“Our children can’t be what they can’t see.” — Marian Wright Edelman

In August 2015, HBCU Money asked a provocative question: What if LeBron James were a doctor? It was more than a hypothetical. It was a cultural critique of how African American communities disproportionately invest their most visible male potential into athletics rather than professions like medicine, law, or academia. The premise was simple: what if the best of us were guided toward healing rather than hoops?

At that time, Bronny James was only 10 years old. He was already receiving national media coverage and projected to follow in the footsteps of his famous father. Ten years later, we know how the story unfolded: Bronny James is now 20 years old, an NBA player for the Los Angeles Lakers, having been selected 55th overall in the 2024 NBA Draft. He and LeBron have made history as the NBA’s first active father–son duo. But as we revisit that original question, we offer a new one for this moment:

What if Bronny James were a doctor?

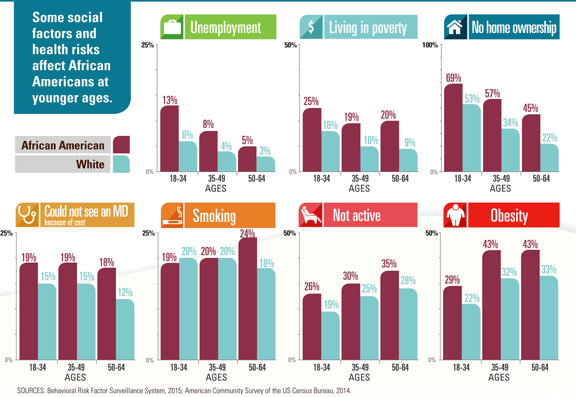

The Pipeline That Still Leaks

In the decade since the original article, the numbers have moved very little. Black men remain just 2.9% of medical school applicants in the United States. While the total percentage of Black physicians has risen slightly to 5.2%, Black male doctors remain critically underrepresented in the field. The pipeline is still broken—too narrow, too leaky, and too unprotected.

Meanwhile, sports pipelines are expanding. Black male participation in college athletics remains high: 44% in NCAA Division I basketball and 40% in football. Yet only a fraction make it to the pros, and even fewer achieve career longevity. While Bronny James may earn an estimated $33 million over five years in the NBA, that sum when spread over a lifetime equates to about $750,000 annually pro-rated from age 21 to 65. By contrast, a primary care physician earning $280,000 annually over a 35-year career will earn nearly $10 million, with the added benefits of job security, community impact, and longevity.

Imagining Dr. Bronny James

What if Bronny James had chosen to study medicine instead of basketball?

He would now be entering his second year of medical school, perhaps at Morehouse, Howard, or Meharry. He would be poring over medical textbooks, studying cardiovascular anatomy, shadowing trauma surgeons, and preparing for his USMLE Step 1 exam. Instead of prepping for NBA Summer League, he’d be interning at the Cleveland Clinic or doing a rural health rotation through an HBCU pipeline program.

Bronny would not trend on Twitter. He would not have endorsement deals. But one day, he would help save lives. He might build a medical clinic in Akron, establish scholarships for Black boys in pre-med tracks, or serve as a thought leader in health equity. His white coat would carry power every bit as influential as his jersey and perhaps more transformative.

Investing in the Wrong Dream?

The culture of African American investment in financial, emotional, and institutional remains lopsided. Parents spend thousands each year on club sports, trainers, uniforms, and travel tournaments. The AAU circuit is a multi-billion-dollar enterprise. But few parents are encouraged or supported to invest similarly in chess clubs, science fairs, or summer medical programs. The problem isn’t sports. The problem is singularity. We teach Black boys to put all their ambition into the least likely path to success. That is not empowerment it is misallocation.

Sports should be one of the dreams. Not the dream.

And cultural influencers like celebrities, churches, schools, and even HBCUs must widen the lens of what is considered aspirational. Because when African American boys only see themselves celebrated on the court or field, they are conditioned to believe that’s the only route to greatness.

The Hospital That Could Change Everything

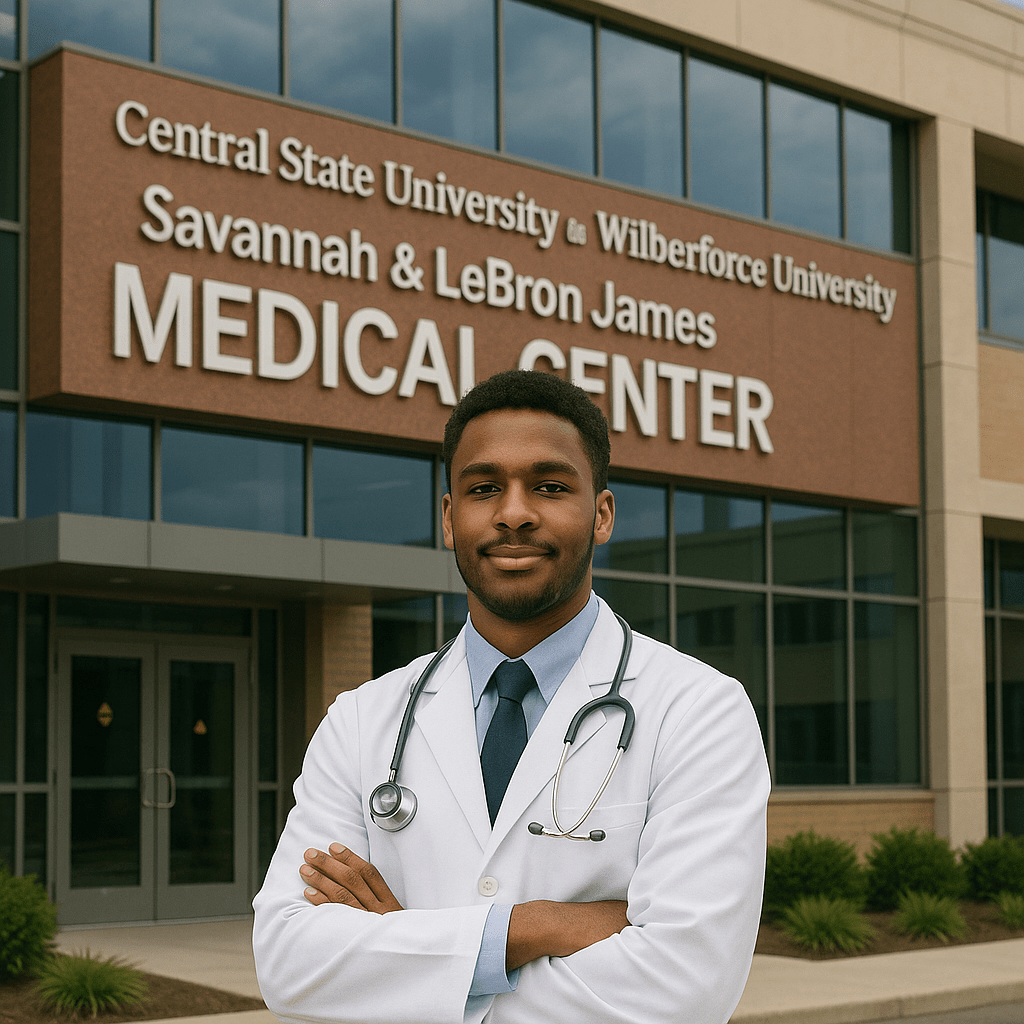

Now imagine a future where LeBron and Savannah James decide to reshape the health destiny of Black Ohio not just through education, but through medicine. In partnership with Central State University and Wilberforce University, the James family announces the creation of the Savannah & LeBron James Medical Center, a state-of-the-art teaching and research hospital in Dayton, Ohio. The hospital would be co-owned by the two HBCUs, offering an unprecedented model of HBCU institutional control and healthcare delivery.

At its helm? Dr. Bronny James, a board-certified trauma surgeon and hospital executive, returned from medical training with a mission not just to serve, but to system-build. Through a strategic pipeline, students from the I PROMISE School in Akron, established by the James family, would be funneled into dual-admissions programs at Wilberforce and Central State, beginning in middle school. African American students interested in health sciences would receive mentorship, MCAT preparation, research internships, and full scholarships in exchange for a five-year service commitment at the hospital.

The hospital would:

- Serve as a Level 1 trauma center for the Midwest Black Belt.

- Anchor a Black-owned HMO focused on preventive care and wellness.

- House medical research departments focused on sickle cell, hypertension, and diabetes, disproportionately affecting Black populations.

- Be staffed by a growing cadre of Black doctors, nurses, and technicians, trained from within the HBCU system.

It would be the first modern, Black-owned academic medical center in America in over a century.

Not just a facility but a movement.

HBCUs as Healthcare Engines

This is the next evolution for HBCUs. No longer content to only educate they must now employ, own, and lead. Currently, Meharry, Howard, and Morehouse are the most visible HBCU medical institutions, but they are not sufficient to serve a national population. HBCUs like Central State and Wilberforce can and should partner with philanthropists to enter the healthcare delivery space. Hospitals, urgent care clinics, dental schools, nursing programs—these are all industries HBCUs can lead, if given the capital and political will.

The Savannah & LeBron James Medical Center would become a model for how celebrity philanthropy can shift from access to ownership. The James family has built schools. Now they can build systems. Systems that outlast careers. Systems that create intergenerational empowerment. And Dr. Bronny James? He would not just be a doctor. He would be a symbol of new possibilities.

Culture, Media, and The Battle for Imagination

The Bronny we know exists because the culture invested in him—from trainers to scouts to sports media coverage. But imagine if that same investment were redirected into medicine.

What if:

- ESPN tracked the top Black high school biology students?

- SpringHill Company aired a documentary series on Black med students at HBCUs?

- Nike sponsored lab coats instead of just sneakers?

Culture tells children what to value. The question is whether we value Black intellect enough to mass-produce it.

Father–Son Legacy: A New Kind of First

LeBron and Bronny made history as the NBA’s first active father-son duo. But what if they made history again this time as a father-son pair who reshaped African American health care? Imagine LeBron standing beside Bronny at the ribbon-cutting of the James Medical Center. One created legacy through sport. The other, through healing. That is a legacy few families could rival. That is the kind of dynasty African America needs now.

Final Thoughts: From Possibility to Policy

“What if Bronny James were a doctor?” is no longer a question about a single person. It is a challenge to families, schools, HBCUs, and philanthropists. It is a policy challenge: to build educational pipelines, mentorship structures, and HBCU-led medical institutions that keep Black talent from slipping through the cracks. It is a cultural challenge: to celebrate and invest in intellect and professionalism with the same intensity we invest in athletics. It is a power challenge: to shift from participation to ownership in one of the most critical sectors of our economy health care. The original article asked the question. Now, let us answer it—with vision, capital, and courage. Because if Bronny James were a doctor—and led a Black-owned hospital rooted in HBCU strength we would not just be saving lives.

We would be saving futures.