excellence.

Even when HBCU alumni are in the pipeline, they are frequently passed over in favor of candidates whose resumes boast affiliations with Ivy League or flagship public institutions. The irony is rich and troubling: HBCUs, which claim to be dedicated to the uplift of African Americans, routinely reject their own in favor of the very systems that have historically excluded them.

The Data Tells the Story

Of the 85 accredited HBCU business schools and departments (based on the latest available data), fewer than 20% are led by HBCU alumni. Of that number, fewer than half have received their undergraduate and graduate education at an HBCU, further diluting the institutional knowledge that could be reinvested back into the system.

By contrast, 75% of business school deans and department chairs at Ivy League universities hold at least one degree from an Ivy League institution. This underscores the importance these institutions place on continuity, network loyalty, and internal cultural capital.

Lack of a Succession Strategy

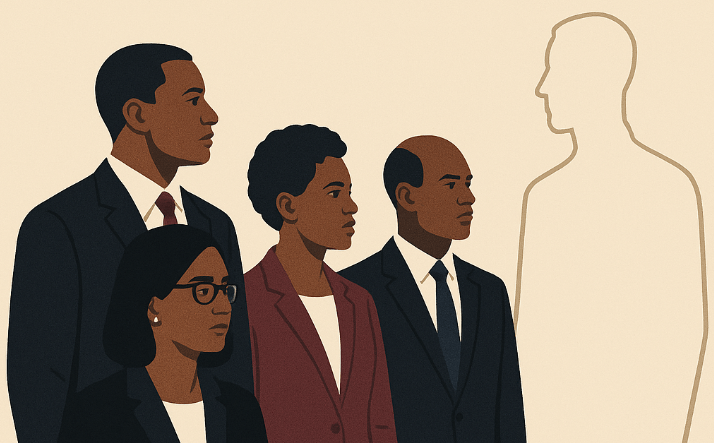

The dearth of HBCU alumni in leadership roles is not merely a matter of optics—it is a strategic failure. The absence of a deliberate succession plan, where institutions identify, mentor, and elevate their own talent, weakens the intellectual and operational spine of HBCU B-schools. When young Black scholars and students do not see themselves reflected in positions of power within their own institutions, the implicit message is that their ascent must take place elsewhere.

Anecdotes abound of promising scholars who, having been educated and initially employed at HBCUs, eventually decamp to PWIs for better pay, prestige, or professional development. When those same scholars become leaders elsewhere, their institutional loyalty rarely circles back. The brain drain becomes self-perpetuating.

Cultural Incongruence and Strategic Drift

Leadership from outside HBCUs is not inherently problematic. However, leadership that does not understand or prioritize the mission-specific challenges and opportunities of HBCUs can lead to strategic drift. The market-driven nature of business education already pushes HBCUs to chase prestige metrics that are often defined by PWI standards—AACSB accreditation, international rankings, publication quotas. Yet these metrics seldom align with the needs of the African American community.

Who is building a curriculum around cooperative economics? Who is training students to start, fund, and grow businesses in historically Black neighborhoods? Who is leading research on Black entrepreneurship, Black banking, and financial exclusion? These priorities require not just academic competence but cultural commitment—something often missing in leadership that has not been formed within HBCUs.

The Cost of Outsourcing Leadership

The preference for external hires is also an expensive habit. Recruitment searches for deans can cost upwards of $250,000 when executive search firms are engaged. The revolving door of short-term leadership appointments, another consequence of weak institutional loyalty, creates instability in fundraising, student recruitment, and faculty morale.

Moreover, the indirect costs are enormous. When leadership lacks vision rooted in the mission of HBCUs, partnerships are misaligned, fundraising strategies are tone-deaf, and entrepreneurial ecosystems are underdeveloped. Business schools are economic engines, and the failure to connect them authentically to the community they serve is a missed opportunity of staggering proportions.

What Would Graham Do?

The story of Benjamin Graham and Warren Buffett is not merely about individual relationships; it is a case study in institutional integrity. Graham’s commitment to his community was not performative. It was strategic, values-driven, and unapologetically intentional. He understood that talent alone was insufficient. It had to be nurtured, protected, and positioned within the community’s own institutions.

African American leaders in education, particularly those responsible for HBCUs, must ask themselves: what kind of ecosystem are we building? Do we merely seek validation from the same institutions that denied us access for generations? Or are we committed to the difficult, often thankless work of institution-building?

The answer may well determine the fate of HBCUs in the 21st century.

A Call to Action

First, HBCU business schools must create formal succession pipelines for leadership from within their own alumni networks. This includes mentoring programs, leadership fellowships, and internal promotion tracks that incentivize long-term engagement.

Second, boards of trustees and presidential leadership must reexamine hiring criteria. Cultural alignment and mission understanding must be weighted as heavily as academic credentials.

Third, HBCUs should begin benchmarking themselves not against Harvard or Wharton but against institutions that have successfully used internal leadership to drive community outcomes. The benchmarks for success must be redefined to reflect mission, not mimicry.

Finally, alumni must hold their institutions accountable. Donations should come with expectations for institutional integrity. If alumni are good enough to fund these schools, they are certainly good enough to lead them.

HBCU B-schools sit at the intersection of education, economics, and cultural preservation. Their leadership must reflect that complexity. The time for apologetic hiring practices and external validation is over. It is time for HBCUs to know themselves—and to trust themselves enough to lead from within.