“Philanthropy reflects not just generosity, but power. When African American foundations hold millions while their counterparts hold billions, the capacity to shape society is written in the balance sheets.” – HBCU Money Editorial Board

In the nonprofit and philanthropic world, financial statements tell a story much deeper than annual fundraising drives or program headlines. For African American institutions in particular, the real question of institutional power is not how much money comes in each year, but how much money is working on their behalf every day through investment income. The gap between African American legacy institutions and the nation’s major philanthropic foundations makes this truth impossible to ignore.

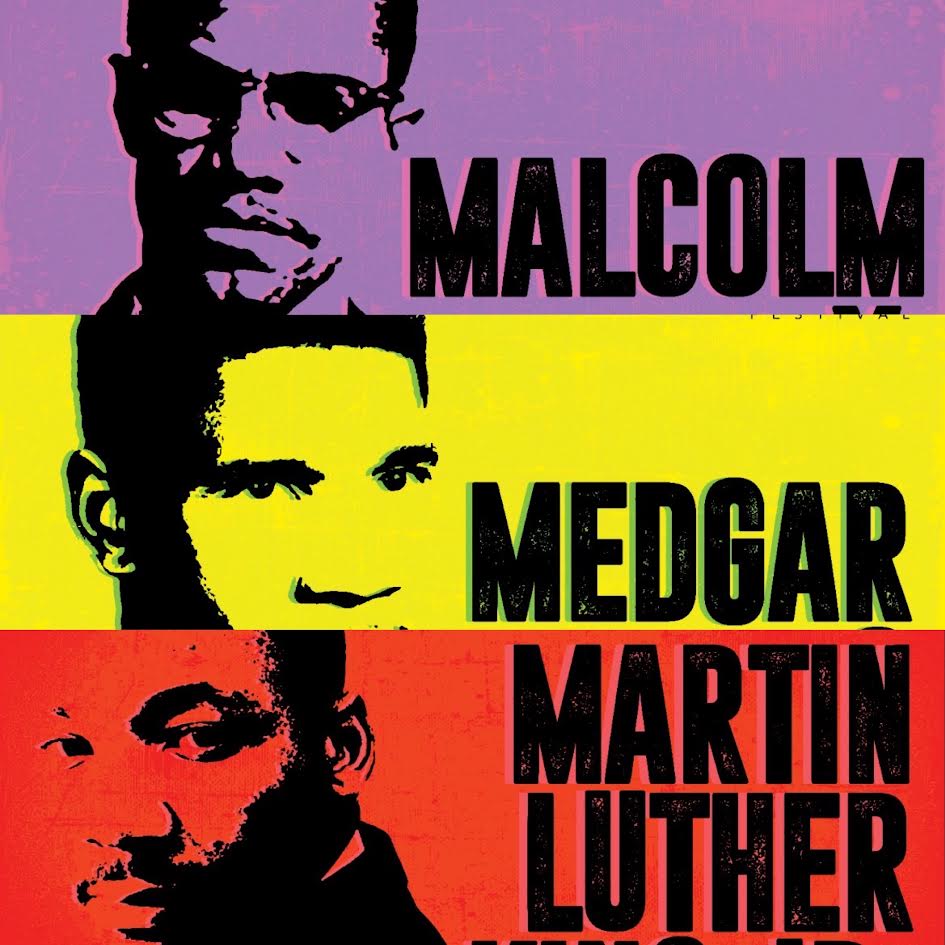

When most people evaluate nonprofits, they look at annual revenue: how much an institution raised in donations, how much it earned from programs, how much it reported on the IRS Form 990. By this metric, many organizations appear healthy. The King Center in Atlanta, for instance, reported $9.1 million in revenue in 2022, and the Malcolm X & Dr. Betty Shabazz Center reported $1.4 million in the same year. Even the Medgar & Myrlie Evers Institute, operating at a much smaller scale, posted $107,000 in revenue in 2023. Yet revenue alone is a deceptive indicator. It measures activity, not stability. Donations can be fickle. Program revenue can evaporate in downturns. Grants can dry up with shifts in political winds. A true measure of institutional health is whether an organization can generate its own independent cash flow — investment income.

The numbers reveal just how stark the divide is. The King Center, the strongest among African American legacy nonprofits, earned $788,000 in investment income in 2022. That represented nearly 9 percent of its total revenue, cushioning its operations with reliable, asset-driven support. By contrast, the Shabazz Center earned just $1,500 in investment income, and the Evers Institute earned nothing at all. Both remain almost entirely dependent on yearly contributions and program dollars. When compared to America’s powerhouse philanthropic institutions, the difference borders on staggering. The Ford Foundation generated $1.2 billion in investment income in 2022 — over 1,500 times what the King Center earned. The Rockefeller Foundation earned $120 million. The Walton Family Foundation, tied to the heirs of Walmart, brought in $240 million. The Bloomberg Family Foundation, anchored by the billionaire media mogul, generated $344 million. In this world, investment income is not supplemental; it is the engine. It underwrites operations, absorbs shocks, and ensures that missions continue even in the absence of donor enthusiasm. Investment portfolios are endowments of power, spinning off influence year after year.

This also clarifies why net income, the difference between revenue and expenses, is often misunderstood as a sign of strength. The King Center ran a $1.28 million surplus in 2022, while the Ford Foundation ran a $520 million deficit. Which institution is stronger? The answer is obvious: Ford. It can afford to run half a billion dollars in the red precisely because it has tens of billions in assets generating massive returns. Its deficit is a choice, not a crisis. By contrast, the Medgar Evers Institute’s deficit of just $25,000 in 2023 threatens its very survival because it has no investment base to fall back on. Net income measures short-term breathing room; investment income measures long-term power.

The contrast becomes sharper when examining the Steward Family Foundation, tied to David Steward, the wealthiest African American man. In 2023, the foundation reported $12.5 million in revenue and $857,000 in surplus, but just $29,000 in investment income. It holds only $22,000 in assets. Despite extraordinary personal wealth, the foundation is structured as a pass-through, distributing annual gifts rather than building a permanent, income-generating endowment. The Steward paradox highlights a broader challenge: African American wealth, even when achieved at extraordinary levels, has not consistently been institutionalized into enduring investment vehicles capable of generating influence across generations.

The implications of this reality are profound. Institutions without investment income are vulnerable to political tides, donor fatigue, and economic downturns. Their missions — whether preserving the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, or Medgar Evers — rest precariously on year-to-year survival. By contrast, the Ford or Rockefeller foundations can guarantee their voices in the public square for centuries. This imbalance in institutional financing means African American causes remain at the mercy of others’ benevolence while rival institutions are powered by their own wealth.

If investment income is the true measure of power, then African American institutions must pursue one clear priority: endowments. Not just annual fundraising, not just program grants, but the deliberate accumulation of assets whose returns will underwrite their missions indefinitely. Imagine if the King Center’s $788,000 in annual investment income could be multiplied tenfold or a hundredfold. Imagine if the Shabazz Center or the Medgar Evers Institute could fund their programming entirely from endowment returns. Imagine if the Steward Family Foundation transformed from a pass-through into a billion-dollar perpetual institution. This is the difference between surviving and shaping the future.

Investment income is the institutional equivalent of compound interest in personal finance. It rewards patience, discipline, and foresight. It separates organizations that merely exist from those that endure. For African American institutions, the lesson is clear: to secure legacies, to project influence, and to build power, they must shift their focus from short-term fundraising to long-term asset building. Only then can African American institutions stand as peers to Ford, Rockefeller, Walton, and Bloomberg — not just in name, but in financial reality.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.