The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. Intelligence plus character — that is the goal of true education. — Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., civil rights leader.

In the heart of Black America, Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) have long stood as bastions of culture, scholarship, and legacy. For over a century, they have been the educators of Black doctors, lawyers, artists, and entrepreneurs producing alumni who carry the spirit of service, resilience, and community into the wider world. But as the demographics of their faculty, administrators, and staff begin to shift away from their original mission, a cultural crisis looms. HBCUs are in danger of just becoming a diet version of PWIs. They are in danger of becoming Others’ institutions and no longer higher education institutions that represent the interests of African America and the larger Diaspora.

Today, fewer African American professors walk HBCU halls. Fewer Black deans shape curriculum rooted in our lived experience. And fewer culturally attuned staff members guide students with the kind of ancestral understanding that once made HBCUs more than just institutions they were safe havens.

We are witnessing a troubling erosion of what might best be described as the Cultural IQ of HBCUs. And at the center of this storm is a vanishing pipeline of HBCU alumni becoming the very educators and institutional leaders these colleges desperately need.

The data tell a sobering story. While overall enrollment at many HBCUs is stable or growing, the number of African American faculty and administrators is not keeping pace. According to a 2023 report by the National Center for Education Statistics, less than 55% of full-time faculty at HBCUs are African American, a decline from decades prior. The leadership picture is even more stark: several prominent HBCUs have seen key leadership roles—presidents, provosts, department chairs—filled by individuals with little to no HBCU or African American cultural background.

This is not a conversation about exclusion. It’s a conversation about preservation. Cultural IQ, the lived experience, emotional intelligence, and intergenerational memory that African American faculty bring to campus is vital to the mission of HBCUs.

“Our institutions are continuing their academic strength but becoming culturally unrecognizable,” says William A. Foster, IV, an economist, financier, and HBCU alumnus. “What happens when the very people who carry the oral and spiritual history of our schools are no longer the ones teaching and leading?”

From Alumni to Architects: Building a Faculty Pipeline

One of the most promising ways to reverse this trend is to create a clear, intentional pipeline for HBCU alumni to return as faculty, staff, and administrators. Many graduates of HBCUs would jump at the opportunity to come back but financial, professional, and institutional roadblocks often get in the way.

This is where the HBCU Faculty Development Network (HBCU-FDN) comes in. Founded to support faculty at HBCUs through professional development, mentoring, and pedagogical innovation, the Network is uniquely positioned to become the heartbeat of a renewed talent pipeline. But it needs more support and visibility.

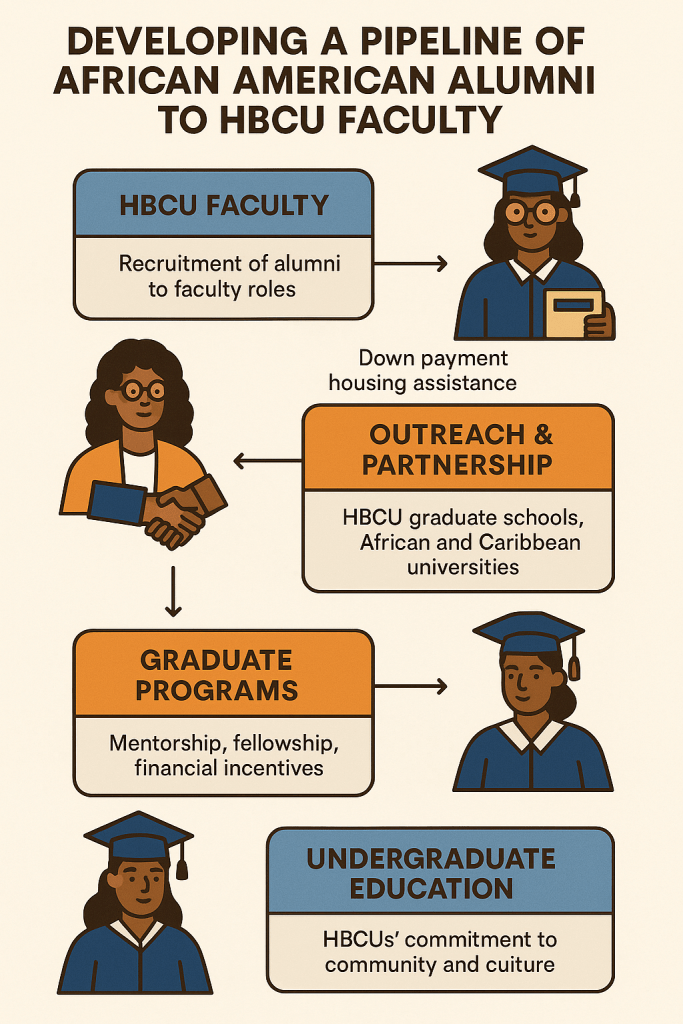

Imagine a structured, inter-HBCU program, one backed by governmental and philanthropic dollars that identifies promising undergraduates, supports them through HBCU graduate programs, places them in teaching assistantships, connects them to mentors through HBCU-FDN, and then guarantees interviews at HBCU campuses upon graduation. It’s time to rethink what faculty development means. We’re not just developing skills we’re preserving cultural continuity. HBCU graduate schools are uniquely situated to be the breeding ground for the next generation of African American faculty. From Howard’s School of Divinity to Florida A&M’s College of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, graduate students often come with a mix of cultural knowledge and scholarly ambition. But they need a system that encourages them to stay within the ecosystem.

Too often, HBCU graduate students are trained at their alma maters and then “exported” to majority-white institutions, both due to higher pay and limited on-campus faculty opportunities. A shift in strategy backed by deliberate investment could change this. Graduate assistantships that offer teaching experience, tuition remission, and research mentorships tied to HBCU-FDN could create a self-sustaining culture of scholarship. And importantly, HBCUs need to offer competitive packages to attract their own graduates back. There’s a deep emotional pull when you think about teaching where you were taught. But they have student loans to consider and cannot afford to come back just for nostalgia. This is where material incentives must meet mission.

Faculty retention is not just about recruitment it’s about creating lives worth living. For many HBCU alumni, particularly those returning to rural or economically challenged towns, the prospect of moving back to teach is made harder by financial instability. Housing support could be a game-changer.

Down payment assistance, low-interest home loans, and first-time buyer programs tied to faculty appointments would not only attract alumni but anchor them in the communities they serve. This model, successfully piloted in other sectors such as medicine and public education, could be expanded through HUD-HBCU partnerships, regional banks, or even campus-based community development funds.

“If you can give a medical school grad incentives to work in underserved areas, why not do the same for faculty at Black colleges?” argues Mr. Foster, who researches institutional economics and ecosystems. “The social return on investment is enormous.” Indeed, an HBCU that retains a culturally informed faculty member for 20 years gains more than a teacher, it gains a historian, a mentor, a surrogate parent, and a living curriculum.

Rebuilding the HBCU pipeline cannot be confined to American borders. HBCUs have a powerful opportunity to collaborate with African and Caribbean colleges and universities to build transnational faculty exchange programs, joint doctoral degrees, and even faculty credentialing pathways.

Imagine a Nigerian Ph.D. student at the University of Lagos who teaches for a semester at Tuskegee University as part of a diaspora exchange program. Or a Caribbean education scholar completing a visiting professorship at Southern University while collaborating on curriculum development. These aren’t flights of fancy they are strategic partnerships waiting to be forged.

The Pan-African intellectual tradition is our superpower. By partnering with African and Caribbean institutions, we infuse our campuses with a broader Black experience and build networks that empower all of us. Such partnerships could be coordinated through consortia like the Association of Caribbean Higher Education Administrators or the African Research Universities Alliance.

Cultural IQ is not just about familiarity with Black history. It’s about understanding how trauma, family structures, faith, language, resistance, and joy show up in the classroom. It’s about knowing why a student may resist authority or thrive under communal support. It’s about understanding the subtext behind silence or the significance of the Black church in a student’s worldview.

When HBCUs lose this kind of faculty wisdom, they risk becoming hollowed-out shells. Institutions may remain, but their souls quietly disappear. African American faculty are more likely to mentor Black students, use culturally relevant pedagogy, and engage in community-based scholarship. When that faculty is missing, students often feel less seen, less supported, and less likely to persist. In other words: retention of culturally attuned faculty improves student retention. To build this pipeline, bold philanthropy and supportive policy must go hand in hand.

Foundations like Mellon, Lumina, and the United Negro College Fund have already shown interest in faculty development. What’s needed now is alignment tying funding to long-term pipeline outcomes, incentivizing inter-HBCU faculty mobility, and supporting research programs that keep Black scholars engaged.

On the policy side, state legislatures and the federal government can expand Title III funding specifically for faculty recruitment and retention. The Department of Education could support teaching fellowships for HBCU alumni. And Congress could pilot a Faculty Forgiveness Program, where a portion of student loans is forgiven for each year of service at an HBCU. It is important to design anything in a politically strategic way that can survive political variances. This is about reparative investment. HBCUs gave so much with so little. The least we can do is fund the future of their faculties.

This isn’t just an institutional problem it’s a community imperative. If you’re an HBCU alum, consider returning to teach. If you’re a philanthropist, invest in the cultural stewards of our classrooms. If you’re a student, imagine yourself not just graduating but returning to guide the next class.

Reclaiming the Cultural IQ of HBCUs is not a luxury—it’s a necessity. Because no one can teach us like us.

Sidebar: What Is Cultural IQ?

Cultural IQ refers to the depth of understanding, sensitivity, and emotional intelligence that individuals bring to cultural experiences. At HBCUs, it’s the instinct to uplift, contextualize, and nurture Black students with care, rigor, and rooted knowledge. Faculty with high Cultural IQ don’t just teach Black students—they teach to them, for them, and with them.

Sidebar: The HBCU Faculty Development Network

HBCU-FDN is a nonprofit consortium of HBCUs dedicated to enhancing teaching effectiveness and professional development. The Network holds annual conferences, offers mentorship programs, and supports curriculum innovation across more than 100 institutions.

Learn more: https://hbcufdn.org

Callout Box: 5 Ways to Build the Faculty Pipeline Now

- Graduate Fellowships for HBCU alumni to pursue advanced degrees at HBCUs.

- Teaching Assistantships tied to faculty mentorship and career placement.

- Homeownership Incentives for faculty moving into HBCU communities.

- Faculty Exchange Programs with African and Caribbean institutions.

- Student Loan Forgiveness for multi-year faculty service at HBCUs.

- Sabbatical Programs for faculty to spend a year doing research.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ChatGPT