Technology is, of course, a double-edged sword. — Alvin Toffler

History does not wait for consensus. The atomic bomb was built before most of the world understood what splitting an atom meant. Chemical weapons were deployed in World War I before international law had language to prohibit them. Surveillance infrastructure was constructed across American cities before most residents knew it existed. In each case, the people most harmed by these technologies were not the people who built them and their eventual objection to the technology, their absence, their refusal to participate did nothing to slow the construction. A weapon being built does not require your approval. It does not require your involvement. It does not even require your awareness. It only requires that someone, somewhere, with sufficient resources and motivation, decided to build it. That is the context in which Black communities must now reckon with artificial intelligence.

Yet in many Black communities and in particular African American institutions, AI is too often treated as a threat to avoid, a fad to dismiss, or a force that is “not for us.” This hesitation is understandable. Black people have learned through painful history that new systems of power often arrive disguised as progress, only to produce new forms of inequality. But the hard truth is this: AI will move forward with or without Black people. And if we choose not to engage it, we guarantee it will be built without our perspective, without our priorities, and without our protection. Rejecting AI does not prevent harm. It only ensures we have less influence over how that harm is shaped and who it harms most.

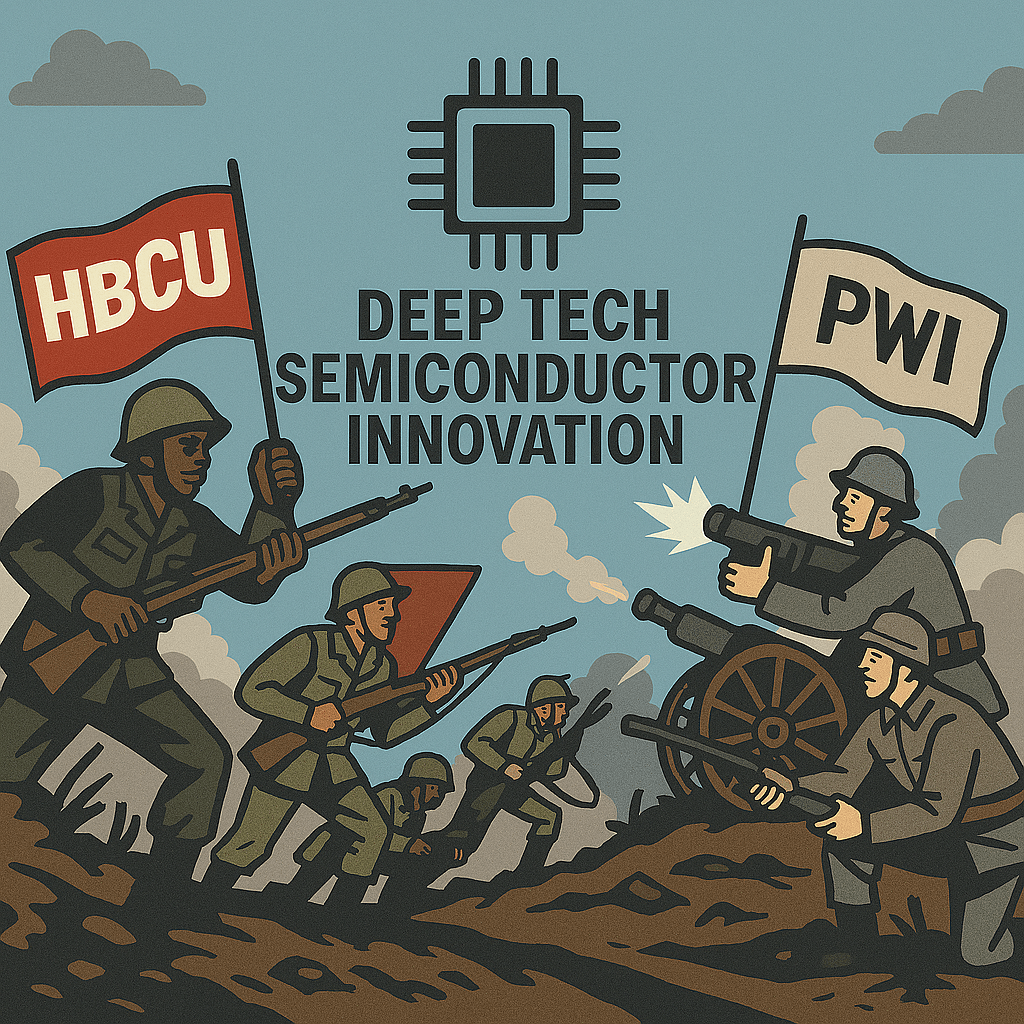

There is a more urgent framing that Black communities must internalize: AI is not merely a tool to be cautious about it is a weapon already being aimed and protest is not a counterattack or defensive strategy. Predictive policing systems profile Black neighborhoods. Hiring algorithms screen out Black applicants. Credit scoring models redline Black borrowers. Facial recognition technology misidentifies Black faces at rates that endanger Black lives. These are not hypothetical risks. They are documented, operational, and expanding. History is clear on what happens when one community monopolizes a powerful weapon while another refuses to pick one up. The answer to a weapon being formed against us is not retreat. It is the development of counterweapons — tools built by us, owned by us, and deployed in the service of our survival and advancement.

This is where the concept of institutional AI ownership becomes essential. Black communities do not simply need AI literacy we need AI proprietorship. We need HBCUs, Black-owned banks, Black medical institutions, Black legal organizations, and Black civic bodies to own the models, the datasets, the patents, and the platforms. Ownership is not the same as access. Millions of Black people access highways they did not design, hospitals that did not include them in clinical trials, and financial systems built to exclude them. Access without ownership is dependency. What this moment demands is that African Americans treat AI the way earlier generations treated land, law, and the ballot as a domain of institutional power that must be claimed, defended, and wielded.

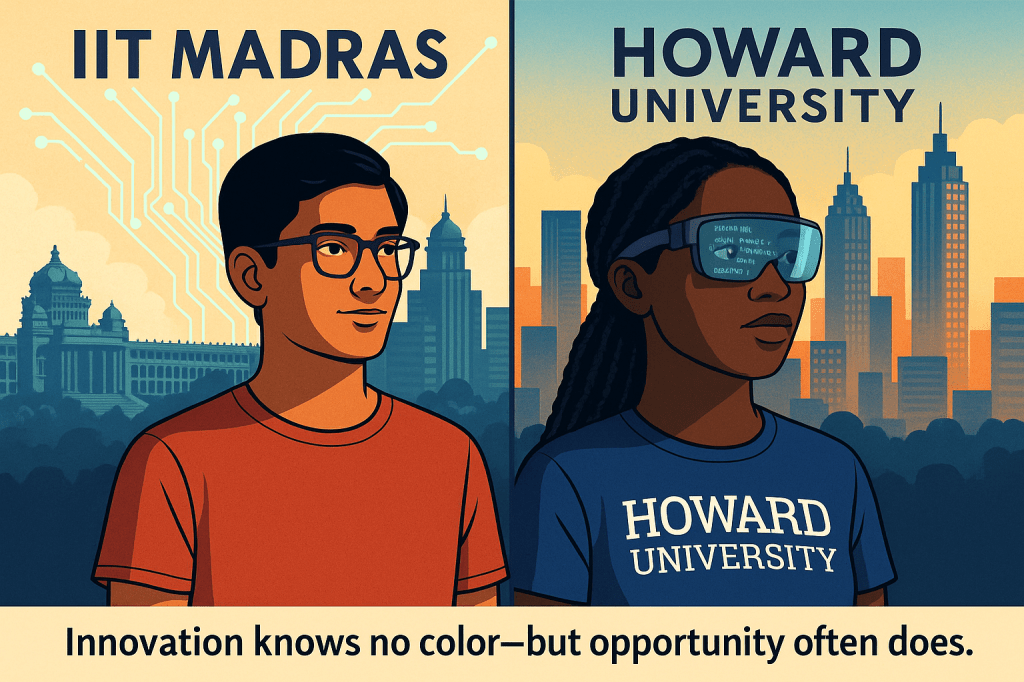

The world is entering a new era of inequality, not one defined by segregation signs or discriminatory laws, but by invisible systems: recommendation engines, automated hiring tools, predictive policing software, medical diagnostic models, financial risk scoring systems, and generative AI. The communities that build these systems set the terms. The communities that merely use them accept them. This is the defining stakes of the AI moment for Black America: not whether to engage, but whether to engage as subjects or as sovereigns.

There is growing sentiment among skeptics that AI is too dangerous to embrace, and some advocate banning or severely limiting it. While a ban is unrealistic, the concerns behind that sentiment deserve to be treated seriously — not mocked, not dismissed, and not ignored. Many Black Americans are concerned that AI is accelerating misinformation and destabilizing trust in public institutions. Deepfakes, AI-generated propaganda, and synthetic news content can manipulate elections and distort civic discourse. For communities that have historically been targeted by voter suppression and political disinformation, this fear is not paranoia it is rational. If AI becomes a weapon of influence, communities already vulnerable to manipulation will be the first casualties. But the problem is not AI itself. The problem is who controls AI and how it is regulated. If Black communities opt out of our own AI development, then AI governance will be decided entirely by other groups with minimal Black representation at the tables where the rules are written. The answer is not simply to lobby for better regulation, though that matters. The deeper answer is to build Black-owned AI systems that are structurally incapable of being weaponized against Black communities because we designed them, we trained them, and we control them. You do not neutralize a weapon aimed at you by asking its owner to be more careful. You build a counterweapon of your own.

Many critics argue that AI encourages intellectual laziness. If students can generate essays instantly and professionals can automate tasks with a click, what happens to discipline, creativity, and hard-earned expertise? This concern is valid. Overdependence on AI can weaken critical thinking, reduce originality, and blur accountability. But it also misses a key historical reality: tools have always replaced certain forms of labor. Calculators did not destroy mathematics. Spellcheck did not destroy writing. The internet did not destroy learning it changed how learning happens. AI is simply the newest tool. The question is not whether AI makes people lazy. The question is whether we are teaching people to wield it with intention. HBCUs must build education models that go beyond productivity training, that teach students not how to use AI as a shortcut, but how to build with it, own it, and direct it toward the problems that matter most to Black communities.

Job displacement is one of the most serious fears in the Black community, and for good reason. Black workers are disproportionately represented in industries vulnerable to automation — retail, transportation, customer service, clerical work, and entry-level administrative jobs. Many of these roles are prime targets for AI replacement. But the response cannot simply be to train Black workers to fill the lower rungs of someone else’s AI economy, to become the new labor class servicing infrastructure we do not own, feeding data into systems we did not build, and executing decisions made by algorithms we cannot audit. That is not advancement. That is a more sophisticated version of the same arrangement. The goal must be ownership: of the companies building AI, of the models being trained, of the intellectual property being filed, of the venture funds writing the checks. HBCUs must orient their graduates not toward employment in the AI industry but toward founding it. The difference between a Black workforce that operates AI and a Black community that owns AI is the difference between wages and wealth and that distinction will compound across generations.

A major criticism of AI is that it consumes enormous energy. But an even less discussed reality is that AI consumes enormous amounts of water. Modern AI runs on massive data centers that require constant cooling to prevent overheating. Many of these facilities rely on water-based cooling systems that consume millions of gallons annually. Researchers estimate that training a single large AI model can consume hundreds of thousands of gallons of water when factoring in data center cooling demands and electricity generation. This is not theoretical. In many regions facing droughts or water restrictions, data centers are consuming water at industrial levels while residents face conservation mandates. But embedded in this crisis is one of the most significant entrepreneurial opportunities of the next two decades. The AI industry desperately needs breakthroughs in energy-efficient computing, low-heat chip architecture, passive and liquid cooling innovation, and renewable-powered data infrastructure. These are not solved problems they are open problems, and open problems are where fortunes and institutions are built. HBCUs are uniquely positioned to lead here. Engineering and computer science programs at HBCUs can orient entire research agendas around sustainable AI infrastructure, competing for federal grants, Defense Department contracts, and private R&D investment. The students and faculty who crack these problems will not simply publish papers they will file patents, spin off companies, and own the solutions the entire AI industry will have to buy. The energy crisis of AI is not just a threat to communities bearing its environmental cost. For those with the vision to pursue it, it is an invitation to build the next generation of technology companies from the inside of an HBCU lab.

Even more troubling is the emerging pattern of where these data centers are being built. Across the U.S., data centers are increasingly constructed in areas that are cheaper to build in, politically weaker, under-resourced, historically undervalued, and disproportionately Black. This mirrors a long-standing trend in America where environmentally burdensome infrastructure — highways, factories, waste facilities gets placed near Black neighborhoods. In effect, this creates what some advocates now call “AI redlining.” The benefits of AI from profits, corporate growth, stock market gains are extracted upward, while the environmental strain gets dumped into communities with the least political power to resist it. The solution is not to reject AI. If Black communities sit out the AI revolution, we won’t stop the environmental cost. We will simply lose the ability to negotiate where that cost is placed and who gets compensated. African American institutions should push for policies requiring mandatory water usage disclosure, environmental impact assessments before zoning approval, sustainability audits, green cooling requirements, and renewable energy sourcing. Communities should demand Community Benefit Agreements requiring data centers to provide infrastructure investment, local hiring pipelines, job training programs, tax revenue reinvestment into local schools, and environmental mitigation funding. HBCUs could also lead the nation in Green AI research, building intellectual property around sustainable computing, energy-efficient AI, and water-saving data center technologies.

The most dangerous thing happening right now is not that Black people fear AI. It is that too many are dismissing it without building anything in its place. Fear without construction is just surrender by another name. If we do not develop our own research institutions, our own datasets, our own models, and our own policy arguments, we cede every seat at every table where AI’s future is being decided. Other communities are not waiting. They are filing patents, training models, lobbying legislatures, and writing the rules. Our absence is not neutrality. It is forfeiture.

Nowhere is that forfeiture more consequential than in healthcare. Black people face notorious disparities in outcomes — maternal mortality, hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, cancer detection delays, and mental health underdiagnosis. AI has the potential to improve diagnostics, predict risk earlier, and increase efficiency. But AI only works equitably if the data used to train it includes accurate representation of Black populations. If Black communities are underrepresented in healthcare datasets, AI tools will misdiagnose and under-detect conditions in Black patients not out of malice, but out of absence. Black maternal mortality runs roughly two to three times higher than that of white women. That gap will not close by using someone else’s model. It will close when Black medical institutions are building their own. HBCUs should establish AI healthcare research centers and partner with Black hospitals and clinics to develop maternal health monitoring tools, diagnostic models trained on Black patient datasets, and predictive systems for chronic disease management. We cannot outsource our survival to someone else’s dataset.

One reason economic inequality persists is because the Black community often lacks robust data infrastructure. We need AI to better analyze Black household wealth gaps, credit access patterns, housing appraisal disparities, small business loan outcomes, and generational income mobility. Without strong data, we cannot make powerful arguments in policy spaces. Decisions get made based on incomplete or misleading statistics. If you cannot measure injustice, you cannot prove it. And if you cannot prove it, you cannot correct it. AI tools can allow Black institutions to build community-level dashboards for employment trends, entrepreneurship activity, housing discrimination patterns, and lending disparities. If we don’t build this infrastructure, we remain dependent on outsiders to define our economic reality.

Black students face disparities in standardized testing, school funding, disciplinary action, access to advanced coursework, and teacher turnover rates. AI has the potential to identify patterns that human analysis often misses. AI models can detect whether certain districts disproportionately suspend Black students or deny gifted program access but this only happens if someone is collecting and analyzing the data. HBCUs can create AI education labs focused on predictive models for dropout prevention, tutoring systems for underserved schools, bias detection in school disciplinary systems, and literacy and math intervention tools.

The ownership imperative extends beyond economics into culture, politics, and identity itself. AI is being trained on datasets that misinterpret Black culture, Black dialect, and Black history. Systems routinely fail to understand African-American Vernacular English and mislabel it as incorrect or unprofessional. If Black people are not involved in building the systems that process human language, cultural misrepresentation does not just persist it gets automated, scaled, and encoded as objective truth. Politically, AI will increasingly govern voter outreach, campaign strategy, political advertising, and law enforcement surveillance. A community without ownership in those systems is a community being governed by algorithms it cannot see, challenge, or correct. And economically, the greatest wealth-building opportunities of the next 20 years will flow from AI ownership — patents, startups, data assets, and proprietary platforms. The next generation of billionaires will not come from oil. They will come from algorithms. The question is whether any of them will come from HBCUs.

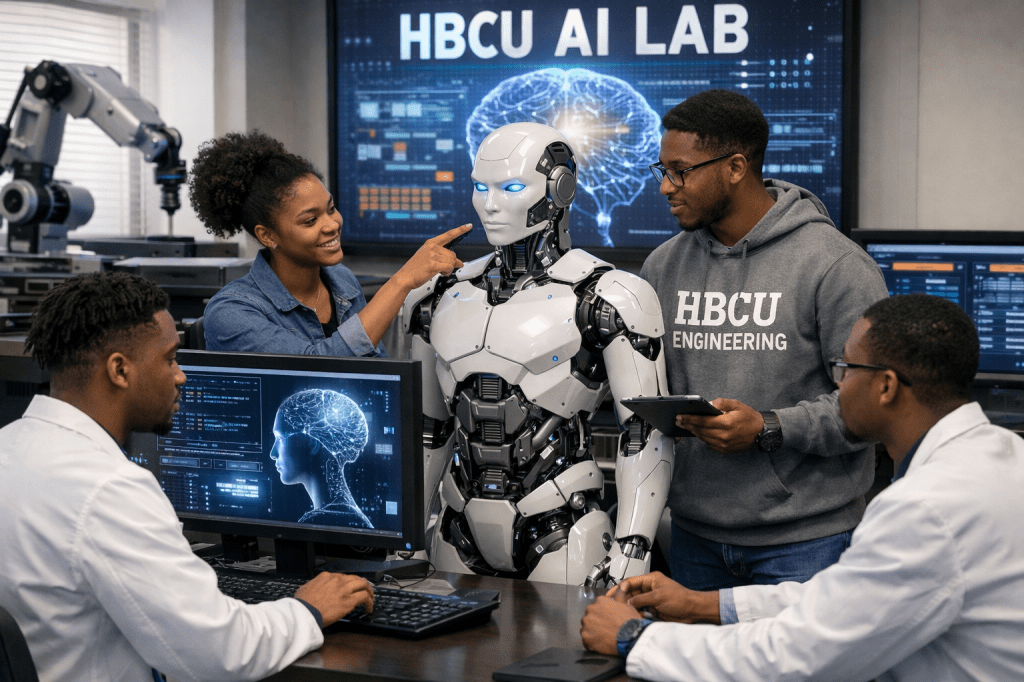

One of the most clarifying facts in this debate is this: HBCU students are not rejecting AI. They are already using it. Surveys show AI adoption among HBCU students above 90% in some reports. The problem is not resistance. The problem is that students are using AI as a consumer product while their institutions have not yet equipped them to build, own, or direct it. There is no AI curriculum grounded in Black ownership. There are no research labs generating Black-controlled intellectual property. There are no institutional frameworks teaching students that the goal is not to get a job at an AI company it is to found one. We are handing students a weapon and teaching them to hand it back.

The solution is not to shame dissenters or pretend AI is harmless. The solution is to build a structured response that combines caution with action. AI should be taught at HBCUs not as an elective but as a foundational literacy, like writing or math. Rather than each HBCU fighting alone, they could form a national consortium to share computing infrastructure, datasets, research funding, and faculty development programs. HBCUs should expand incubators focused on AI startups, fintech and credit access tools, healthcare AI apps, education platforms, and legal justice tools. Black communities should lead in shaping ethical AI laws requiring bias audits, explainability standards, civil rights protections, and anti-surveillance restrictions. And the community must prioritize ownership of data, because data is the oil of the AI economy. If Black communities do not own their datasets, they will never fully control the systems built from them.

If HBCUs want to remain relevant not just historically, but economically and politically in the next 50 years they must move aggressively on a clear ownership agenda. In the first 12 months, every student regardless of major should graduate with AI literacy training, prompt engineering fundamentals, AI ethics coursework, and data verification and misinformation training. Each institution should form an internal AI Ethics Board including faculty, students, alumni in tech, legal experts, and community leaders to oversee how AI is adopted on campus and how students are trained to deploy it with intention. A required AI Skills Certificate open to all majors should cover Python basics, data analytics, machine learning foundations, and the fundamentals of building and launching AI-powered ventures. Over the following two years, HBCUs should build a shared computing consortium that supports AI research, student projects, and community-owned datasets — infrastructure that belongs to the network of Black institutions, not to any outside vendor. Every HBCU should prioritize building pipelines into Black-owned and Black-led technology ventures first feeding talent back into institutions the community controls. Where partnerships with larger tech companies, healthcare systems, federal research agencies, and defense and cybersecurity programs are pursued, they must be negotiated on terms that preserve IP ownership, protect student data, and create reciprocal investment in HBCU infrastructure not simply pipelines that funnel Black talent into someone else’s institution and call it progress. Each school should develop a startup incubator focused on AI healthcare tools, fintech solutions, education technology, environmental AI monitoring, and civil rights auditing software — companies built to be owned, not just to be acquired.

Over the longer horizon of three to ten years, HBCUs must focus on patents, proprietary research, and scalable tools — not just academic publications. They should become national voices shaping AI governance, civil rights protections, workplace automation policy, data center zoning laws, and environmental justice in AI infrastructure. And by partnering with alumni and Black-owned banks to create a venture fund investing in student startups, faculty innovations, and Black AI entrepreneurs, HBCUs can ensure that the wealth generated by AI does not pass Black communities by entirely.

The Black community has every right to be skeptical of new systems of power. History proves that skepticism is justified. But skepticism is not a strategy and caution is not a counterforce. If a weapon is being formed against us, and the evidence is overwhelming that it is, then we are obligated to form counterweapons. We are obligated to build AI systems that protect Black neighborhoods from surveillance overreach, that audit algorithms for racial bias, that train on Black medical data to save Black lives, that document economic discrimination and place it irrefutably before courts and legislatures. We are obligated to claim institutional ownership of this technology not as guests in someone else’s ecosystem, but as architects of our own. AI will shape the future of medicine, education, business, culture, and governance. The most dangerous outcome is not that AI exists. The most dangerous outcome is that it exists without us and for others to use against us. The future is being coded right now. We must be on the playing field. We must hold the pen.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ClaudeAI.