“We don’t need to break ground to build power. Sometimes we just need to reclaim it.” – HBCU Money

In the 1990s and early 2000s, no suburban corner in America seemed complete without a modest retail strip: a nail salon, dry cleaner, small grocer, and maybe a local pizza joint. These seemingly unremarkable centers were the backbone of everyday commerce. Then came e-commerce, big box expansions, and shifting consumer behavior. The strip center fell out of fashion until now.

Today, those vintage retail strip centers are experiencing a renaissance. Commercial real estate investors, faced with skyrocketing construction costs and restrictive lending environments, are rediscovering the power and profitability of renovating existing assets. For HBCU alumni investors looking to blend stable returns with community impact, this moment presents a rare convergence of opportunity, efficiency, and cultural relevancy.

The Math Behind the Momentum

Construction costs for new retail buildings are ballooning. Estimates now range from $250 to $300 per square foot for ground-up construction sometimes higher in urban markets. At those prices, generating attractive returns is difficult unless you’re building luxury, destination retail with national anchor tenants. That’s not where the market is heading.

Instead, investors are realizing they can acquire and renovate vintage strip centers typically 20 to 40 years old for far less than the cost of new construction. Many are structurally sound but aesthetically dated or functionally obsolete. These properties often sit on prime real estate near transportation corridors, residential growth areas, or college campuses including HBCUs.

When repositioned with the right tenants, lighting, signage, and facades, vintage centers can achieve competitive rents without incurring the deep capital exposure of new construction. They offer a rent-to-cost ratio that works, especially in secondary and tertiary markets where demand for accessible neighborhood retail remains strong.

A Platform for Black Wealth Creation

For HBCU alumni who have traditionally been boxed out of Class A urban development deals, vintage strip centers represent an asset class that is:

- Financially accessible

- Culturally significant

- Commercially viable

Most importantly, these assets can serve as anchors for Black-owned businesses, co-ops, and cultural hubs. While institutional investors often chase high-profile multifamily or office deals, retail strip centers in historically Black communities or near HBCUs are often overlooked providing a wedge for local or regional investors to step in.

A well-structured renovation project led by an HBCU graduate could transform a decaying strip into a vibrant ecosystem of barbershops, cafés, health providers, financial institutions, and coworking spaces all backed by the community, for the community.

Deferred Maintenance as Opportunity, Not Obstacle

Critics of strip centers often cite “deferred maintenance” as a red flag. And it’s true—many of these assets come with leaky roofs, outdated HVAC systems, and non-compliant ADA access. But that doesn’t make them unviable. It makes them undervalued.

Roof replacements, ADA compliance upgrades, lighting retrofits, parking lot resurfacing—these are all predictable costs that can be priced and phased. Investors willing to do their homework (or partner with experienced contractors) can use these improvements to negotiate purchase price reductions while still bringing total project costs well below new-build levels.

The essential formula is: fix what’s failing, elevate what’s usable, reimagine what’s tired. A fresh coat of paint and new signage can do wonders. Add in a few placemaking enhancements—like patio seating, bike racks, or public art and you’ve turned an afterthought into a destination.

The Tenant Mix Advantage

Unlike enclosed malls or big-box centers, strip malls thrive on tenant diversity and flexibility. This is where Black investors especially HBCU alumni with deep community ties—can bring unique vision.

Think beyond the nail salon and dry cleaner. Consider:

- Black-owned coffee shops sourcing from Black farmers

- Culinary incubators for emerging chefs and caterers

- Financial coaching centers led by HBCU grads

- Community health or dental clinics with wellness services

- Retail cooperatives selling goods from multiple local makers

HBCU alumni investors can fill these strips not just with tenants, but with mission-aligned entrepreneurs. Lease agreements can include mentorship opportunities, cooperative ownership structures, or tenant improvement allowances tied to hiring local workers.

With a thoughtful mix, even a 20,000–30,000 square foot strip center can become an engine of neighborhood stability, economic inclusion, and generational wealth transfer.

Location, Location, Relevance

Vintage strip centers often sit on some of the most undervalued land in America. Many were built decades ago when zoning was looser, and land was cheaper. As communities grow outward and younger generations seek walkable, mixed-use environments those same centers are suddenly back in the middle of activity.

For HBCU alumni, the opportunity is even more focused. There are dozens of strip centers within walking or driving distance of HBCU campuses. Whether it’s off-campus student housing, faculty neighborhoods, or alumni communities, there is demand for:

- Local dining and services

- Affordable, accessible retail

- Safe, well-lit gathering places

- Commercial space for alumni-owned businesses

These are not Class A trophy assets, but they don’t need to be. They need to be functional, familiar, and forward-looking.

Risk and Repositioning

Of course, this isn’t a silver bullet. Not every vintage strip is a diamond in the rough. Investors must do real due diligence:

- Structural Integrity – Always get a full building condition report. It’s the difference between a renovation and a rebuild.

- Zoning Compliance – Changing use (i.e., turning part of a center into residential or entertainment space) may trigger zoning complications or code upgrades.

- Environmental Reviews – Gas stations, dry cleaners, and auto shops may have left behind soil contamination. Budget for testing and potential remediation.

- Tenant Rollover – Inheriting a strip with long-term leases at below-market rents may limit your flexibility.

But with risk comes return. A well-executed repositioning can yield cap rates of 7–9%, with additional upside through refinancing or disposition within 5–10 years.

Financing the Vision

Vintage retail projects are easier to finance than new builds but only if you approach the right lenders. Here’s where HBCU alumni can get creative:

- CDFIs – Community Development Financial Institutions are often more flexible when the project has community benefits.

- Opportunity Zones – Many vintage retail corridors are located in federally designated OZs, allowing access to tax-advantaged equity.

- Historic Preservation Tax Credits – If the building qualifies, you may be eligible for 10–20% of renovation costs back in tax relief.

- Municipal Partnerships – City economic development departments may offer grants, façade improvement programs, or forgivable loans.

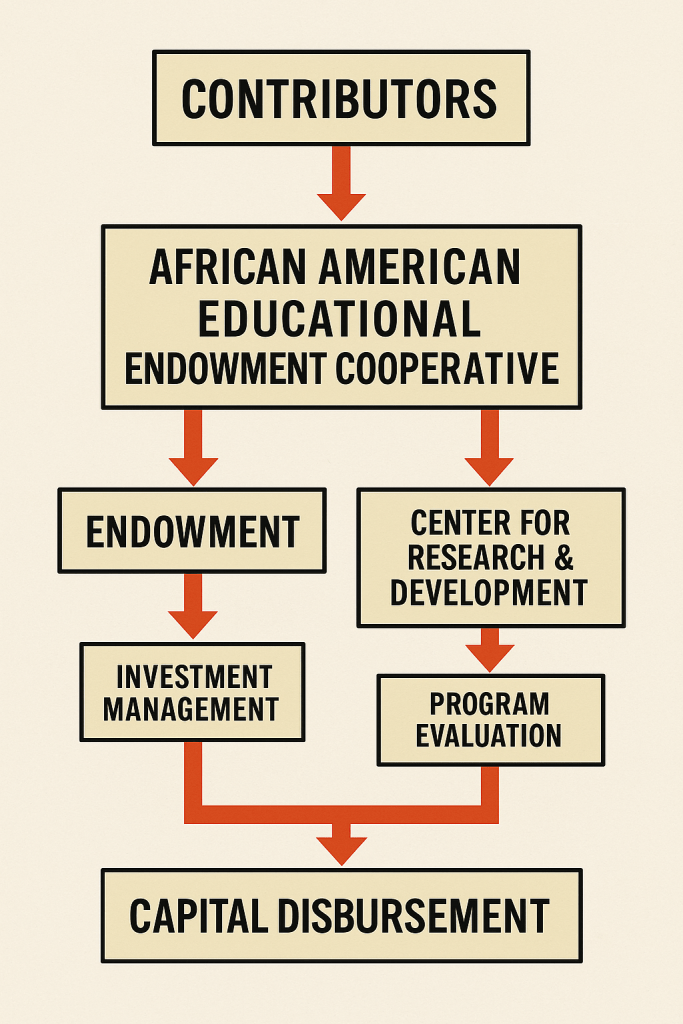

- Alumni Co-Investment Funds – Organize real estate investment clubs or syndicates among HBCU alumni. Use shared mission as shared capital.

A New Generation of Ownership

The big question isn’t whether vintage strip centers are viable. The question is: who will own them?

Will they be scooped up by private equity firms chasing yield? Or will HBCU alumni seize the chance to claim, restore, and transform these assets into hubs of Black entrepreneurship and economic mobility?

Real estate has always been about timing and this is the moment.

If we don’t buy the land, we don’t control the future. But if we do—wisely, collectively, strategically—then a strip center in the shadow of an HBCU can become the foundation of a Black economic dynasty.

Bottom Line

Old retail centers aren’t just retail they are real estate that still works. And right now, they’re one of the most underrated opportunities in commercial real estate.

With vision, planning, and mission-driven capital, HBCU alumni can turn tired retail into thriving centers of community wealth. Not every asset class allows you to be both landlord and legacy builder. But this one does.

The future isn’t always new. Sometimes, it’s renovated.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.