“I know I got it made while the masses of black people are catchin’ hell, but as long as they ain’t free, I ain’t free.” – Muhammad Ali

The recent news that Intel will discontinue its $1 million annual funding of North Carolina Central University’s (NCCU) Technology Law and Policy Center is more than just a line item in the university’s budget. It is a sharp reminder of how precarious institutional development becomes when African American colleges and universities rely on the European American corporate cycle of generosity and withdrawal. Where is African American corporate philanthropy is a pertinent question, but an article for another day.

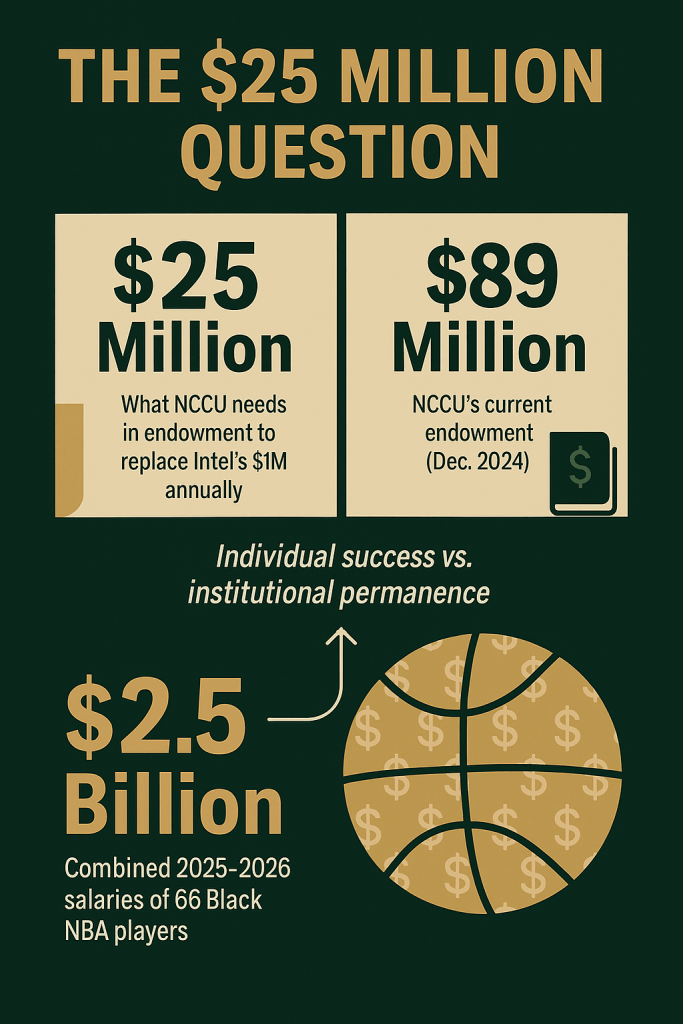

Intel’s departure leaves a gap that must now be filled through other means. But the mathematics of filling it points to a broader truth: without substantial, permanent endowments, HBCUs will remain vulnerable to the political and financial whims of European American corporations. To replace $1 million in annual program funding, NCCU would need to raise between $20 million and $25 million in endowment principal assuming a 4–5% annual spending rate, the standard in higher education finance.

The fact that an entire academic pipeline, designed to produce future African American lawyers and policymakers, can be destabilized by a single corporate decision underscores the fragility of HBCU institutional power. And it raises a haunting contrast: while 66 African American NBA players will together earn $2.5 billion in salaries this upcoming season, not a single African American university controls an endowment robust enough to insulate it from the kind of disruption Intel’s withdrawal has now caused.

The mechanics are straightforward. Endowments work by pooling donated capital, investing it, and spending a sustainable portion of annual returns—usually 4–5%. To replace Intel’s $1 million annual gift, NCCU must therefore build an endowment of $20–25 million. This is not extraordinary by university standards. At most predominantly white institutions (PWIs), a $25 million endowment is considered modest. At Harvard, Yale, or Stanford, it would not even make the footnotes. Yet for NCCU, an institution with an endowment of $89 million as of December 2024, the sudden need for another $20–25 million underscores the gap between HBCUs and their white peers.

The underlying truth is that corporate funding is inherently unstable. It ebbs and flows with market cycles, political administrations, and corporate priorities. Endowments, however, endure across generations. The very act of raising such capital is itself an exercise in institutional power: it demonstrates to the world that the university and its community can stand on their own financial feet.

Intel did not single out NCCU maliciously. The company is undergoing a profound transformation, not least because the U.S. government has become its largest shareholder after a multi-billion-dollar deal with the Trump administration. Like other firms facing political scrutiny, Intel is quietly shedding high-profile DEI commitments. For NCCU, however, the effect is real. The Technology Law and Policy Center was designed to provide African American law students with training in emerging technology and policy—a space historically closed to Black lawyers. It also featured internships at Intel, summer placements, and the now-defunct “Intel Rule,” which required outside law firms to staff diverse teams if they wanted Intel’s business. Now, without a replacement funding mechanism, the Center risks contraction. Students will still enroll. Faculty will still teach. But the acceleration that Intel’s money provided—the ability to recruit nationally, to build cutting-edge programming, to give students exposure to high-tech legal practice—will slow.

Enter the paradox of the NBA’s 66 Black players earning $25 million or more in the upcoming season. Collectively, those 66 players will earn $2.5 billion in salary during the 2025–2026 season. Each of these players individually makes at least what NCCU would need to permanently replace Intel’s $1 million annual commitment through endowment. The collective sum is staggering: $2.5 billion in one season—enough to seed $25 million endowments at 100 HBCUs.

It is not about individual responsibility. No one player can be expected to save an institution. But collectively, the paradox points to the imbalance between African American individual wealth and African American institutional poverty. Even if just 10% of that wealth—$250 million—were organized and directed into HBCU endowments, the result could replace Intel’s contribution not only at NCCU but across multiple campuses. Yet there is no mechanism, no institutional strategy, no coordinated pipeline that directs such flows into African American universities. This is not new. For decades, African American excellence has been harvested at the level of the individual, while African American institutions have remained underfunded. The NBA is simply the latest, most visible example.

The Intel withdrawal reminds us of a hard truth: reliance on outside benevolence is not a strategy for power. It is, at best, a strategy for survival. Corporate giving is always the first budget item to shrink when recession looms or political winds shift. For HBCUs, this means programs rise and fall on decisions made in Silicon Valley or Wall Street boardrooms—far removed from Durham, Tallahassee, Baton Rouge, or Montgomery. The vulnerability is compounded when African American communities assume that the generosity of corporations will substitute for building our own endowments. The danger is not simply financial but cultural: it conditions us to believe that power comes from outside, not from within.

Intel’s $1 million a year was not charity—it was investment. It bought Intel goodwill, a trained pipeline of diverse lawyers, and reputational capital in the DEI era. Now that DEI is politically unpopular, the investment is deemed expendable. This is why endowments matter. They are not subject to the quarterly report or the election cycle. They anchor institutions in the long term.

Let’s be clear about the scale of the challenge. The combined endowments of all HBCUs hover around $4 billion, compared to more than $800 billion at PWIs. Harvard alone has an endowment of nearly $52 billion. NCCU’s endowment stands at $89 million. To raise an additional $20–25 million to replace Intel’s support would represent a 22–28% increase in its current endowment base. Such a leap is achievable—but it requires strategy. It means cultivating alumni giving systematically. It means leveraging African American wealth beyond alumni, drawing in professional athletes, entertainers, and entrepreneurs. It means creating vehicles—donor-advised funds, pooled endowments, institutional investment cooperatives—that make giving both efficient and impactful. Most of all, it means shifting mindset. We must stop thinking of endowments as luxuries reserved for Ivy League institutions. They are necessities. They are the only way to secure institutional independence.

The Intel decision can serve as a turning point, if we are willing to see it clearly. Corporations are not institutional guardians. They may play a role, but they will not underwrite our survival. Their goals are their own. When interests diverge, as they now have, funding vanishes. Individual wealth must be institutionalized. The contrast between NBA salaries and HBCU endowment poverty is not about shaming athletes. It is about building structures that make institutional giving the default, not the exception. Endowments are the only safety net. No government program, no corporate sponsorship, no philanthropic fad can substitute. Only endowments give institutions perpetual capacity to fund themselves.

What would it take, concretely, for NCCU to raise the $25 million needed? A handful of major gifts in the $2–5 million range from alumni, athletes, or African American business leaders could jump-start the campaign. NBA, NFL, and WNBA players could be recruited to create a pooled fund. Instead of individual gifts, imagine a collective “Athletes for HBCU Endowments” initiative. African American foundations and community funds could direct grants toward seed capital, matched by alumni. If every NCCU law graduate gave $1,000 a year for ten years, the cumulative effect would approach the tens of millions. NCCU could also partner with African American-owned banks and investment firms to maximize returns and circulate dollars within the community. The strategy would not only replace Intel but set a precedent: when outside money leaves, we do not shrink. We build.

The broader question is not whether NCCU will survive the loss of Intel’s support. It will. The real question is whether African American institutions will continue to live in the shadow of dependency—or whether we will use moments like this to chart a new course. The paradox of $2.5 billion in NBA salaries versus the need for a $25 million endowment is not just a rhetorical flourish. It is a mirror held up to African America. It asks whether we will continue to celebrate individual wealth while neglecting collective survival.

Every dollar of Intel’s withdrawal can be replaced. But only if African American wealth is organized. Only if alumni, athletes, and entrepreneurs see endowments not as gifts but as obligations. Only if we remember that the true measure of power is not what any one of us earns, but what we can build together.

Intel has reminded us of an uncomfortable truth: corporate giving is temporary. Endowments are permanent. To replace $1 million a year, NCCU needs $25 million in endowment. That number is not insurmountable. It is the equivalent of one NBA salary in a single season. There are 66 African American players earning at least that much this year alone, with combined salaries of $2.5 billion. The juxtaposition is stark: individuals flourish while institutions starve. The future of HBCUs—and the broader African American ecosystem—depends on closing that gap. Until African America learns to institutionalize its wealth, every Intel withdrawal will feel like a crisis. But the day we build our endowments, such exits will be footnotes. And our institutions will finally stand on the firm ground they have always deserved.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.

Charlamagne Tha God & Jemele Hill: The Debate They Both Got Right and Wrong

“If you don’t own anything, you don’t have any power.” — Dr. Claud Anderson

When Charlamagne Tha God proclaimed, “Wake your ass up and get to trade school!” after NVIDIA’s CEO Jensen Huang suggested that the next wave of American millionaires will come from plumbers and electricians, he was not simply shouting into the void. He was echoing a national frustration, one rooted in the rising irrelevance of a degree-driven economy that no longer guarantees stability or wealth. Student debt has grown into a generational shackle, corporate loyalty is dead, and a working class once promised a middle-class life for earning a degree has found itself boxed out of the very prosperity it was told to chase. Charlamagne’s message resonated because trades feel like a lifeboat in an economy where white-collar work has become overcrowded, uncertain, and increasingly automated. But Jemele Hill’s response, “There’s nothing wrong with getting a trade, but the people in the billionaire and millionaire class aren’t sending their kids to trade schools” was the kind of truth that punctures illusions. She was not critiquing the trades; she was critiquing the belief that skill, in isolation from ownership, can produce power.

Her point hits harder within African America because our community has historically been guided into labor paths whether trade or degree that position us as workers within someone else’s institutions. It is not a coincidence. As HBCU Money examined in “Washington Was The Horse And DuBois Was The Cart”, the historical tension between industrial education and classical higher learning was never about choosing one or the other. It was about sequencing. Booker T. Washington understood that African America first needed an economic base, a foundation of labor mastery and enterprise capacity. W.E.B. DuBois emphasized intellectual development and leadership cultivation. But Washington was right about one thing: without an economic foundation, intellectual prowess has no institutional home. And without institutional homes, neither the trade nor the degree can produce freedom. African America today is suffering because we abandoned Washington’s base-building and misinterpreted DuBois’s talent development as permission to serve institutions built by others.

Charlamagne’s trade-school enthusiasm fits neatly into Washington’s horse, the practical skill that generates economic usefulness. But Hill’s critique reflects DuBois’s cart understanding how society actually distributes power. The mistake is that neither Washington nor DuBois ever argued that skill alone, or schooling alone, was enough. Both ultimately pointed toward institutional ownership. Neither wanted African Americans to remain permanently in the labor class. The trades were supposed to evolve into construction companies, electrical firms, cooperatives, and land-based enterprises. The degrees were supposed to evolve into banks, research centers, hospitals, and political institutions. What we actually did was pursue skills and credentials not power. We mistook competence for control.

This is why the trades-versus-degrees debate is meaningless without ownership. Becoming a plumber or an electrician provides income, but not institutional leverage. Becoming a lawyer or an accountant provides upward mobility, but not institutional control. A community with thousands of tradespeople and thousands of degreed professionals but without banks, construction firms, land ownership, hospitals, newspapers, media companies, sovereign endowments, or venture capital funds is still a community of laborers no matter how educated or skilled.

This structural truth becomes even clearer when viewed through the lens of how the wealthiest Americans use education. HBCU Money’s analysis, “Does Graduate School Matter? America’s 100 Wealthiest: 44 Percent Have Graduate Degrees”, observes that while nearly half of America’s wealthiest individuals do hold graduate degrees, the degrees themselves are not the source of wealth. They are tools of amplification. They work because the individuals earning them already have ownership pathways through family offices, endowments, corporations, foundations, and networks that translate education into power. Graduate school matters when you have an institution to run. It matters far less when your degree leads you into institutions owned by others.

African American graduates rarely inherit institutions; they inherit responsibility to institutions that do not belong to them. So the degree becomes a ladder into someone else’s building. And trades, stripped of the communal ownership networks they once fed, become a ladder into someone else’s factory, subcontracting chain, or municipal maintenance operation. We are always climbing into structures that someone else owns.

This cycle was not always our trajectory. The tragedy is that HBCUs once created institutional ecosystems where skill and knowledge were used to build African American economic capacity—not merely transfer it outward. As HBCU Money argued in “HBCU Construction: Revisiting Work-Study Trade Training”, many HBCUs historically operated construction, carpentry, and trade programs that literally built the campuses themselves. Students learned trades while constructing residence halls, dining facilities, barns, academic buildings, and infrastructure that the institution would own for generations. That model kept money circulating internally, built hard assets, created institutional wealth, and established capacity for African American contracting firms. It produced not just skilled laborers it produced apprentices, foremen, entrepreneurs, and business owners. It produced Washington’s economic foundation.

The abandonment of these models created a void. Trades became disconnected from institutional development. Degrees became pathways to external employment. And HBCUs which once trained students to build institutions were transformed into pipelines feeding corporate America and federal agencies that rarely reinvest into African American institutions at scale. This is why the trade-school-versus-college debate is hollow. Both are simply skill paths. Without ownership, both lead to dependence.

Charlamagne’s sense of urgency comes from watching African American millennials and Gen Z face an economy with fewer footholds than their parents had. But urgency alone cannot produce strategy. Hill, consciously or unconsciously, pointed out that the wealthy understand something we have not fully grasped: the ultimate purpose of skill, whether manual or intellectual, is to strengthen one’s own institutional ecosystem not someone else’s. The wealthy do not send their children to college to find jobs; they send them to college to learn to oversee family enterprises, influence policy, govern philanthropic endowments, and maintain social capital networks. A wealthy family’s electrician child does not go into electrical maintenance he goes into managing the electrical firm the family owns.

This is the distinction African America must confront. We keep choosing roles instead of building infrastructure. We choose jobs. We do not choose institutions. We chase wages. We do not chase ownership. This is not because African Americans lack talent or ambition. It is because integration disconnected African America from its economic development logic. In the push to integrate into white institutions, we abandoned the very institutions that anchored our communities—banks, hospitals, insurance companies, manufacturing cooperatives, and HBCU-based work-study and trade ecosystems.

The future requires rebuilding a Washington-first, DuBois-second model. The horse that is the economic base must return. The cart that is the intellectual class must attach to institutions that the community owns. Trades should feed African American contracting firms, electrical cooperatives, and infrastructure companies that service Black communities and employ Black workers. Degrees should feed African American financial institutions, research centers, HBCU endowments, political think tanks, and venture funds. Every skill, trade, or degree must be tied to institutional expansion.

Otherwise, we will continue mistaking income for empowerment, education for sovereignty, and representation for ownership. Trade or degree, individual success means little when the community remains institutionally dependent. Wealth that dies with individuals is not power; it is a temporary advantage. Power is continuity. Power is structure. Power is ownership.

The choice before African America is not between trade and degree. It is between labor and ownership. No skill, not plumbing, not engineering, not medicine, not law creates power without institutions. We are not lacking talented individuals; we are lacking the institutional architecture that turns talent into sovereignty.

Charlamagne spoke to survival. Hill spoke to structure. Washington spoke to foundation. DuBois spoke to leadership. The synthesis of all four is the path forward. Without institutions, African America will always remain the labor in someone else’s empire even when the labor is highly paid, well-trained, and excellently credentialed. Only ownership transforms skill into power, and without rebuilding our institutional ecosystem, we will continue to debate trades and degrees while owning neither the companies nor the universities.

Ownership is the only path. Without it, neither the horse nor the cart will ever move.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.

1 Comment

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged African American cooperative economics, African American economic independence, African American entrepreneurship, African American institutional ownership, Black community ownership, Black construction industry, Black institutional power, black wealth building, Black-Owned Businesses, Booker T. Washington economic philosophy, charlamagne tha god, Charlamagne Tha God commentary, economic empowerment African America, HBCU economic strategy, HBCU Endowment Growth, HBCU trade training, institutional sovereignty Black community, jemele hill, Jemele Hill analysis, trades vs degrees debate, W.E.B. DuBois leadership development, wealth gap analysis