If you think you’re tops, you won’t do much climbing. — Arnold Glasow

Hip-hop was born out of necessity. A sonic rebellion against poverty, violence, and systemic neglect, it emerged from the Bronx as a raw reflection of life in America’s forgotten corridors. But over the past four decades, it has transformed from cultural resistance into commercial royalty. Once recorded with borrowed turntables in community centers, it now echoes across Super Bowl halftime shows, luxury brand campaigns, and billion-dollar corporate balance sheets. Artists who once stood on corners are now seated at boardroom tables. The culture won. But the community did not.

The statistics tell a story of growth at the top and stagnation at the bottom. Hip-hop is now a $16 billion industry. It has created artists turned entrepreneurs who have expanded into liquor, fashion, tech, and sports. The music dominates global charts, sets fashion trends, and influences everything from algorithms to political campaigns. Yet this immense cultural capital has not translated into economic sovereignty for the African American community. Instead, the concentration of wealth in a few hands has often disguised the lack of institutional power. For all the charts conquered and headlines generated, African American banks, endowments, universities, and asset management firms remain modest, if not endangered.

At the heart of this failure lies a devastating contradiction. While rappers flaunt wealth more publicly than any generation before them, the economic conditions in many African American communities remain dire. The median net worth of Black households, as of 2022, stands at $44,100 compared to $284,310 for White households—a gap that has barely moved in decades. Hip-hop has become the most visible face of African American success, but that visibility is not backed by scale. There are no Black equivalents to BlackRock or Vanguard. No hip-hop-funded HBCU research lab. No Goldman Sachs of rap. Even the highest echelon of Black-owned investment firms manage a fraction of their white counterparts. Vista Equity Partners, the most prominent, oversees $103.8 billion, an extraordinary feat, yet still a rounding error next to BlackRock’s $10.5 trillion.

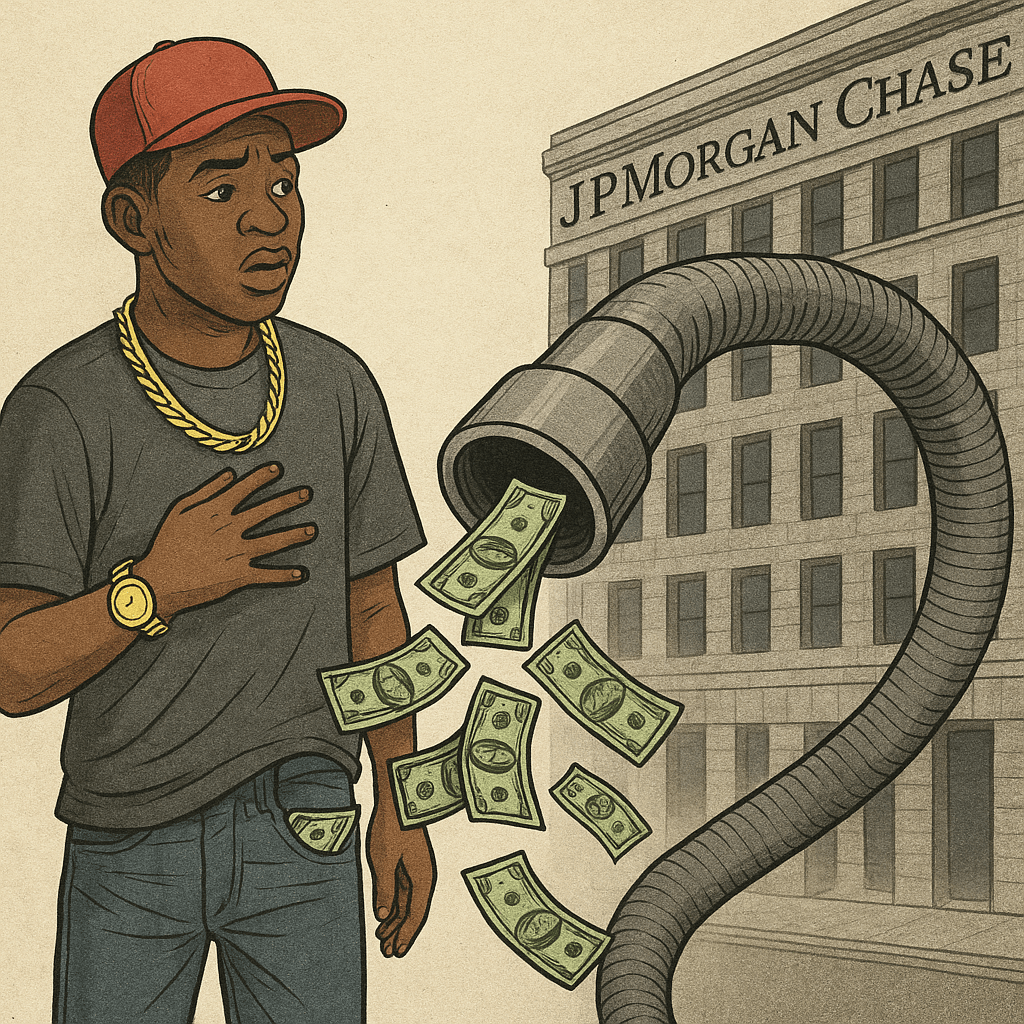

And even this level of institutional success is an outlier. Most Black-owned investment firms manage less than $10 billion. Most HBCUs have endowments below $50 million. The largest Black bank, OneUnited, holds roughly $650 million in assets, while Bank of America manages over $2.5 trillion. What hip-hop has delivered in influence, it has not delivered in capital. Instead of building institutions, it has made individuals rich. But those individuals exist within a system that continuously siphons wealth away from their communities.

This is not to say that artists bear the blame for economic injustice. But hip-hop has become a tool of seduction as much as expression. Its dominance in the global marketplace has aligned it with the poor man’s logic of capitalism celebrating consumption, rewarding individualism, and elevating spectacle. In this model, buying a Bugatti becomes a symbol of power, while the absence of a Black mutual fund managing $100 billion barely registers. Lyrics obsess over fashion houses like Balenciaga, but rarely name Black-owned real estate firms or venture capital funds. The dream has shifted from ownership of blocks to ownership of Birkin bags.

This performative wealth is not just cultural; it’s systemic. The music industry itself is structured to extract more than it distributes. Record labels, streaming services, and publishing houses are disproportionately owned by entities with no allegiance to Black institutions. A 2023 report by Rolling Stone noted that artists receive less than $0.004 per stream on major platforms. Even when a track is streamed millions of times, the majority of profits flow to tech firms and record conglomerates, not to the creators or their communities. The money flows up and out. It is the same pattern that defines the broader African American economic experience: labor and creativity are extracted, while ownership and equity are denied.

The disparity is especially stark when one examines capital circulation. A dollar in the Black community circulates for less than 6 hours, according to HBCU Money, while in Jewish and Asian communities, it circulates for 17 and 20 days respectively. The consequence is an economy that is constantly depleted, reliant on external institutions for everything from finance to food. Hip-hop, despite its earnings, has not altered this trajectory. The Bugatti may be new, but the bank that financed it is old—and white.

This failure to institutionalize wealth is not accidental. It reflects deeper structural barriers, including a lack of access to financial infrastructure, intergenerational capital, and legal expertise. But it also reflects a shift in priorities within the culture itself. The era of Public Enemy and X-Clan once channeled music toward collective uplift. The current era often measures success by proximity to luxury, not impact on community. The metrics of power have changed from organization to ostentation.

Still, there are exceptions that point to what is possible. But these efforts remain underfunded and under-celebrated. There is no coordinated movement among hip-hop elites to pool capital, fund cooperative ventures, or launch institutional vehicles capable of rivaling their white counterparts. What could a $1 billion hip-hop endowment fund do for HBCUs? For land ownership? For venture funding of African American startups? These questions are never asked because the Bugatti is louder than the balance sheet.

It’s not just about what rappers buy. It’s about what they build or more accurately, what they have not built. For every luxury watch, there could be a community-owned grocery store. For every $30 million home, there could be a regional loan fund or student scholarship pipeline. The failure to institutionalize success means that when an artist dies, their wealth often dies with them dispersed among heirs or recaptured by the state or private corporations. There is no hip-hop university. No national Black credit union seeded by artists. No sovereign wealth fund of the culture.

Arnold Glasow’s warning—“If you think you’re tops, you won’t do much climbing”—rings like an indictment. The culture believes it has arrived, but the destination is superficial. It has conquered billboards but not balance sheets. The climbing left to do is immense: building a generation of lawyers, financiers, real estate developers, and economists who can institutionalize the gains of cultural dominance. Without this, hip-hop’s economic contribution will remain symbolic, not structural. The world will continue to dance to the music, while Black America stays undercapitalized.

A Bugatti depreciates. Institutions compound. Until hip-hop’s economic power stops ending with the individual and starts building for the collective, the community will remain stuck in a loop of representation without accumulation. The corner coffee shop that became Starbucks is not owned by the block. And the music booming from its speakers will not change that. Not unless the wealth it generates is used to build not just to boast.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.