“Change will not come if we wait for some other person or some other time. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for. We are the change that we seek.” – Barack Obama

It almost seems like an absurd question to ask, but…

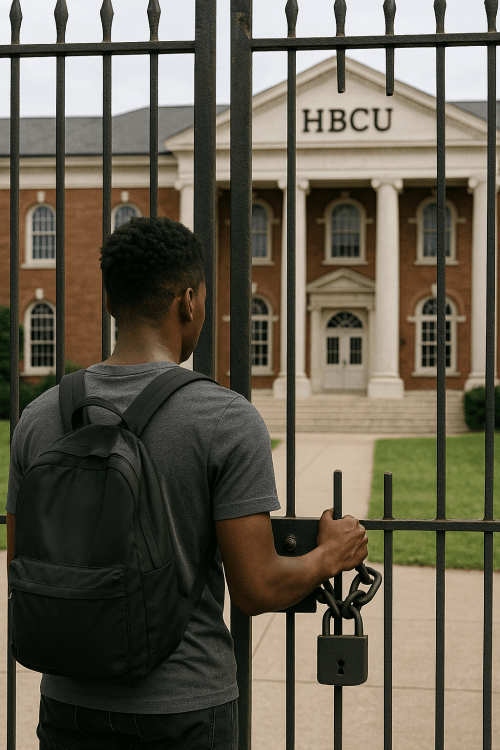

in 2025, the idea that Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) are no longer focused on recruiting African American students is not as far-fetched as it sounds. It’s a question whispered in alumni boardrooms, discussed in quiet conversations among concerned parents, and pondered in the minds of young Black students as they decide where to apply. While HBCUs remain vital institutions for the Black community, the numbers and decisions behind closed doors suggest that a shift is underway—one that demands scrutiny, reflection, and action.

In the decades since desegregation opened the doors of Predominantly White Institutions (PWIs) to Black students, the role and mission of HBCUs have been evolving. According to data from the Pew Research Center, Black student enrollment at HBCUs increased by just 15% from 1976 to 2022. Meanwhile, enrollment of students from other racial and ethnic groups rose by a staggering 117% during the same period. In 1976, Black students made up 85% of HBCU enrollment. By 2022, that number had dropped to 76%. That means nearly one in four HBCU students today is not Black. At at least five HBCUs, such as Bluefield State University, Lincoln University (MO), and West Virginia State University, White students now comprise the majority. While some view this as a testament to progress and inclusion, others see it as a troubling signal that the core mission of HBCUs, educating and empowering African American students, their families, and ultimately the social, economic, and political interest of African America, may be slipping.

Nowhere is this shift more alarming than in the enrollment of Black male students. In 1976, Black men made up 38% of students at HBCUs. By 2022, that number had fallen to just 26%. The decline is not only concerning it is an existential threat to the cultural and academic ecosystem of HBCUs, which once produced the very architects of Black political, business, and religious life. Many HBCUs now boast majority-female student bodies, a testament to the resilience and commitment of Black girls, but also a glaring reflection of systemic failure to support Black boys in education from kindergarten through college. The disappearance of Black young men from HBCU campuses must be seen for what it is: a crisis.

Some of the explanations are economic. Many HBCUs struggle with limited financial resources. According to HBCU Money’s 2024 endowment rankings, only one HBCU, Howard University, has an endowment exceeding $1 billion. Most HBCUs operate with endowments below $100 million, leaving them vulnerable to financial pressures that force them to make difficult choices. In that context, expanding recruitment to non-Black students may seem like a pragmatic strategy to increase tuition revenue, especially when those students are attracted by athletic scholarships in sports like soccer, baseball, and tennis—sports where African American participation is historically underrepresented. But when HBCUs prioritize this kind of recruitment while failing to maintain deep engagement with the Black communities that birthed them, they risk trading mission for margin.

The situation has also been shaped by the recruitment arms race. PWIs now actively recruit top Black students with full-ride scholarships, aggressive outreach, and promises of diversity and inclusion. For many Black high schoolers, a name-brand PWI with a large endowment and impressive campus facilities appears more appealing and more financially accessible than an underfunded HBCU. This has contributed to an image crisis for many HBCUs. Once the first choice for Black excellence, some HBCUs are increasingly viewed as a second-tier option, even among Black students themselves. This perception isn’t entirely fair, but it’s not without basis. Fewer in-person recruitment visits, fewer marketing campaigns that center Black identity, and an overreliance on digital outreach have all contributed to HBCUs becoming less visible in the spaces that matter most.

And yet, 2023 may have marked an inflection point. When the U.S. Supreme Court struck down race-conscious admissions at PWIs, many Black students and families began rethinking their college plans. In the aftermath of the ruling, applications to HBCUs surged. According to Inside Higher Ed, institutions such as Howard University, Florida A&M University, and North Carolina A&T reported double-digit increases in applications in 2024. These students, disillusioned by the erasure of diversity efforts at mainstream universities, began looking again to HBCUs as spaces where their identities were affirmed, not tolerated. This renewed interest is an opportunity, but also a test. Will HBCUs meet the moment?

To do so, recruitment must become intentional again not just broad-based or reactive. The recruitment of African American students, especially Black male students, needs to return to being a top institutional priority. That means more than sending emails or relying on the Common Black College Application. It means going into Black neighborhoods, hosting HBCU nights at community centers and churches, building relationships with high school counselors, and creating early K-8 pipeline programs. It means building community and cultural trust. The reality is, many Black high school students no longer have any personal connection to an HBCU. They may not know an alum. They may never have stepped on a campus. For HBCUs to thrive, they must reintroduce themselves.

And this is where alumni become vital. HBCU alumni are among the most loyal in the nation, but they are too often treated only as sources of homecoming participants. In truth, they are the best ambassadors. Empowering alumni to lead recruitment efforts, fund scholarships, and bring HBCU visibility to their local schools is an untapped strategy with enormous potential. HBCUs must support this with resources and coordination, not just hope.

The work also includes tackling affordability. More than 70% of HBCU students are Pell Grant eligible, compared to just 39% of students nationally. That means HBCUs disproportionately serve low-income, first-generation college students. For these students, even small gaps in aid can become barriers. Innovations like the reduced tuition and work-study model at Paul Quinn College show that reimagining cost structures is possible. Institutions that find ways to lower costs, provide housing and food support, and prioritize need-based aid will be the ones that retain and graduate more Black students.

At a deeper level, this conversation is not just about numbers. It’s about identity. The cultural mission of HBCUs cannot be outsourced. HBCUs are sacred institutions, repositories of Black intellectualism, resistance, and imagination. When they drift too far from that mission, they risk becoming something entirely different. Diversity should be additive, not dilutive. To serve the world, HBCUs must first continue serving the people who built them.

This doesn’t mean rejecting change. It means anchoring change in purpose. HBCUs can welcome diversity without losing their soul. But to do so, they must recommit to the hard, intentional work of finding and lifting up Black students not just those with 4.0 GPAs and high SAT scores, but also the creative thinkers, the late bloomers, the future leaders hiding in overlooked ZIP codes. These students may not be polished when they arrive, but neither were the trailblazers who founded these institutions. We owe them the same belief.

In the end, the question “Have HBCUs given up on recruiting African American students?” is not an accusation it is a call. A call to reignite the radical vision that gave birth to these schools in the first place. A call to remember that every Black student recruited to an HBCU is a declaration of faith in Black futures. A call to stop letting budget constraints dictate who gets to belong in spaces we built. And a call to Black America to advocate, to donate, to volunteer, and to remind our youth that these institutions are not relics of the past. They are sanctuaries for tomorrow. A fort of many that protects the social, economic, and political interest of African America.

In the words of Zora Neale Hurston, “There are years that ask questions and years that answer.” This year, the question has been asked. What comes next is up to all of us.

Sidebar Feature: Black Male Enrollment Crisis

- In 2022, only 26% of HBCU students were Black men.

- Compare that to 38% in 1976.

- Solutions include mentorship pipelines, mental health support, re-entry programs for formerly incarcerated youth, and dedicated Black male scholarships.

HBCU Money Action Items: How You Can Help (K-8 Focused)

1. The HBCU Express: Mobile Campus Experience

Transform a retired school bus into a rolling HBCU ambassador painted in your school’s colors, filled with college memorabilia, yearbooks, and screens showing campus life. Drive it to elementary schools during lunch or after school, let kids climb aboard, sit in “college seats,” and take photos. Make it an event kids talk about for weeks.

Bonus: Offer free rides to campus tours for families.

2. Saturday HBCU Youth Academies (On-Campus or Virtual)

Host monthly Saturday programs where K-8 students take classes taught by alumni and current students—coding, dance, robotics, creative writing, step team, debate. For chapters near campus, hold sessions in campus facilities with meals in the dining hall. For distant chapters (like a New York chapter for a Virginia HBCU), run virtual sessions where kids still see campus backgrounds, hear from current students, and feel connected to the institution. Hybrid models work too—virtual learning followed by an annual in-person campus visit.

3. HBCU Summer Day Camp Scholarships & Sponsorships

If the HBCU already runs summer day camps for ages 8-14, alumni chapters can fund full or partial scholarships so more K-8 students from underserved communities can attend for free. Chapters can also sponsor transportation (charter buses from their city to campus), provide camp supplies, fund field trips, or endow specific camp programs (STEM lab, arts workshop, sports clinic). For distant chapters, sponsor a group of local kids to travel to campus for the week-long experience—cover registration, travel, and meals. This removes financial barriers and gets more Black children on campus during formative years.

4. Adopt-a-School Family Weekends

Alumni chapters “adopt” local elementary or middle schools and sponsor quarterly weekend campus visits for groups of families with K-8 children. Time visits around campus events—football or basketball games, step shows, concert series, or even quiet weekends when students are just hanging out on the yard. Provide transportation, cover game tickets or event admission, and assign each family a paid student tour guide who walks them through dorms, the student center, dining halls, and academic buildings.

Let kids eat campus food, sit in lecture halls, and watch college students in their natural environment. Parents see the affordability, safety, and culture while kids fall in love with the energy. End with a family cookout or pizza party where alumni share their stories and parents ask real questions about financial aid, academics, and campus life. You’re selling the parents on the investment and indoctrinating the kids with belonging. Make it so memorable that families go home and tell everyone about “their weekend at the HBCU.”

5. HBCU Junior Homecoming

Create a “Little Yard Fest” during homecoming week specifically for K-8 students—kid-friendly step show performances, band practice visits, meet-and-greets with the mascot, face painting in school colors, and a mini parade. Let children experience the joy, pride, and cultural richness of HBCU homecoming. Give every child a “Future Class of 20XX” t-shirt. When homecoming becomes their childhood memory, attending becomes their teenage dream.

6. Community-Based Tutoring & Enrichment Centers

Alumni chapters establish free after-school and weekend tutoring programs in their local communities—at libraries, community centers, churches, or alumni members’ offices. Offer homework help, test prep, reading circles, and subject-specific support led by alumni volunteers. Decorate spaces with HBCU banners, pennants, and imagery. Kids get academic support while being surrounded by HBCU pride. Current college students can join virtually to provide tutoring, creating direct peer connections across distances.

7. HBCU Family Culture Days at Museums & Theaters

Partner with local museums, science centers, theaters, or cultural institutions to sponsor “HBCU Family Days” where alumni associations buy out tickets so parents and guardians can bring their K-8 children for free. Brand it visibly with school colors, have alumni volunteers greet families wearing HBCU gear, distribute information packets about the school, and create photo opportunities. Follow up with invitations to visit campus. It positions the HBCU as an institution invested in Black family enrichment and intellectual development.

8. Live Virtual Campus Walks & Class Sit-Ins

Alumni chapters coordinate with student organizations (SGA, fraternities, sororities, academic clubs) to host live virtual campus tours where current students walk K-8 children through campus via smartphone or camera—showing dorms, the yard, dining halls, the library, labs, and student hangout spots. Go beyond static tours: arrange for interested students to virtually “sit in” on actual college classes, club meetings, or rehearsals. Let them see what college life really looks like in real-time. Schedule Q&A sessions where kids can ask current students anything. This works for any chapter regardless of geographic distance and makes the campus feel accessible and alive.

The goal: Make HBCU campuses feel like second homes before kids even reach high school. When college decisions come, they won’t be choosing the unknown—they’ll be coming home.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT and ClaudeAI.