“To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships.” — W.E.B. Du Bois

Philanthropy, at its best, is not only about generosity but also about power. For African America and the broader African Diaspora, philanthropy has too often been reduced to the goodwill of outsider corporations, foundations, and billionaires whose dollars arrive with priorities and strings attached. If African American financial institutions are to play a central role in reshaping the destiny of our people, they must learn to wield the tools of modern philanthropy at scale. Chief among these tools is the donor-advised fund.

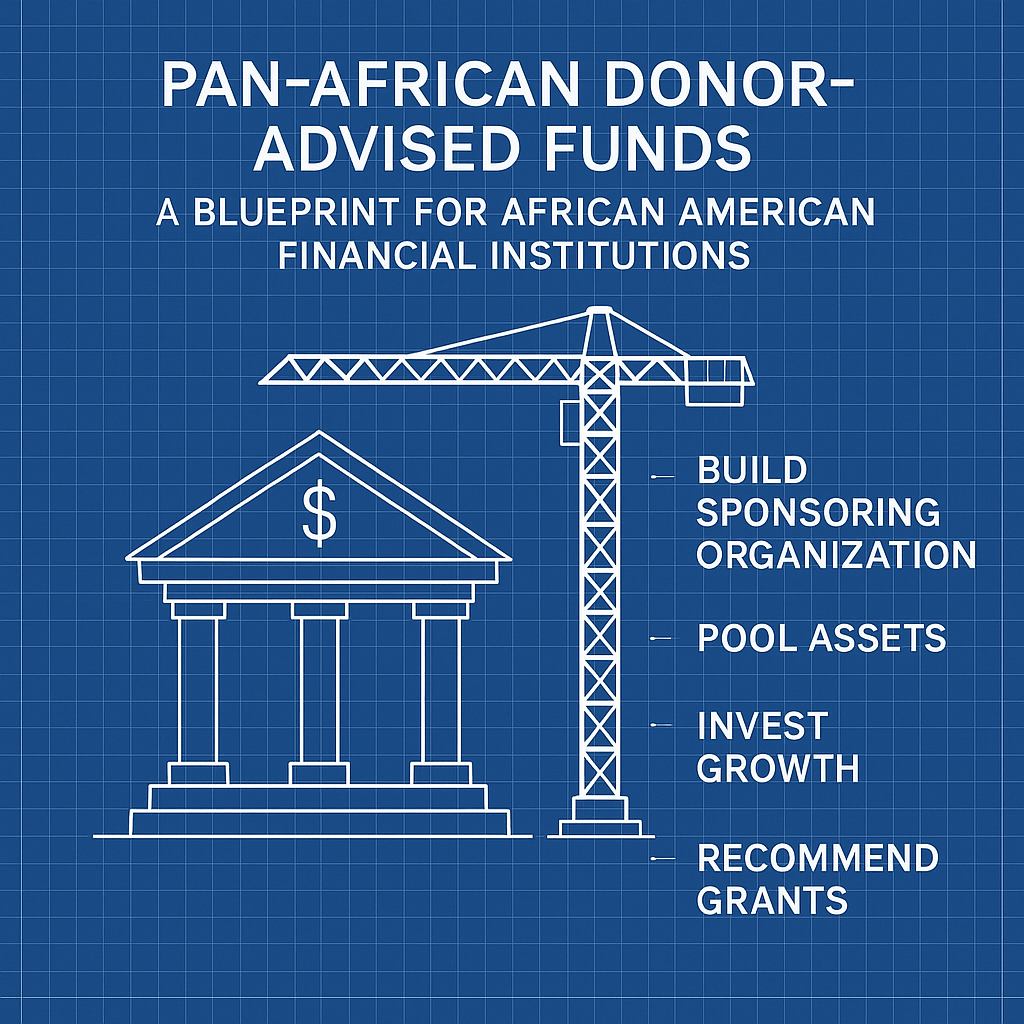

A donor-advised fund, or DAF, is a charitable giving vehicle hosted by a sponsoring public charity. Donors contribute assets such as cash, securities, or real estate, receive an immediate tax deduction, and then recommend grants to nonprofit organizations over time. These funds are often described as “charitable investment accounts,” because once assets are placed inside them they can be invested for tax-free growth, providing donors the flexibility to make grants years or even decades later. Unlike private foundations, DAFs do not carry heavy administrative costs, reporting requirements, or annual payout mandates. That combination of flexibility, efficiency, and tax benefit has made them the fastest-growing vehicle in philanthropy, with more than $229 billion in assets managed in the United States by 2022.

The technical mechanics are straightforward, but the implications for African American institutional power are profound. When majority institutions host DAFs, they not only manage the assets and collect the fees but also strengthen their institutional position in the broader philanthropic ecosystem. If African American banks, credit unions, and HBCUs were to host their own DAF platforms, they would retain both the capital and the influence. They would also ensure that those assets circulate internally, building the capacity of Black institutions rather than reinforcing external ones.

The Pan-African case for donor-advised funds grows out of both history and strategy. The African Diaspora is scattered across North America, the Caribbean, South America, Europe, and Africa. Despite cultural variations, there is a shared experience of enslavement, colonization, and systemic exclusion that has left us fragmented and underdeveloped institutionally. A Pan-African DAF would allow African America’s wealth to pool with Diasporic wealth, creating a philanthropic capital base that could fund initiatives from Harlem to Havana, from Lagos to London. Imagine a Spelman alumna in Atlanta, a banker in Kingston, and a tech entrepreneur in Nairobi all contributing to the same Pan-African DAF. The fund’s assets grow through coordinated investment, and the grants sustain HBCUs, African universities, Diaspora think tanks, hospitals, and cooperative businesses. Philanthropy would move beyond sporadic generosity into a coordinated, long-term Diasporic strategy.

African American financial institutions are uniquely positioned to lead in building these vehicles. Black-owned banks could create DAF platforms, allowing depositors and wealthier clients to establish accounts, with the bank managing the assets and directing grants into curated pools of African American and Diaspora institutions. HBCUs could build DAFs under their endowment arms, offering alumni the chance to contribute not just to individual schools but to collective vehicles that support Black higher education broadly. Credit unions, already rooted in cooperative traditions, could create member-based DAFs that channel contributions into scholarships, healthcare clinics, or Diaspora research projects. A Pan-African exchange could even emerge, allowing African American donors to support African institutions and African donors to support African American initiatives, breaking down silos and creating reciprocity.

The impact on philanthropy would be transformative. Pooling resources through Pan-African DAFs would reduce fragmentation and administrative waste. A single DAF with $1 billion in assets could deploy $50 million in annual grants while continuing to grow its capital base. Instead of thousands of scattered donations, these funds would strategically target long-term capacity-building institutions like universities, hospitals, and think tanks. They would also allow families to pass advisory privileges to children and grandchildren, embedding intergenerational philanthropy into family legacies. By linking U.S. tax benefits with Diaspora impact, Pan-African DAFs would connect global Black institutions across borders in ways never before achieved.

More than philanthropy, DAFs are about institutional power. Hosting our own funds would allow African America to retain capital that otherwise circulates through majority institutions. The act of managing billions in philanthropic assets would increase the legitimacy, visibility, and bargaining power of African American banks and credit unions in the national financial system. Control over DAFs also allows agenda-setting: funding HBCU graduate schools, African healthcare systems, Diaspora media, or land ownership initiatives. With sufficient scale, Pan-African DAFs would fund the think tanks, advocacy networks, and policy shops that shape legislation and strategy across the Diaspora. They would also strengthen interdependence between Black banks, universities, and cooperatives, weaving a tighter institutional ecosystem. And globally, they would reframe African American philanthropy as not merely domestic but as a force shaping development across Africa, the Caribbean, and beyond.

Mainstream philanthropic firms offer lessons. Fidelity Charitable, Schwab Charitable, and Vanguard Charitable collectively manage tens of billions in DAF assets, attracting donors with ease of use, professional management, and trusted brands. But they also embody the critique that DAFs can warehouse wealth indefinitely, giving donors immediate tax deductions without ensuring timely disbursement to communities. A Pan-African DAF must avoid this trap by committing to clear disbursement expectations, perhaps requiring annual grantmaking of 7 to 10 percent of assets. It must also invest in building trust and branding. Fidelity and Schwab are household names; African American financial institutions must cultivate similar reputations for professionalism, security, and vision if they are to attract donors at scale.

The roadmap to implementation is straightforward. Institutions must establish DAFs under existing nonprofit or financial arms with full compliance to IRS rules. They must develop Pan-African investment strategies that allocate assets into African American-owned funds, African sovereign bonds, and Diasporic infrastructure projects. They need technology platforms that allow donors to open accounts, contribute assets, recommend grants, and track impact with ease. Partnerships with vetted institutions across the Diaspora are essential, ensuring that grants reach trusted universities, hospitals, and cooperatives. Above all, a compelling public narrative must frame participation in Pan-African DAFs as not just philanthropy but as an act of liberation and institution building. Families should be encouraged to use DAFs to teach the next generation about philanthropy and responsibility, embedding giving as a permanent part of Diasporic culture.

The vision for the future is clear. By 2045, African American banks could be managing $100 billion in Pan-African DAFs, with $7–10 billion flowing annually into HBCUs, African universities, hospitals, and think tanks. Fee revenues from managing these assets would sustain our financial institutions, while the grants would expand the capacity of Diasporic institutions. The Pan-African DAF could become one of the most powerful philanthropic vehicles in the world, rivaling Gates, Ford, and Rockefeller. But unlike those entities, it would not be rooted in charity; it would be rooted in sovereignty. It would represent a Diaspora using philanthropy to build freedom, not dependency.

Donor-advised funds are not new, but their potential for African American and Pan-African institutions has yet to be realized. For too long, our wealth has flowed outward, strengthening others’ institutions while leaving ours fragile. By developing Pan-African DAFs, African American banks, credit unions, and HBCUs can capture that wealth, grow it, and deploy it across the Diaspora to increase our power. This is not simply about philanthropy; it is about sovereignty, agenda-setting, and survival. The next century will not be decided by who receives charity but by who controls the institutions that give it.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT