“Control of credit is control of destiny. Until Our institutions decide where Our capital sleeps and wakes, Our freedom will remain on loan.” – William A. Foster, IV

The African diaspora’s greatest unrealized financial potential may lie not in Wall Street, but in the vast and growing debt markets of Africa. Across the continent, nations are negotiating, restructuring, and reimagining how they fund development. At the same time, African American banks and financial institutions, small but strategically positioned in the global Black economic architecture, stand largely on the sidelines. This disconnection is more than a missed investment opportunity; it is a failure of transnational financial imagination. If the descendants of Africa in America wish to secure true sovereignty, interconnectivity, and global influence, engaging African debt markets is not optional it is imperative.

Africa’s debt profile is as complex as it is misunderstood. Many Western narratives frame African debt in crisis terms, yet that view ignores the sophistication of African capital markets and the diversity of creditors. The continent’s public debt stood around $1.8 trillion by 2025, but much of this borrowing has gone toward infrastructure and industrial expansion. The key shift in recent years has been away from traditional multilateral lenders toward bilateral and market-based finance particularly through Chinese, Gulf, and private bond markets. Countries like Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, and Ethiopia have issued Eurobonds in recent years, often at higher interest rates due to perceptions of risk rather than fundamental insolvency. Others, such as Zambia, have undergone restructuring efforts designed to rebalance repayment with growth. In each case, Africa’s economic story remains one of ambition constrained by external debt conditions, a pattern reminiscent of the post-Reconstruction era Black South, when capital starvation and dependency on non-Black lenders limited autonomy and intergenerational power. That parallel matters deeply for African Americans. The same global financial order that restricts African nations’ fiscal independence also limits the growth of African American financial institutions. The tools that could change both realities already exist within the diaspora: capital pools, credit analysis expertise, and shared strategic interest in sovereignty.

African American banks—roughly 18 federally insured institutions as of 2025—control an estimated $6.4 billion in combined assets. While that is a fraction of what one mid-sized regional white-owned bank manages, these institutions hold a symbolic and strategic power far greater than their balance sheets suggest. They remain the custodians of community trust, the anchors of small-business lending in historically neglected markets, and potential conduits for international financial collaboration. Historically, African American banks were created to fill a void left by exclusionary financial systems. But in the 21st century, their mission can evolve beyond domestic community lending toward global financial participation. The African debt market, currently dominated by Western institutions that extract value through high interest and credit rating manipulation, offers a natural arena for African American engagement. If Black banks can collectively participate through bond purchases, underwriting partnerships, or diaspora-focused sovereign funds they could help shift Africa’s dependence from Western and Asian creditors toward diaspora-based capital flows. This would not only stabilize African economies, but also create transnational linkages that reinforce both African and African American economic self-determination.

Consider the power of mutual indebtedness as a political tool. When nations or institutions lend to each other, they form durable relationships governed by trust, negotiation, and shared interest. For too long, the African diaspora’s relationship with Africa has been philanthropic or cultural rather than financial. That model, however well-intentioned, is structurally disempowering and it reinforces dependency rather than partnership. Debt, properly structured, reverses that dynamic. If African American financial institutions were to purchase or underwrite African sovereign and municipal debt, they would create financial obligations that tether African states to diaspora capital, not to exploit but to interdepend. This is the foundation of modern sovereignty: the ability to borrow and invest within your own cultural and political network rather than through intermediaries who extract value and dictate terms. Imagine, for instance, a syndicated loan or bond issuance where a consortium of African American banks, credit unions, and philanthropic financial arms partner with African development banks or ministries of finance. The terms could prioritize developmental outcomes like affordable housing, small business lending, renewable energy while generating steady returns. The instruments could even be marketed domestically as “Diaspora Sovereign Bonds,” accessible through digital platforms. The impact would be twofold: African American banks would diversify their portfolios and tap into emerging market yields, while African governments would gain access to capital free from neocolonial conditions.

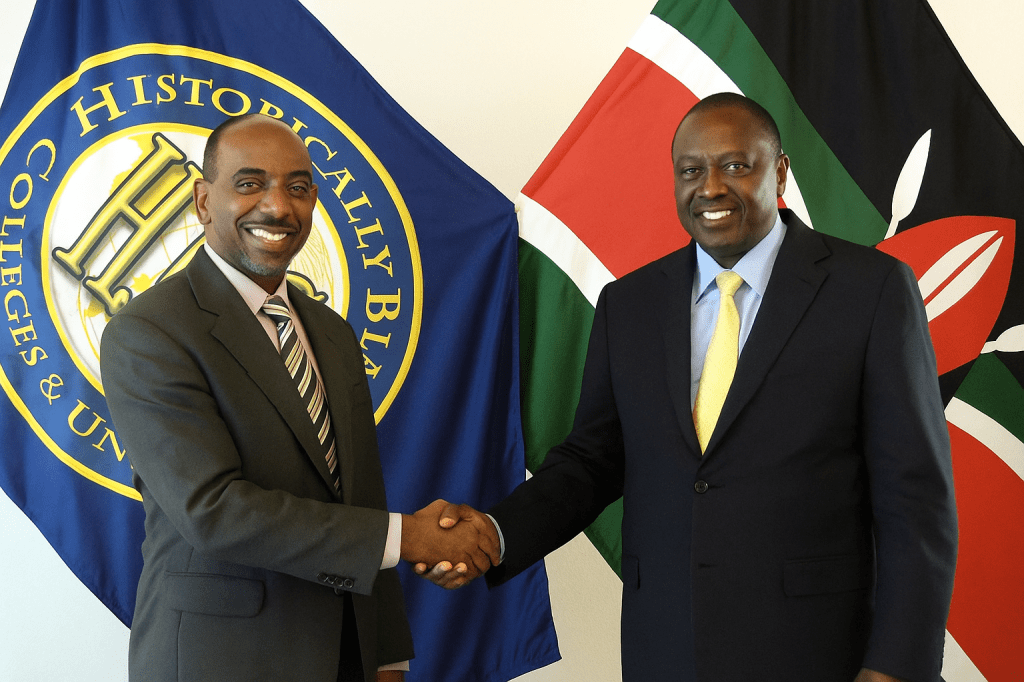

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) stand at the crossroads of intellect, finance, and heritage. Their institutional capacity, academic talent, and alumni networks make them natural architects for a new financial relationship between the African diaspora and the African continent. Yet this potential comes with risk, particularly for public HBCUs, whose visibility and state dependency could make them targets of political and financial backlash. If a public HBCU were to openly participate in or advocate for engagement with African debt markets, it would likely face scrutiny from state legislatures, regulatory bodies, and entrenched financial interests. Such activity would be perceived by non–African American–owned banks and state-level policymakers as a challenge to existing capital hierarchies. The idea of Black public institutions developing transnational financial alliances outside traditional Western frameworks threatens not only market control but ideological narratives about where and how Black institutions should operate. To navigate this terrain, public HBCUs must be strategic, creative, and stealth in execution. Their participation in African financial engagement cannot be loud; it must be layered. They can do so through consortia, research collaborations, and investment partnerships that quietly build expertise and influence without triggering overt resistance. For example, an HBCU economics department could conduct African sovereign credit research under a global development initiative, while a business school could host “emerging market” investment programs that include African debt instruments without explicitly branding them as Pan-African.

Private HBCUs, freer from state oversight, can play a more overt role forming partnerships with African banks, hosting diaspora finance summits, and seeding funds dedicated to Africa-centered investments. But public institutions must operate with a subtler hand, leveraging think tanks, foundations, and alumni networks to pursue the same ends through indirect channels. Creativity will be their shield. Collaboration with African American–owned banks, credit unions, or diaspora investment funds can serve as intermediary structures allowing HBCUs to channel research, expertise, and even capital participation without placing the institutions themselves in direct political crossfire.

Both public and private HBCUs must also activate and empower their alumni associations as extensions of institutional sovereignty. Alumni associations exist in a different legal and political space and they are often registered as independent nonprofits, free from the direct control of state governments or university boards. This autonomy allows them to operate where the universities cannot. Through alumni associations, HBCUs can channel capital, intelligence, and partnerships in ways that stay outside the reach of regulators or political gatekeepers. Alumni bodies can create joint funds, invest in African debt instruments, or collaborate with African banks and diaspora enterprises. The understanding between HBCUs and their alumni networks must be clear and disciplined: the institution provides intellectual and structural guidance; the alumni associations execute the capital movement. This relationship becomes a discreet circulatory system of sovereignty with universities generating the vision and expertise, alumni executing the financial maneuvers that advance that vision.

HBCUs can further support this ecosystem by funneling institutional capital and intellectual property toward their alumni associations in strategic, deniable ways. Research centers can license data or consulting services to alumni-managed firms. Endowments can allocate small funds to “external collaborations” that, in practice, seed diaspora initiatives. Career and alumni offices can quietly match graduates in finance and development with African institutions seeking diaspora partners. These are small, legal, but potent acts of quiet nation-building. The success of this strategy depends on discipline, secrecy, and shared purpose. HBCUs, particularly the public ones, must move as institutions that understand the historical realities of Black advancement: every act of power must be both visionary and shielded. Alumni associations, meanwhile, must operate as the agile extensions of these universities, taking calculated risks on behalf of the larger mission. If executed carefully, this dual structure of HBCUs as the intellectual architects and alumni associations as the financial executors creates a protected channel for diaspora wealth creation. It allows public institutions to avoid political exposure while still advancing the collective objective: redirecting Black capital toward Africa and reestablishing a financial circuit of trust, obligation, and empowerment across the diaspora. In this model, the public HBCU becomes the hidden engineer, the private HBCU the visible vanguard, and the alumni network the financial hand. Together, they form an ecosystem of quiet innovation and a movement that builds transnational Black sovereignty not through protest or proclamation, but through precise and deliberate financial design.

Skeptics might argue that African American banks lack the scale or technical capacity to engage in sovereign lending. This concern, while not unfounded, can be addressed through collaboration. No single Black institution must go it alone. The path forward lies in consortium models of pooling resources, sharing risk, and leveraging collective bargaining power. Diaspora bond funds could be structured as partnerships between African American banks, HBCU endowments, and African development finance institutions such as the African Development Bank (AfDB) or Africa Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank). These organizations already have experience managing sovereign risk and would benefit from diaspora participation, which strengthens their political legitimacy. Furthermore, technology has lowered the cost of entry into complex financial markets. Digital banking, blockchain-based identity verification, and fintech partnerships can allow diaspora institutions to participate in cross-border finance with greater transparency and speed. The real obstacle, therefore, is not capacity it is vision. The diaspora’s capital remains trapped within Western financial systems that reward liquidity but punish sovereignty. Redirecting even a fraction of that capital toward Africa would shift the balance of global economic power in subtle but profound ways.

Sovereignty in the modern world is measured as much in capital access as in military or political power. Nations that cannot borrow on fair terms cannot build on fair terms. The same is true for communities. African Americans, long denied fair access to capital, should understand this truth intimately. The African debt question, then, is not a distant geopolitical matter it is a mirror. If African American banks and financial institutions continue to operate solely within the parameters of domestic credit markets, their growth will remain capped by a system designed to contain them. But if they extend their vision outward to the African continent, to Caribbean nations, to the global diaspora then they create new asset classes, new partnerships, and new pathways to power. Moreover, engagement with African debt markets enhances geopolitical influence. It positions African American institutions as interlocutors between Africa and global finance, enabling a collective voice on credit ratings, debt restructuring, and investment policy. That is the kind of influence that cannot be achieved through philanthropy or symbolism it is built through transactions, treaties, and trust.

Other diasporas have already proven this model works. Jewish, Indian, and Chinese global networks have long used financial interconnectivity as a tool of sovereignty. Israel’s government issues bonds directly to diaspora investors through the Development Corporation for Israel—a program that has raised over $46 billion since 1951. The Indian diaspora contributes billions annually in remittances and investments that underpin India’s foreign reserves. The African diaspora, by contrast, remains financially fragmented despite its vast size and income. With over 140 million people of African descent living outside Africa, the potential for coordinated capital deployment is immense. Even modest participation of say, $10 billion annually in diaspora-held African bonds would change the global conversation around African finance and diaspora economics. This scale of engagement requires trust, transparency, and accountability. African nations must commit to governance reforms and anti-corruption measures that assure diaspora investors of integrity. Likewise, African American institutions must build financial literacy and confidence around African markets, overcoming decades of Western media narratives portraying the continent as unstable or uninvestable.

The long-term vision is a self-sustaining ecosystem of diaspora credit: African American and Caribbean banks pool capital to buy or underwrite African debt; HBCUs model sovereign risk, publish credit analyses, and design diaspora finance curricula; African governments and regional banks issue diaspora-oriented financial instruments; fintech platforms connect diaspora investors directly to African projects; and cultural finance diplomacy transforms diaspora engagement into official national strategy. The ecosystem would allow wealth to circulate within the global African community rather than being siphoned outward through exploitative intermediaries. Over time, such networks could support not only debt financing but also equity investment, venture capital, and trade finance all under the umbrella of Black sovereignty economics.

At its core, this initiative is not merely about money. It is about the reconfiguration of power. The African diaspora cannot achieve full sovereignty while its economic lifeblood flows through institutions indifferent or hostile to its future. Engaging African debt markets transforms the diaspora from spectators of African development into its co-architects. It also transforms Africa from a borrower of last resort to a partner of first resort within its global family. For African American banks, this is the logical next chapter. The institutions that once shielded Black wealth from domestic exclusion now have the opportunity to project that wealth into international inclusion. It is a matter of strategic foresight aligning moral mission with financial opportunity. As the world edges toward a multipolar order where the U.S., China, and regional blocs vie for influence, the African diaspora must define its own sphere of power not through slogans but through balance sheets. A sovereign people must have sovereign finance.

Toward a Diaspora Credit Ecosystem

The long-term vision is a self-sustaining ecosystem of diaspora credit:

- Diaspora Banks & Funds: African American and Caribbean banks pool capital to buy or underwrite African debt.

- HBCU Research Hubs: HBCUs model sovereign risk, publish credit analyses, and design diaspora finance curricula.

- African Institutions: African governments and regional banks issue diaspora-oriented financial instruments.

- Fintech Platforms: Secure, regulated digital systems connect diaspora investors directly to African projects.

- Cultural Finance Diplomacy: Diaspora engagement becomes part of national policy—similar to how nations court foreign direct investment today.

The ecosystem would allow wealth to circulate within the global African community rather than being siphoned outward through exploitative intermediaries. Over time, such networks could support not only debt financing but also equity investment, venture capital, and trade finance all under the umbrella of Black sovereignty economics.

In 1900, at the First Pan-African Conference in London, W.E.B. Du Bois declared, “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.” A century later, that color line has become a credit line. It is drawn not only across borders but across ledgers between who lends and who borrows, who owns and who owes. The African American bank and the African treasury are not distant cousins; they are parts of one economic body severed by history and waiting to be reconnected by will. Engaging African debt markets is not charity it is strategy. It is the financial expression of unity long preached but rarely practiced. The next stage of the African world’s freedom struggle will not be won merely in the streets or in the schools. It will be won in the boardrooms where capital chooses its direction. If African American finance chooses Africa, both sides of the Atlantic will rise together not as debtors and creditors, but as partners in sovereignty.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.