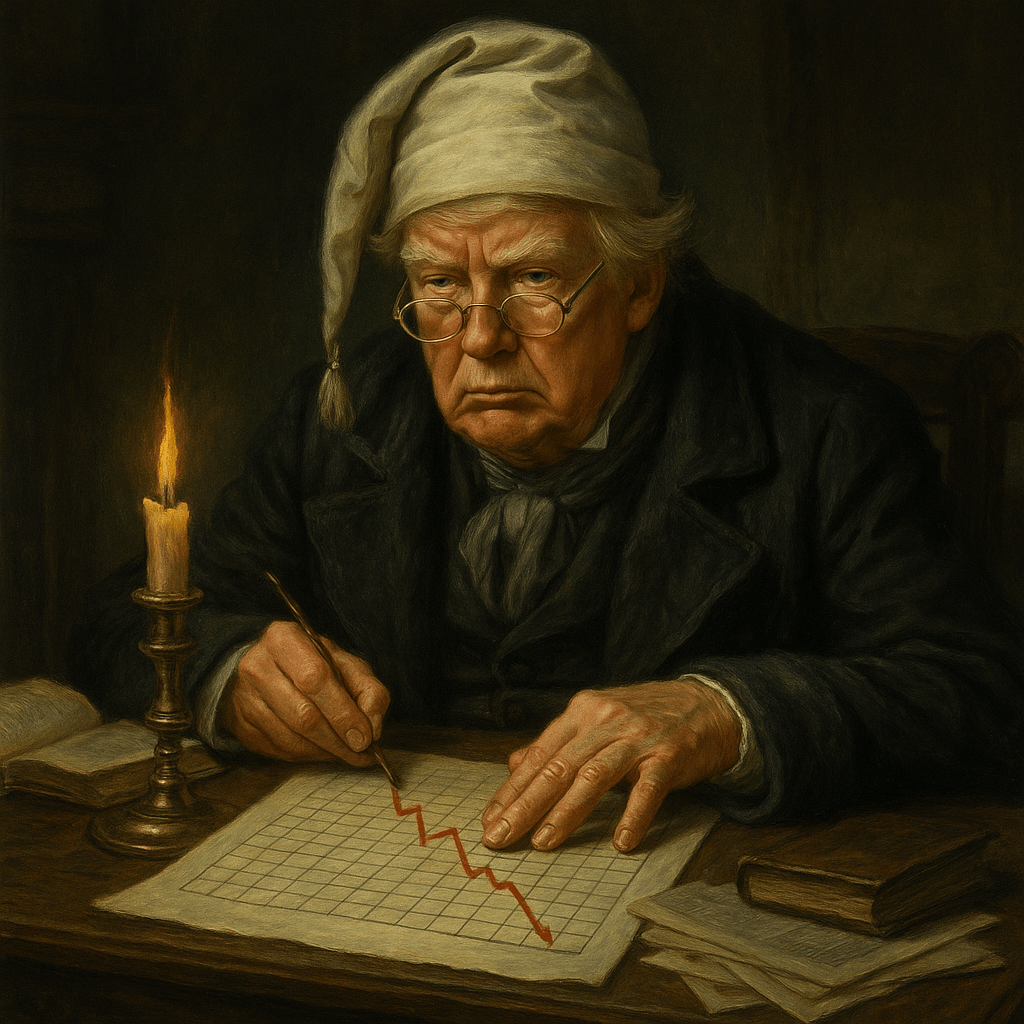

“When power makes truth expendable, only the brave will keep records.” — HBCU Money Editorial Board

On August 1, 2025, the United States crossed a threshold most democracies fear but few anticipate with precision the moment a nation’s statistical agency becomes a political target not for corruption, but for accuracy.

Following a weaker-than-expected jobs report with just 73,000 jobs added in July and significant downward revisions to prior months, President Donald Trump abruptly ordered the firing of Dr. Erika McEntarfer, Commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The justification? The data embarrassed him. The evidence? None. The implications? Profound.

For over a century, the BLS has served as the impartial scorekeeper of the American labor market. Its reports help inform everything from Federal Reserve monetary policy to wage negotiations, business expansion decisions, and university research. Most critically, the BLS is the foundation for public trust in employment data, a cornerstone of economic legitimacy.

Trump’s dismissal of Dr. McEntarfer, who was confirmed with bipartisan support and is regarded as a rigorous labor economist, did not challenge methodology, nor did it cite misconduct. Instead, it was an overt signal: when facts contradict the leader’s narrative, the facts must go.

This act is not merely executive overreach. It is an institutional decapitation. And it represents the clearest break yet from the post-WWII consensus that government data should be nonpartisan, methodologically sound, and politically untouchable. In a global economy, this is the equivalent of a currency devaluation not of the dollar, but of America’s data credibility.

When leadership no longer trusts or permits accurate data, policy becomes reactive, erratic, and performative. Investors, entrepreneurs, and institutions rely on the BLS to signal economic direction. Without it, credit markets misfire, fiscal policy lacks direction, and monetary policy becomes unmoored. For African American-owned banks, real estate firms, and HBCU endowment managers, this degrades their ability to assess employment trends in Black communities, apply for federal workforce grants, or time bond offerings based on unemployment benchmarks. Even philanthropic giving strategies may suffer if the poverty, wage, and employment data they are based on becomes manipulated or suppressed.

America’s strength lies in its institutions, not its individuals. By removing the head of a critical statistical agency on political grounds, the White House has signaled that no institution is beyond coercion. This undermines the rule of law and places civil servants especially those in technocratic roles on notice: loyalty matters more than evidence. African American civil servants, many of whom have worked tirelessly to diversify and reform these institutions from within, may see decades of credibility erased. It’s a chilling reminder that representation within agencies means little if those agencies are subject to autocratic whim.

International investors, trade partners, and credit agencies track U.S. labor data as a proxy for global economic health. If they begin to suspect that U.S. statistics are manipulated, they may hedge their investments, slow trade, or reevaluate the reliability of U.S. fiscal metrics. In the long-term, this can impact foreign direct investment in African American economic zones, HBCU research partnerships with global firms, and even diaspora remittance flows, if currency stability is affected by market anxiety.

Perhaps most dangerously, Trump’s decision follows a long trajectory of undermining truth-based systems elections, public health, the judiciary, and now economic data. This creates a vacuum in which conspiracy becomes conventional wisdom. In such an environment, fake facts become state currency. This has severe implications for African American institutions. Much of African American advocacy whether for reparations, investment, or educational equity rests on data. If national data sources are neutered or politicized, then the burden of proof shifts unfairly onto communities already under-resourced in research infrastructure.

HBCUs, Black think tanks, and African American foundations must view this firing not as a political blip, but a doctrine in action. When truth becomes negotiable, institutions that depend on it must move from passive reliance to active defense. HBCUs with strong economics, political science, or data science departments such as Howard, Spelman, and FAMU should develop Black-centered labor and socioeconomic data initiatives. These should complement, verify, or challenge federal data when necessary.

Institutions should also create safeguards digital, legal, and procedural to document how and when data manipulation may be occurring. This includes archiving historic BLS data, creating public dashboards, and writing explanatory briefs for the community. In addition, the next generation of data scientists, economists, and statisticians trained at HBCUs must be equipped not only with technical skill but a political consciousness of how truth is weaponized. Their work should be rooted not just in method, but in mission.

There is also an urgent need for civic engagement. African American policy organizations must pressure Congress to enact legal protections that insulate agencies like BLS, Census, and the Congressional Budget Office from political interference. Civil society must create watchdog coalitions that expose attempts to politicize data or intimidate public servants. Parallel to this, an emergency data defense fund backed by foundations and Black philanthropic leaders could help institutions respond rapidly to threats against data integrity.

Dr. McEntarfer’s firing is not merely about jobs data. It is about whether America will continue to govern itself by fact or by fiat. For African Americans, who have fought centuries of data invisibility, distortion, and misuse from redlining to police profiling the stakes are especially high.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics was once seen as above politics. That era is over.

African American institutions must now assume a new role not just consumers of data, but defenders of its integrity. If truth is to survive, it will not be because it was protected by tradition, but because it was guarded by those with the most to lose from its disappearance.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT.