“The regeneration of Africa means that a new and unique civilization is soon to be added to the world.” — Dr. Edward Wilmot Blyden

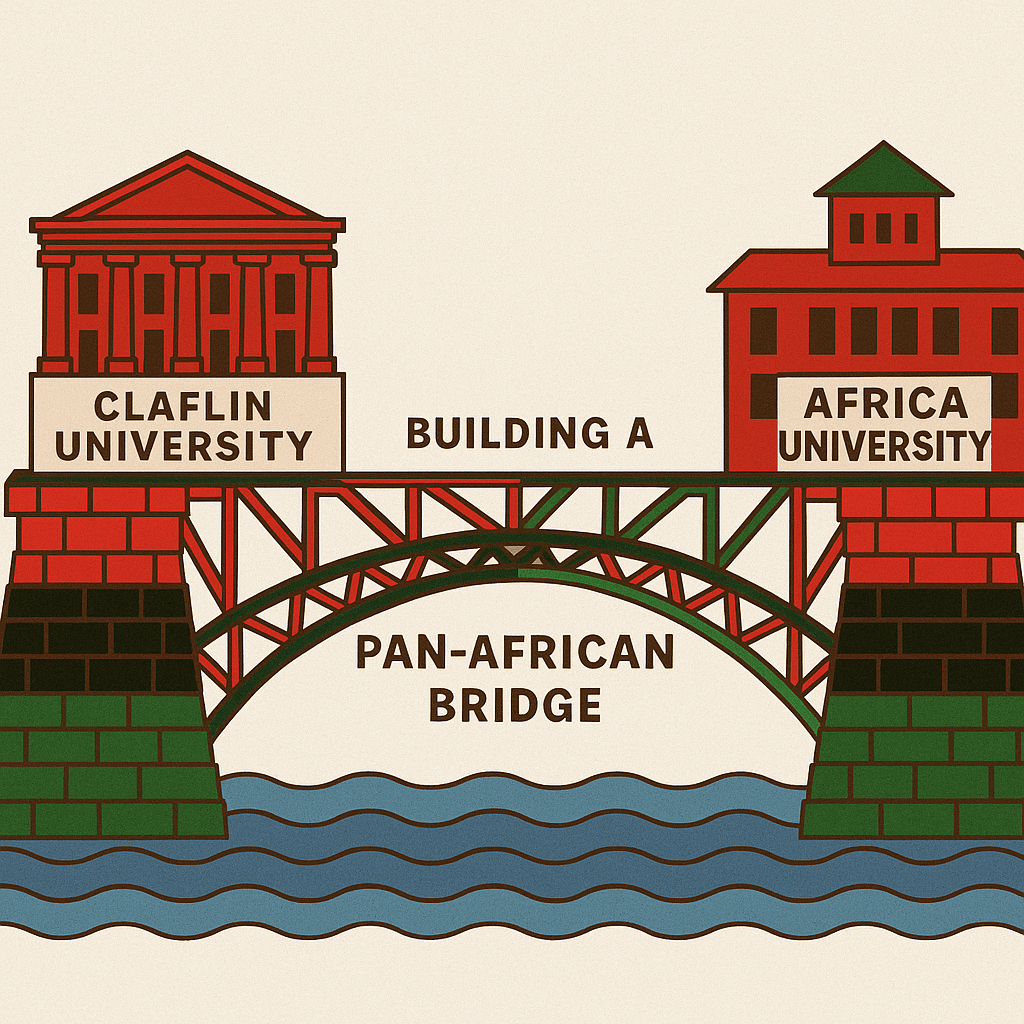

In a world increasingly threatened by climate change, biodiversity loss, and global inequality, it is not only science that must rise to meet the moment—it is institutions. The historic collaboration between Claflin University, a leading Historically Black College and University (HBCU) in Orangeburg, South Carolina, and Africa University in Zimbabwe is a testament to what the future of Pan-African higher education cooperation can and must look like.

As seen in the powerful image of four smiling graduates—young scholars representing Africa University’s Class of 2025—this partnership is more than symbolic. These four AU alums were awarded Master of Science degrees in Biotechnology and Climate Change through an online program with Claflin University. It marks a significant step forward in bridging the gap between HBCUs and African universities, offering not just degrees, but transformation, elevation, and a realignment of institutional relationships across the African Diaspora.

Claflin University’s Dr. Gloria McCutcheon, a seasoned environmental scientist and scholar, alongside Africa University’s Dr. James Salley, deserves our deepest thanks and congratulations for stewarding this visionary effort. This is more than an academic exercise. It is an investment in Black global agency—an institutional architecture that boldly resists the neo-colonial fragmentation of Black intellect and instead forges knowledge capital across oceans.

The Institutional Revolution: Why It Matters

Historically, relationships between HBCUs and African universities have been underdeveloped. While shared historical and cultural lineages run deep, formal cooperation in research, degree programs, and faculty development has often been episodic and underfunded. This is due in part to a lack of intercontinental policy alignment, but also due to the structural underinvestment in both HBCUs and African institutions of higher learning.

Yet this partnership challenges that stagnation. By aligning their academic missions, Africa University and Claflin University are modeling a future where Black institutions on both sides of the Atlantic are no longer rivals for Western validation, but co-creators of global excellence.

Biotechnology and climate change are not only timely fields—they are strategic. These disciplines shape the future of agriculture, health, water, and energy. As climate change disproportionately affects the Global South, it is imperative that scientists and researchers from Africa and the African Diaspora lead in developing regionally grounded and globally relevant solutions. The MS program is designed with this in mind, empowering graduates with the tools to confront challenges that affect their communities directly.

This is the praxis of Black institutional sovereignty. It is not merely symbolic, it is materially transformational.

Online Education as Pan-African Infrastructure

One of the most remarkable elements of this partnership is its fully online format. In doing so, it sidesteps the exorbitant costs and restrictive visa policies that often inhibit African students from accessing U.S.-based graduate education. Rather than uprooting scholars from their communities and obligations, this model allows them to remain embedded in the ecosystems they intend to serve.

It is also a vital counterpoint to the often exploitative model of international student tuition dependency seen at many Predominantly White Institutions (PWIs). Instead of recruiting African students primarily as revenue sources, this partnership honors them as scholars and change-makers—collaborators in knowledge production, not customers.

This is especially crucial as online education technologies mature and expand access. The future of African Diaspora cooperation must be hybrid and tech-savvy, using every digital tool available to scale education, connect institutions, and reinforce the sovereignty of Black intellectual spaces.

Claflin’s leadership in this area signals what is possible for other HBCUs. Morehouse School of Medicine has already begun integrating global health partnerships, and Howard University has longstanding African studies initiatives. Yet this direct academic program collaboration between Claflin and Africa University sets a new precedent—one that should become a norm, not an exception.

The Bigger Picture: Climate, Biotechnology, and Black Sovereignty

The selection of Biotechnology and Climate Change as the focus of this master’s program is a strategic masterstroke. Climate adaptation, agricultural sustainability, and bio-innovation are the battlegrounds of the 21st century. From Nairobi to New Orleans, African-descended people are often the first to feel the tremors of ecological collapse. We are also, too often, the last to benefit from the technological revolutions responding to it.

By placing young African scholars at the cutting edge of these fields, Claflin and Africa University are not just preparing students for careers—they are preparing them to lead revolutions. Innovations in biotech can reshape everything from vaccine distribution to drought-resistant crops. Expertise in climate change can determine which communities survive sea-level rise, which economies can adapt to volatile weather, and which governments can formulate climate justice policies that center the most vulnerable.

This partnership builds knowledge that is simultaneously scientific and sovereign. It reflects a belief that Black students should not just study solutions crafted elsewhere, but invent their own. In a world that too often imposes external “development” frameworks on African nations and communities, this program declares: we are the architects of our own future.

A Framework for Expansion: What Comes Next?

One successful cohort is a seed. But the real question is how to scale this model.

Here are five recommendations:

- Joint Endowments – HBCUs and African universities should pursue shared endowment vehicles that fund joint programs, scholarships, and research. Such funds would represent a new kind of transatlantic educational capital—independent, mission-driven, and Pan-African in structure.

- Faculty Exchange Pipelines – Beyond student exchanges, institutions must prioritize reciprocal faculty exchange programs. African professors teaching at HBCUs (physically or virtually) and vice versa would broaden curricular offerings and deepen cultural fluency. HBCU Faculty Development Network is the perfect conduit to sponsor the programming infrastructure for such an exchange.

- Shared Research Institutes – HBCUs and African universities could establish co-branded research institutes focusing on themes like climate change, food security, public health, and digital governance—topics where the Global Black experience offers unique insights.

- Diasporic Accreditation Models – One major barrier is credential recognition. A Pan-African accreditation body could facilitate mutual recognition of degrees and allow smoother transitions for students moving between institutions in the Diaspora.

- Government & Philanthropy Engagement – African governments and HBCU-aligned philanthropies must see this kind of partnership as strategic infrastructure. They must fund it accordingly. Every dollar spent here is a dollar spent on self-determination.

The Role of Leadership

Credit must be given where it is due. Dr. Gloria McCutcheon’s work at Claflin demonstrates what it means for faculty to move beyond the classroom and into institution-building. Her leadership not only provided the academic structure for the MS program but built the trust and collaborative framework that such international partnerships demand.

Likewise, Dr. James Salley’s leadership at Africa University—an institution that has long carried the banner of Pan-African Christian higher education—has been instrumental. AU was founded on the principle of serving Africa through excellence, and this collaboration expands that mission into the Diaspora.

This is what visionary leadership looks like: daring to connect what colonialism sought to divide.

The Image as Testament

The image that inspired this article—four young scholars, standing confidently in front of a brick building, adorned in the sunlight of new opportunity—represents more than a graduation. It is a visual declaration of Pan-African potential. Their smiles, their presence, their achievement—each affirms the power of institutions that choose cooperation over competition, legacy over ego, and elevation over exploitation.

They are not just Claflin graduates or Africa University alumni. They are trailblazers of a new academic order—one that transcends borders and builds Black excellence into the very structure of education itself.

Final Thoughts: Pan-African Pedagogy Is The Future

In a century defined by ecological upheaval, technological disruption, and renewed global competition, the African Diaspora cannot afford fragmented institutions. HBCUs and African universities must see each other as natural allies—extensions of a common historical, intellectual, and cultural struggle.

This Claflin-AU partnership is not just a program. It is a model of what is possible when Pan-African Diaspora institutions collaborate with purpose. It is a rejection of dependency and a commitment to capacity-building. It is the beginning of an educational ecosystem rooted in mutual respect, sovereign vision, and Pan-African commitment.

Let it grow. Let others follow. Let this be the future of Pan-African education—intercontinental, interdisciplinary, empowering, and unapologetically transformative.

Congratulations again to the Class of 2025. Your success is our collective success.

#SCUMCConference #elevationandtransformation