Debt is part of the human condition. Civilization is based on exchanges – on gifts, trades, loans – and the revenges and insults that come when they are not paid back. – Margaret Atwood

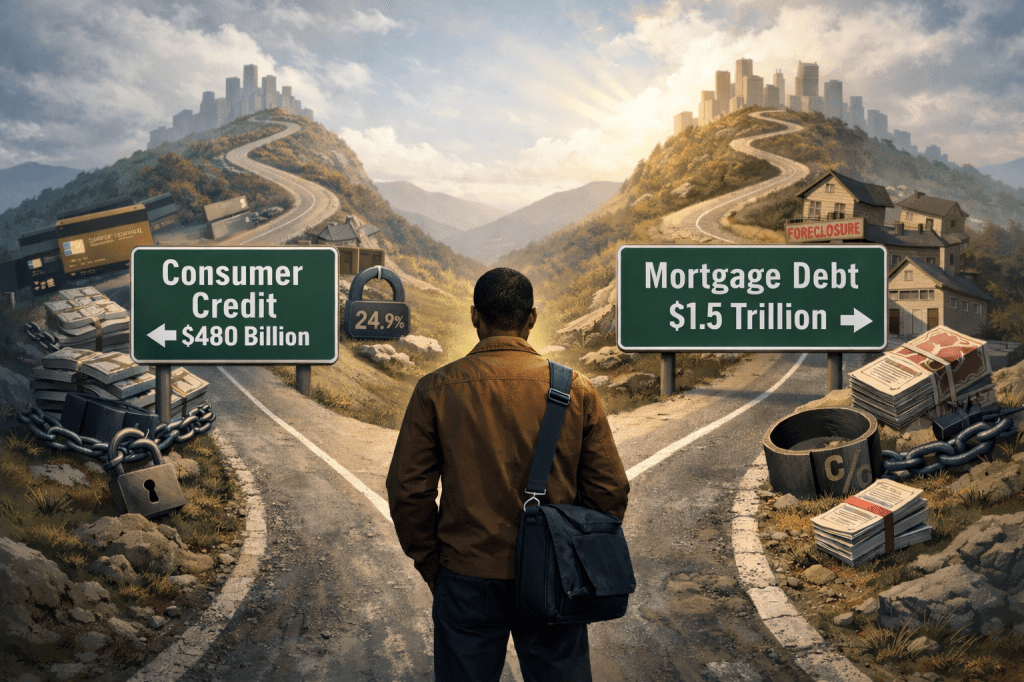

The mathematics of African American household debt present a stark choice: either eliminate $480 billion in consumer credit or add $1.5 trillion in mortgage debt. These are the pathways to achieving the 3:1 mortgage-to-consumer-credit ratio that European, Hispanic, and other American households maintain as a baseline of financial health. The first option requires African Americans to reduce consumer borrowing by 65% while maintaining current mortgage levels. The second demands increasing mortgage debt by 185% from $780 billion to $2.22 trillion while holding consumer credit constant. Neither path is realistic in isolation, yet both illuminate the extraordinary structural challenge facing Black households attempting to build wealth in an economy designed to extract it.

The current debt profile of $780 billion in mortgages against $740 billion in consumer credit represents an almost perfect inversion of healthy household finance. To understand the magnitude of correction required, consider what a 3:1 ratio would mean in practice. If African American households maintained their current $780 billion in mortgage debt, consumer credit would need to fall to $260 billion, a reduction of $480 billion. Alternatively, if consumer credit remained at $740 billion, mortgage debt would need to rise to $2.22 trillion, an increase of $1.44 trillion. The symmetry of these impossible requirements reveals how far African American household finance has diverged from sustainable wealth-building patterns.

The consumer credit reduction scenario appears superficially more achievable. After all, paying down debt requires discipline and sacrifice rather than access to new credit markets. Yet the practical barriers are immense. Consumer credit serves multiple functions in African American households, not all of them discretionary. Medical debt, a significant component of consumer credit, reflects the reality that Black Americans face higher rates of chronic illness while having lower rates of health insurance coverage and higher out-of-pocket costs. Transportation debt, often in the form of auto loans that blur the line between consumer and secured credit, reflects the necessity of vehicle ownership in a nation with limited public transit and residential patterns shaped by decades of housing discrimination that placed Black communities far from employment centers.

Even the portion of consumer credit that finances consumption rather than necessity spending reflects structural constraints. When median Black household income remains roughly 60% of median white household income, and when emergency savings remain inadequate due to lower wealth accumulation, consumer credit becomes a volatility buffer—a way to smooth consumption when irregular expenses arise. The Federal Reserve’s Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking consistently shows that Black households are significantly more likely than white households to report that they could not cover a $400 emergency expense without borrowing or selling something. This is not improvidence; it is the predictable result of income and wealth gaps that leave no margin for error.

Reducing consumer credit by $480 billion would require African American households to collectively pay down debt at a rate of approximately $40 billion per month for a year, or $3.3 billion per month for twelve years, assuming no new consumer debt accumulation. Given that African American households currently carry 15% of all U.S. consumer credit while representing 13% of the population, this would require Black households to dramatically outperform all other groups in debt reduction while maintaining living standards and weathering economic volatility without the credit cushion that has become structurally embedded in their financial lives.

The mortgage expansion scenario presents different but equally formidable challenges. Adding $1.44 trillion in mortgage debt would require African American homeownership to expand dramatically or existing homeowners to take on substantially larger mortgages. Current African American homeownership stands at approximately 45%, compared to 74% for white households. Yet even closing this gap entirely would be insufficient. To generate $1.44 trillion in new mortgage debt at the median Black home value of $242,600 (according to BlackDemographics.com analysis of Census data), African American homeownership would need to reach 87%—a rate no demographic group in American history has ever achieved. For context, white homeownership peaks at 74%, Asian American homeownership reaches approximately 63%, and Hispanic homeownership stands around 51%. The mortgage expansion path requires Black households to exceed the performance of every other demographic group by more than 13 percentage points while navigating credit markets that systematically disadvantage them.

More realistic would be existing homeowners trading up to more expensive properties or extracting equity through cash-out refinancing. Yet here too the barriers are substantial. The 2025 LendingTree analysis showing 19% denial rates for Black mortgage applicants reveals that even creditworthy Black borrowers face systematic disadvantages in accessing mortgage credit. For those who do gain approval, interest rate disparities mean that Black borrowers pay higher costs for the same debt, reducing the wealth-building potential of homeownership while increasing monthly payment burdens.

There is also the question of whether massive mortgage expansion would even be desirable. The 2008 financial crisis demonstrated the dangers of over-leveraging households on housing debt. While the crisis hit all communities, African American households suffered disproportionate wealth destruction, losing 53% of their wealth between 2005 and 2009 compared to 16% for white households. This reflected both predatory lending practices that steered Black borrowers toward subprime mortgages and the concentration of Black wealth in housing, which meant that home price declines destroyed a larger share of Black household balance sheets. Adding $1.44 trillion in mortgage debt without addressing underlying income inequality, employment instability, and institutional weakness would simply create a larger foundation upon which the next crisis could inflict even greater damage.

Nor would shifting the focus toward investment properties rather than primary residences solve this vulnerability. While rental properties offer income generation and different tax treatment, they would further concentrate African American wealth in real estate potentially pushing the share from the current 60% of assets concentrated in real estate and retirement accounts to 75% or higher in property holdings alone. When real estate markets crash, they crash comprehensively, taking both owner-occupied homes and rental properties down together. The 2008 crisis demonstrated this brutally: Black investors who had built portfolios of rental properties lost everything when tenants couldn’t pay rent during the recession, forcing investors to carry multiple mortgages they couldn’t service, leading to cascading foreclosures across their entire property holdings. Investment real estate offers no escape from concentration risk when households lack the liquid assets, diversified portfolios, and institutional support systems necessary to weather market downturns. With African American households holding just $330 billion in corporate equities and mutual funds—a mere 4.7% of their assets—there simply isn’t enough non-real-estate wealth to cushion the impact of property market volatility, regardless of whether the properties are owner-occupied or investment holdings.

The geographic dimension of mortgage expansion presents additional complications. African American homeownership is concentrated in markets where home values have historically appreciated more slowly than in majority-white submarkets. A recent Redfin analysis found that homes in majority-Black neighborhoods appreciated 45% less than homes in majority-white neighborhoods over a fifteen-year period, even after controlling for initial home values and location. This means that even substantial increases in mortgage debt may not generate proportional wealth accumulation if the underlying properties do not appreciate at competitive rates. The legacy of redlining, racial zoning, and exclusionary land use policies has created a geography of disadvantage where Black homeownership builds less wealth per dollar of debt than white homeownership.

The institutional barriers to either path are equally daunting. African American-owned banks hold just $6.4 billion in assets, while African American credit unions hold $8.2 billion. Together, these institutions control less than $15 billion in lending capacity. If these institutions were to facilitate a $480 billion reduction in consumer credit by offering debt consolidation loans at lower rates, they would need to increase their asset base by more than thirtyfold. If they were to finance a $1.44 trillion increase in mortgage debt, they would need to grow nearly hundredfold. Neither is feasible within any realistic timeframe, meaning that any significant shift in African American debt composition must flow through institutions owned by other communities, the same institutions whose discriminatory practices and wealth extraction mechanisms created the current imbalance.

There are no African American-owned credit card companies, no Black-controlled mortgage servicers of scale, no African American commercial banks with the balance sheet capacity to originate billions in mortgage debt. This institutional void means that even if African American households collectively decided to restructure their debt profiles, they would lack the institutional infrastructure to execute that restructuring on their own terms. Every loan refinanced, every new mortgage originated, every credit card balance transferred would enrich institutions outside the community, perpetuating the extraction cycle even as households attempted to escape it.

The policy environment offers little assistance. The Federal Housing Administration, which once provided a pathway to homeownership for millions of Americans, has become a more expensive option than conventional mortgages for many borrowers, with mortgage insurance premiums that never fall away. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-sponsored enterprises that dominate the mortgage market, have made reforms to reduce racial disparities in underwriting, but these changes have been modest and face political resistance. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau regulations that might limit predatory lending face uncertain enforcement in a political environment hostile to financial regulation.

State and local down payment assistance programs exist but remain underfunded relative to need. Employer-assisted housing programs, which some corporations have established to help employees become homeowners, rarely reach the Black workers who need them most, both because African Americans are underrepresented in the professional class jobs these programs typically target and because the programs often require employment tenure that Black workers, facing higher job instability, are less likely to achieve.

The theoretical third path—simultaneous reduction in consumer credit and expansion of mortgage debt—might seem to offer a middle ground. If African American households could reduce consumer credit by $240 billion while increasing mortgage debt by $720 billion, the 3:1 ratio could be achieved through a more balanced adjustment. Yet this scenario simply combines the barriers of both approaches: it requires access to mortgage credit that discrimination constrains, while also requiring debt paydown that income and wealth gaps make difficult, all while navigating through institutions that lack alignment with Black community interests.

What makes the entire framing particularly troubling is that it treats symptoms rather than causes. The 3:1 ratio that other communities achieve is not the result of superior financial planning or cultural advantage. It reflects higher incomes that reduce the need for consumer credit to smooth consumption, greater wealth that provides emergency buffers without borrowing, better access to mortgage credit at favorable terms, stronger financial institutions serving their communities, and residential patterns that allow homeownership to build wealth efficiently. African American households face the inverse of each advantage: lower incomes, less wealth, worse credit access, weaker institutions, and housing markets structured to extract rather than build wealth.

Pursuing a 3:1 ratio without addressing these structural factors would be like treating a fever without addressing the underlying infection. The ratio is a symptom of deeper pathologies: systematic wage discrimination that has suppressed Black income for generations, wealth destruction through urban renewal and highway construction that demolished Black business districts, redlining and racial covenants that prevented Black families from accessing appreciating housing markets during the great postwar suburban expansion, mass incarceration that removed millions of Black men from the labor force and branded millions more as essentially unemployable, and the steady erosion of the institutional infrastructure that might have provided some counterweight to these forces.

The data from HBCU Money’s 2024 African American Annual Wealth Report shows African American households with $7.1 trillion in assets and $1.55 trillion in liabilities, yielding approximately $5.6 trillion in net wealth. Yet this wealth is overwhelmingly concentrated in illiquid assets, real estate and retirement accounts comprising nearly 60% of holdings. The modest $330 billion in corporate equities and mutual fund shares represents just 0.7% of total U.S. household equity holdings. This concentration in illiquid assets means that even households with substantial paper wealth lack the liquidity to manage volatility without consumer credit, while also lacking the income-producing assets that might reduce dependence on labor income.

The comparison with other minority communities is instructive. According to the FDIC’s Minority Depository Institution program, Asian American banks control $174 billion in assets, Hispanic American banks hold $138 billion, while African American banks manage just $6.4 billion. These disparities reflect different histories of exclusion and different patterns of institutional development, but they also reveal possibilities. Hispanic and Asian American communities have managed to build and sustain financial institutions at scales that enable meaningful intermediation of community capital. African American communities have not, and the debt crisis is one manifestation of this institutional failure.

The question is not really whether African American households should reduce consumer credit by $480 billion or increase mortgage debt by $1.44 trillion. Neither is achievable through household-level decisions alone, and both would leave unchanged the extraction mechanisms and institutional weaknesses that created the crisis. The question is whether the structural conditions that make the current debt profile inevitable like income inequality, wealth gaps, discriminatory credit markets, institutional underdevelopment can be addressed at a scale and pace sufficient to prevent the debt trap from closing entirely.

The urgency is real. Consumer credit growing at 10.4% annually while mortgage debt grows at 4.0% and assets appreciate even more slowly suggests an accelerating divergence. Each year, the gap widens. Each year, the extraction intensifies. Each year, the institutional capacity to respond weakens as Black-owned banks close and credit unions remain trapped at subscale. The mathematics of debt restructuring, stark as they are, pale beside the mathematics of compounding disadvantage where each year’s extraction reduces the capacity to resist next year’s, creating a downward spiral from which escape becomes progressively more difficult.

The $480 billion or $1.5 trillion question is not really about debt reduction or mortgage expansion. It is about whether a community can restructure its household finances while lacking institutional control over the credit markets it must navigate, while facing discrimination at every point of access, while generating wealth that flows immediately out of the community through interest payments, fees, and rent extraction. The answer, based on current trajectories, appears to be no. The alternative is building the institutional infrastructure, addressing the income and wealth gaps, reforming the credit markets that requires a scale of intervention that African America’s current political and economic institutional conditions make unlikely. And so the debt trap closes, slowly but inexorably, converting nominal wealth gains into real wealth extraction, one interest payment at a time.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ClaudeAI.