“I had crossed the line. I was free; but there was no one to welcome me to the land of freedom. I was a stranger in a strange land.” – Harriet Tubman

Race riots or rural reckoning? The answer lies beneath the surface—and often beneath the soil itself.

In the blistering summer of 1919, the United States erupted in racial violence unlike anything the country had witnessed since Reconstruction. From Washington, D.C. to Chicago, from Norfolk to Omaha, from Knoxville to the cotton fields of Arkansas, more than three dozen cities and rural towns became sites of bloodshed as white mobs attacked African American communities with a ferocity that was, in many instances, organized, deliberate, and unrelenting. Historians dubbed it the Red Summer, invoking both the color of blood and the communist anxieties of the era. For more than a century, the dominant explanation has centered on racial tensions stoked by the Great Migration, post-war competition for jobs, and white anxiety over African American assertiveness. But a deeper, more unsettling question lingers beneath those textbook explanations: was Red Summer not merely about urban unrest or racial animosity, but about land?

That question has returned with renewed urgency in recent years, amid a widening reexamination of Black land ownership and its deliberate erosion over the past century. As calls for reparations grow louder and more specific, so too does the need to reassess the forces that helped decimate Black wealth and autonomy in America. And when Red Summer is placed in that context, it begins to look less like a spontaneous explosion of racial rage and more like the bloodiest chapter in a longer, quieter war — a war fought not only over race but over soil.

The idea that African Americans were only victims of economic exclusion in early 20th-century America is a distortion that history has been slow to correct. By 1910, African Americans owned more than 15 million acres of land, largely concentrated in the South. Black farmers — most of them formerly enslaved or their direct descendants — had managed to accumulate land against crushing odds, frequently purchasing it collectively, through church cooperatives, fraternal organizations, or from white landowners seeking to offload marginal plots. These holdings were not merely symbolic achievements. They were strategic infrastructure.

Land ownership among Black Americans was more than a pathway to individual wealth; it was a bulwark against white supremacy. Land meant food security, political leverage, and a degree of independence in a nation otherwise constructed around Black dependency and racial domination. In some areas of the South, land ownership translated into Black-majority townships and counties, Black-controlled local economies, and the fragile but real possibility of a parallel civic sovereignty. Black landowners could vote with greater difficulty for whites to suppress. They could withhold labor. They could resist eviction. They could educate their children. They were, in a word, ungovernable in ways that landless sharecroppers were not.

African Americans were not simply asking for equality; in some places, they were building it. And that may have been the greatest threat of all.

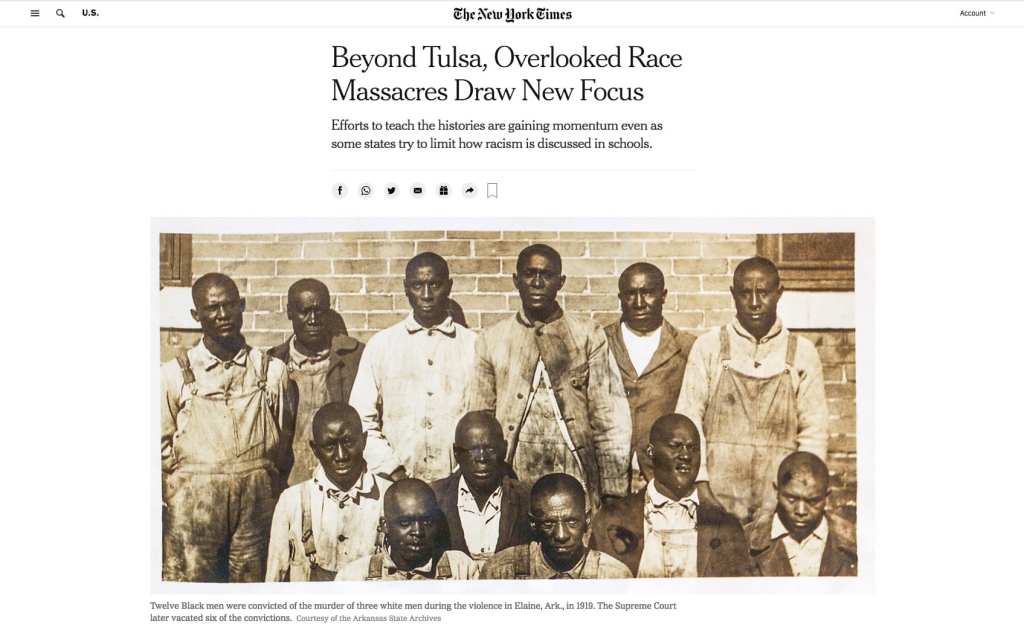

Nowhere is the link between land and lethal violence more clearly illustrated than in the massacre at Elaine, Arkansas — one of the deadliest and least discussed events of the entire Red Summer. On the night of September 30, 1919, African American sharecroppers gathered in a church in Phillips County to organize a union, the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America. Their goals were modest by any democratic standard: they wanted transparent accounting from the plantation owners who controlled the cotton market, an end to the rigged ledger systems that kept sharecroppers in perpetual debt, and the ability to sell their crops independently on the open market. It was a meeting about fair contracts, not rebellion. What descended upon them was a massacre.

White mobs, augmented by federal troops dispatched from Little Rock, swept through the area for days. An estimated 100 to 200 Black men, women, and children were killed, though the official tallies — sanitized for public consumption — counted only a handful of white deaths and labeled the episode a Black insurrection. The real insurrection was economic. The plantation economy of the Delta had been built on the enforced ignorance and powerlessness of its Black labor force. If Black sharecroppers could collectively organize, access fair markets, and demand accurate accounting, some of them might eventually become landowners themselves. That possibility — not armed revolt — was what the white establishment could not tolerate.

The Elaine massacre exposed a hidden economic architecture underlying Southern racial terror. Violence was not just an expression of hatred; it was a tool of market control. When the ledger failed to keep Black workers in debt, the mob stepped in. When the law was too slow, the rifle arrived first.

Though most of the events of Red Summer are framed through an urban lens — riots in Chicago, Washington, and Knoxville dominating the historical imagination — the violence cannot be disentangled from broader efforts to contain and reverse Black economic advancement. Indeed, many of the African Americans who had migrated to Northern cities were themselves displaced farmers or sharecroppers whose rural land ownership efforts had been stymied, swindled, or literally burned to the ground. The Great Migration was not only a story of aspiration; it was also a story of flight.

In Chicago, where violence erupted in late July after a Black teenager named Eugene Williams drowned after being struck by stones thrown by white men when he accidentally drifted past an informal racial boundary in Lake Michigan, the precipitating incident masked deeper structural conflicts. African Americans had begun purchasing homes and moving into previously all-white neighborhoods. Black entrepreneurs were opening businesses. The color line in Chicago was not just social — it was economic, and it was being crossed. What followed Williams’s death was a week of brutal violence that left 38 people dead and more than 500 injured. The riot was sparked by a beach dispute, but what it expressed was white terror at the prospect of Black economic mobility in the urban North.

Property rights were at the center of the Chicago conflict in ways that have only grown clearer with time. Redlining would not be formalized by the federal government until the 1930s, but the ideology animating it — that Black habitation diminished property values, that Black ownership was a form of invasion — was already operating through mob violence in 1919. White homeowners’ associations, some of which had explicitly bombed Black homes in the years leading up to the riot, continued their campaigns of intimidation with renewed license after the summer’s bloodshed. The message was consistent whether it came from the Delta or the Midwest: African Americans had no rightful claim to the land, whether in field or neighborhood.

What made Red Summer different from previous episodes of racial terror, and what made it so culturally resonant, was that it came at a moment when African American self-determination was not just a dream but a demonstrable reality. The years surrounding World War I had seen an extraordinary flowering of Black institutional life: newspapers like the Chicago Defender and the NAACP’s Crisis magazine reached hundreds of thousands of readers; the Universal Negro Improvement Association under Marcus Garvey was drawing mass followings with its message of African sovereignty; and Black veterans returning from the battlefields of France, having fought for democracy abroad, were unwilling to accept its absence at home. Many of these veterans would become central figures in the armed resistance that communities mounted against white mobs in 1919. They met violence with violence, and the White establishment found the combination of Black assertiveness, Black organization, and Black land deeply alarming.

The economic threat extended well beyond individual plots of farmland. In Tulsa, Oklahoma — whose 1921 Greenwood massacre falls just outside the official boundaries of Red Summer but belongs to the same continuum of violence — an entire district of Black economic life was leveled. Greenwood, known as Black Wall Street, was home to hundreds of Black-owned businesses, banks, law offices, and hotels. It was the product of deliberate community investment and collective self-determination. When white mobs descended in May 1921, aided by the Tulsa Police Department and private aircraft that reportedly dropped incendiary materials on the district, they did not merely kill people. They destroyed an economic ecosystem that had taken a generation to build. The land was seized. The insurance claims were denied. The neighborhood was never fully restored.

The pattern repeated itself, with local variations, across decades. What Red Summer initiated, the legal and bureaucratic infrastructure of mid-20th century America codified. Heirs’ property laws — in which land passed down without a formal will became jointly owned by all descendants — rendered Black landholdings acutely vulnerable to partition sales. A developer or speculator who purchased a single heir’s fractional share could force the sale of the entire property, often at below-market prices, with no recourse for the remaining family members. These laws, ostensibly race-neutral, operated with devastating specificity against Black families whose distrust of white legal institutions, forged over generations of documented fraud and violence, led them to avoid formal probate processes.

The federal government was often a direct participant in dispossession. The United States Department of Agriculture systematically denied Black farmers access to loans and subsidies that were extended routinely to their white counterparts. From the New Deal agricultural programs of the 1930s through the farm credit crisis of the 1980s, Black farmers were excluded, underfunded, and allowed to fail at rates far exceeding their white peers. In 1999, the Pigford v. Glickman class action settlement acknowledged decades of discriminatory lending by the USDA and resulted in payouts to tens of thousands of Black farmers — but by then, most of the land was already gone.

Numbers are beyond staggering in their finality. African Americans owned approximately 15 to 19 million acres of land at the peak of Black land ownership around 1910. By 1997, that figure had collapsed to fewer than 2 million acres — a loss of nearly 90 percent over the course of a single century. The USDA itself acknowledged that this loss was not driven solely by economic forces. Discrimination, fraud, violence, and legal manipulation played decisive roles in transferring land from Black families to white institutions and individuals.

The state of Black land ownership in America today reflects the accumulated weight of that century of dispossession. African Americans currently own less than 1 percent of rural land in the United States, despite constituting approximately 14 percent of the national population. In the South, where Black land ownership once represented a genuine counter-economy, the erasure is especially pronounced. In Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia — states where Black farmers built substantial holdings after Emancipation — Black land ownership has been reduced to a thin remnant. Entire family lineages have been severed from the soil their ancestors purchased with freedom wages, war bonuses, and borrowed hope.

Consequences extend far beyond sentiment. Land is the primary vehicle through which intergenerational wealth is transferred in the United States. Home equity and real property account for the majority of household net worth for most American families. The racial wealth gap — the persistent, yawning disparity between Black and white household wealth, which current estimates place at a ratio of roughly 1 to 8 — cannot be understood without accounting for the systematic denial of land and property rights to African Americans. Every generation of a Black family that was driven from its land, or swindled out of it, or watched it seized through partition sale or eminent domain, is a generation that could not pass on the compounding advantages of ownership. The wealth gap is not an accident of markets. It is the arithmetic of dispossession.

Contemporary efforts to address this reality operate at the margins of what is needed. Organizations like the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, founded in 1967, have worked for decades to help Black farmers retain land through legal assistance and cooperative economics. The Land Loss Prevention Project in North Carolina has challenged fraudulent partition sales and helped heirs navigate probate processes designed for a legal culture that was never built with them in mind. The Black Farmers Fund and similar initiatives provide capital and technical assistance to a dwindling population of Black agriculturalists. In 2021, Congress included provisions in the American Rescue Plan Act to provide debt relief to socially disadvantaged farmers — provisions that were subsequently challenged in federal court by white farmers who argued that race-conscious relief violated the Equal Protection Clause, a stunning inversion of the history that made such relief necessary.ve increasingly focused on this disparity. But to properly assess the scale of restitution, history must be rewritten to acknowledge not just the loss of life, but the loss of land. If Red Summer is reframed as a land war not only a race war, then it demands a different response.

Programs such as the Black Farmers Fund, the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, and the work of legal nonprofits like the Land Loss Prevention Project have begun to claw back some ground. Yet without a federal reckoning one that links racial violence to economic theft the narrative remains incomplete.

Reparations proposals have increasingly focused on land as the foundational unit of redress. Scholars like Thomas Mitchell, who pioneered the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act — now adopted in more than a dozen states — have worked to close the legal loopholes that enabled generations of Black land theft. Others have proposed direct federal land grants or land trusts as a more durable form of repair than cash payments alone. The argument is both pragmatic and historical: if land was what was taken, land is what must be restored.

But to make that argument with the force it deserves requires an honest reckoning with Red Summer as something more than a riot. It requires understanding 1919 not as an aberration but as an acceleration — the moment when informal systems of racial violence were enlisted on a national scale to reverse Black economic progress. The targets were not random. They were selected. Churches where sharecroppers organized were burned. Prosperous Black neighborhoods were razed. Landowners were murdered and their deeds contested in their absence. The land did not transfer by accident. It was taken by design, and the taking was protected, in county courthouses and federal offices alike, for decades afterward.

Malcolm X once observed that land is the basis of all independence. He was not speaking metaphorically. He was speaking from a tradition of Black political thought that understood, from Reconstruction onward, that the promises of American citizenship were hollow without the material foundation that land provides. The freedpeople who demanded forty acres understood this. The sharecroppers of Elaine who organized for fair prices understood it. The Greenwood entrepreneurs who built Black Wall Street understood it. And the white mobs, the plantation owners, the local sheriffs, the federal troops, and the discriminatory bureaucracies that systematically dismantled what Black Americans built — they understood it too.

Red Summer was not simply a spasm of postwar bigotry, nor an understandable if deplorable expression of racial anxiety. It was a calculated and coordinated assertion of dominance over a people who were, against every structural obstacle, building something that looked like sovereignty. The violence of 1919 did not emerge from nowhere, and it did not end with the cooling of summer temperatures. It opened a door that the legal and economic machinery of the 20th century walked through for decades, quietly completing the dispossession that the mobs had begun.

In the end, Red Summer may be remembered not only for its flames but for the fertile ground those flames sought permanently to char. It was not only a summer of blood. It was a war over soil — and the aftershocks of that war continue to shape the contours of American inequality today, in the wealth gaps, the landlessness, the severed inheritances, and the unanswered demands for repair that echo across every serious conversation about racial justice in this country.

📅 Visual Timeline: The Red Summer of 1919

April 13, 1919 – Jenkins County, Georgia

A violent confrontation erupts in Millen, Georgia, resulting in the deaths of six individuals and the destruction of African American churches and lodges.

May 10, 1919 – Charleston, South Carolina

White sailors initiate a riot, leading to the deaths of three African Americans and injuries to numerous others. Martial law is declared in response.

July 19–24, 1919 – Washington, D.C.

Racial violence breaks out as white mobs attack Black neighborhoods. African American residents organize self-defense efforts.

July 27–August 3, 1919 – Chicago, Illinois

The Chicago Race Riot begins after a Black teenager is killed for swimming in a “whites-only” area. The violence results in 38 deaths and over 500 injuries.

September 30–October 1, 1919 – Elaine, Arkansas

African American sharecroppers meeting to discuss fair compensation are attacked, leading to a massacre where estimates of Black fatalities range from 100 to 800.

October 4, 1919 – Gary, Indiana

Racial tensions escalate amid a steel strike, resulting in clashes between Black and white workers.

November 2, 1919 – Macon, Georgia

A Black man is lynched, highlighting the ongoing racial terror during this period.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ClaudeAI.