“What good are our institutions or our programs if they are not meant for the survival and empowerment of our people? We must be more than job seekers, we must be fighters for the Diaspora. These tools we learn have to be for a greater purpose.” – William A. Foster, IV

In Kabwe, Zambia, a seven-year-old girl named Winfrida sits in a classroom where learning feels like trying to climb a mountain barefoot. Once the site of one of the world’s largest lead mines, Kabwe is now infamous as perhaps the most lead-polluted place on earth. The town’s legacy of extraction has left behind poisoned soil, contaminated water, and a generation of children robbed of potential. At the same time, in Wilberforce, Ohio, a historically Black institution has been quietly developing an expertise that could one day prove critical to Kabwe’s recovery. Central State University, the nation’s only HBCU with a dedicated Water Resources Management program, is uniquely positioned to contribute to addressing this environmental catastrophe. The program’s interdisciplinary curriculum, rooted in both science and community engagement, is precisely the kind of training and research engine needed to tackle a challenge as complex as Kabwe’s. This moment offers a powerful illustration of how HBCUs too often overlooked in global problem-solving can step forward as leaders on the world stage. Central State’s water expertise is not only about classrooms and degrees. It could become an institutional bridge between African America and Africa, uniting technical skill with a shared historical experience of exploitation and resilience.

Kabwe’s crisis is the long shadow of a century of mining. The Broken Hill mine, opened in 1906 under British colonial rule, produced massive quantities of lead and zinc for global markets until it was shuttered in 1994. But its closure did not end the danger. Vast piles of lead-laden tailings remain exposed to the elements. Winds scatter toxic dust into homes, schools, and roads. During the rainy season, contaminated runoff seeps into rivers and groundwater. Decades later, blood-lead levels in Kabwe’s children remain among the highest recorded anywhere in the world. Symptoms range from learning disabilities and behavioral problems to stunted growth and organ damage. Entire generations risk being locked into cycles of poor health and diminished human capital. Remediation efforts have been fragmented. A World Bank-funded project cleaned some homes and public areas, but failed to address the core problem: the giant waste dumps that continue to spread contamination. Meanwhile, informal re-mining of tailings by small operators has created new pathways for lead exposure. Government plans for inter-ministerial action have stalled. The crisis persists.

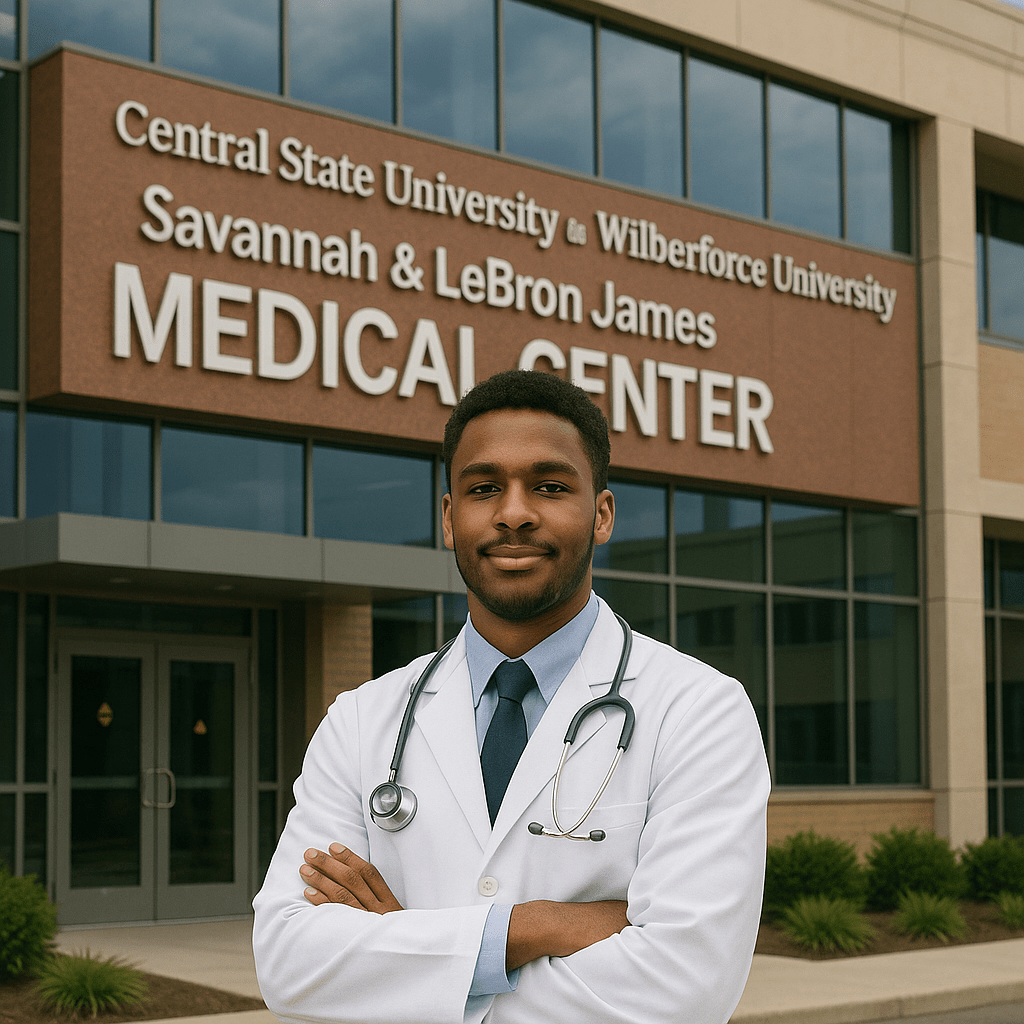

Central State’s Water Resources Management program, housed in the C.J. McLin International Center for Water Resources Management, stands as a rare jewel in American higher education. Launched in 1987, it remains the only HBCU-based program of its kind, and one of the few nationally that integrates the full spectrum of water and environmental challenges. The program offers both a B.S. degree and a minor, blending coursework in hydrology, environmental law, geology, pollution control, waste management, policy, and economics. Students learn not only how water flows through ecosystems but how laws, institutions, and communities interact with those systems. Its graduates have gone on to positions at the USDA, EPA, and Department of Defense, demonstrating its credibility in shaping professionals who can influence policy and practice. Under the leadership of Dr. Ramanitharan Kandiah, the department has expanded its reach and visibility. His recognition as a Diplomate of the American Water Resources Engineers and as a fellow of the ASCE Environmental & Water Resources Institute affirms the program’s high standing. His research portfolio supported by the NSF, USDA, DoD, and others ranges from groundwater quality and evapotranspiration modeling to water equity and resilience in the face of climate extremes. In short, Central State has the expertise to contribute meaningfully to environmental crises far beyond Ohio. The Kabwe disaster could be the kind of global challenge where an HBCU asserts its value not only to African America but to the African continent.

One of CSU’s greatest strengths is its grounding in interdisciplinary, community-engaged research. Kabwe’s crisis is not just about chemistry and soil samples it is about public health, poverty, governance, and trust. CSU students and faculty could partner with Zambian universities and NGOs to design research that combines hard science with social impact. They could map the spread of lead contamination through GIS and remote sensing, conduct water and soil testing to identify high-risk zones, and collaborate with public health teams to link contamination data to health outcomes in children. Kabwe also requires not only outside expertise but the development of local technical capacity. CSU could establish exchange programs that bring Zambian students and environmental professionals to Wilberforce for intensive training in water resources management, while sending CSU students and faculty to Zambia for fieldwork. Over time, this would build a corps of professionals embedded in Kabwe itself, capable of sustaining remediation and monitoring efforts.

The crisis is as much political as technical. Regulatory failure has allowed unsafe re-mining and inadequate cleanup to persist. CSU’s curriculum in environmental law and policy could help train Zambian regulators, civil servants, and community leaders. Workshops or certificate programs led jointly with Zambian institutions could help build governance capacity around environmental enforcement, licensing, and long-term remediation planning. Central State’s new Research and Demonstration Complex, opening in 2025 with advanced soil and water testing labs, could serve as a hub for innovation in remediation technologies. Pilot projects tested in Ohio could then be adapted to Zambia’s conditions. Techniques such as phytoremediation using plants to extract toxins from soil or low-cost water filtration systems could be developed and deployed. Because CSU is an HBCU, its involvement would carry symbolic weight. African American institutions engaging with African crises offers a model of diaspora solidarity. CSU could partner not only with Zambian universities but also with African American financial institutions, philanthropies, and think tanks to mobilize resources. This would expand the pool of actors beyond the typical World Bank or European NGO model.

The role of HBCUs in international development is rarely discussed. Yet they represent a set of institutions with technical expertise in fields like agriculture, health, and environmental science, a cultural and historical connection to Africa that mainstream U.S. universities lack, and community-based models of engagement rooted in serving marginalized populations. When Kabwe is framed purely as a “developing world” problem to be solved by Western aid agencies, the solutions often miss the nuances of community empowerment and self-determination. When an HBCU steps in, it reframes the issue: this is not charity, it is solidarity. It is institutions of African descent collaborating across the Atlantic to repair the legacies of extraction and neglect.

What might it look like in practice for Central State to become part of the solution in Kabwe? It could mean signing a memorandum of understanding with a Zambian partner university, such as the University of Zambia, focusing on water resources, public health, and environmental law. It could involve joint research grants targeting international funders to support Kabwe remediation studies. It could build a student exchange pipeline bringing Zambian students into CSU’s WRM program, funded by scholarships from African American philanthropic foundations. It could convene technical workshops in Kabwe led by CSU faculty, introducing low-cost soil testing and community monitoring methods. And it could establish an annual Diaspora Conference on Water and Environmental Justice, hosted alternately in Wilberforce and Zambia, convening experts, policymakers, and community activists. Such initiatives would institutionalize the partnership, ensuring it is not a one-off but a long-term bridge.

Of course, such an ambitious agenda faces challenges. CSU itself is a relatively small university with an endowment dwarfed by predominantly White institutions. International partnerships require funding, travel infrastructure, and political will. Zambia’s regulatory environment has historically been weak, and vested interests in re-mining waste piles may resist intervention. Yet these obstacles underscore the importance of approaching the issue institutionally rather than individually. For CSU to engage Kabwe meaningfully, it must do so as part of a larger HBCU and African American institutional ecosystem. This could mean drawing on African American-owned banks and credit unions to structure financing, HBCU consortia to pool faculty expertise, and diaspora philanthropic vehicles, like donor-advised funds, to direct giving toward global environmental justice.

Why should an HBCU in Ohio devote resources to a crisis in Zambia? Because doing so not only aids Kabwe but strengthens HBCUs themselves. By engaging globally, CSU elevates its reputation, attracts research funding, and demonstrates the relevance of HBCU scholarship in solving world problems. Students who participate in such projects gain transformative experiences that prepare them for leadership at home and abroad. Moreover, the symbolism matters. Just as the mine in Kabwe exported lead to the world, the environmental devastation it left behind is a global responsibility. HBCUs, born from a legacy of exclusion and survival, understand better than most what it means to inherit poisoned ground and still create knowledge and opportunity from it. Their engagement reframes Kabwe not as a distant tragedy, but as part of a shared struggle for dignity, health, and justice.

The children of Kabwe cannot wait. Each year of inaction locks in more damage to developing minds and bodies. The town’s soil and water remain a slow-moving disaster. Yet hope lies in partnerships that transcend borders. Central State University’s Water Resources program is not a silver bullet. But it embodies the kind of holistic, interdisciplinary, and justice-oriented approach that Kabwe desperately needs. An HBCU stepping into the breach would demonstrate that solutions to global crises can come not only from the usual centers of power, but from institutions born in the struggle of African America. In Wilberforce and Kabwe alike, the message would be clear: water is life, and the institutions of African people must be at the forefront of protecting it.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.