In a recent analysis published by HBCU Money, we argued that a $30 billion endowment would be sufficient to close the associate degree attainment gap between African American men and their women counterparts. The logic was elegant in its simplicity: take 50,000 African American men annually who are missing from associate degree completion, provide each with $30,000 per year—covering tuition, housing, and basic support—and the gender gap in Black post-secondary education begins to narrow. We were wrong – very wrong.

It is a compelling proposal, steeped in demographic logic and economic urgency. But elegant does not mean complete. If higher education is a pipeline, then this approach merely caps a leaky valve at the end of the conduit. The real structural deficiency lies upstream—far upstream. The associate degree gap is not born at age 18. It is the cumulative effect of educational disparities that take root as early as age 3 and metastasize through adolescence. The sobering truth is this: by the time African American boys reach college age, a significant portion have already been statistically written out of the academic script.

To reverse that fate, to genuinely provide parity in academic opportunity and outcomes for African American boys, would require not a $30 billion endowment, but a new institutional architecture rooted in Afrocentric values, collective capital, and global Black solidarity.

The Persistent Early Gap

The academic challenges of African American boys begin not in college, but in kindergarten. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), by the fourth grade, over 85% of African American boys are reading below grade level—an early indicator that portends long-term academic disadvantage. This early literacy gap is not anomalous. It is systemic and persistent.

Studies show that reading proficiency by the third grade is a leading predictor of high school graduation, incarceration, and lifetime earnings. Yet African American boys are often consigned to underfunded schools, taught by less experienced teachers, and disproportionately subjected to school disciplinary measures that remove them from instructional time. Suspension rates, for instance, are three times higher for Black boys than their White peers, often for subjective offenses like “willful defiance” or “disrespect.” The gap becomes a chasm.

In math, the picture is no better. By eighth grade, only 14% of African American boys score at or above the proficient level in mathematics, compared to over 40% of White boys. These figures reflect a system that neither recognizes nor remediates inequity early enough. If education is the great equalizer, it has yet to live up to its billing for Black boys.

The Endowment Illusion

The $30 billion associate degree endowment, calculated on the basis of a 5% annual return, yields $1.5 billion in perpetuity—enough to support 50,000 students at $30,000 per annum. Yet, that only addresses the symptom of educational inequality, not the cause. True solutions must draw from a cultural legacy of African American educational institution-building that spans from the Freedmen’s Bureau to HBCUs to freedom schools. In order to even arrive at the starting line of post-secondary education, a comprehensive educational investment must begin in early childhood and follow through until high school graduation.

Let us imagine a program that supports 50,000 African American boys per year from age 5 to age 18—a full 13-year K-12 education track. This support would include high-quality preschool, experienced teachers with cultural competency, supplemental tutoring, mental health services, STEM and arts enrichment, parental engagement programs, and college readiness support. At a conservative cost of $10,000 per student per year (a figure aligned with successful charter networks like KIPP and Success Academies), the total cost would be $130,000 per student across their K-12 experience. Multiply this by 50,000 students per cohort and you arrive at an annual outlay of $6.5 billion.

To sustain such an initiative in perpetuity with a 5% endowment return, the required endowment would be $130 billion. And this is merely to bring these students up to average outcomes.

From Parity to Excellence

Parity, however, is not the goal. African American boys do not merely need to catch up; they must be positioned to compete at the highest levels of academic achievement. That means cultivating talent pipelines that reach into gifted education, elite science competitions, top-tier university admissions, and entrepreneurial ventures.

This level of academic excellence requires not just catching up, but leapfrogging. It means summer academies at HBCUs, AP and IB course preparation, access to dual-enrollment programs, mentorship by professionals, scholarships for out-of-school opportunities, and extended learning days. According to data from the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, programs that support high-achieving students from disadvantaged backgrounds can cost between $5,000 and $10,000 annually per student, in addition to standard educational expenditures. But to leave no doubt, we must go above and beyond even the $10,000 annually.

If we allocate an additional $15,000 annually to the $10,000 base cost to foster excellence, we reach $25,000 per student per year, or $325,000 over 13 years. For 50,000 students, the annual cost rises to $16.25 billion. The endowment needed to sustain this model? $325 billion.

It is a daunting number. But it is one that puts the $30 billion associate-degree-only strategy into perspective. In reality, that $30 billion merely addresses the final 10% of the educational gap. The remaining 90% remains unfunded and unresolved.

The True Cost of a Kindergarten Cohort

To grasp the full scale of closing the education gap for African American boys, it is useful to broaden the lens beyond a cohort of 50,000 to include all Black boys entering kindergarten in a given year. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2021 American Community Survey, there are approximately 254,000 African American boys enrolled in kindergarten in the United States.

If the aim is to ensure each of these boys receives high-quality, enriched education support—costing $10,000 per year from kindergarten through 12th grade—this results in a total cost of $130,000 per child across their 13-year pre-college journey.

Multiply this by 254,000 boys and the total cohort investment requirement becomes $33.02 billion.

To maintain this annually and support each new kindergarten cohort indefinitely, the endowment would need to provide $33.02 billion every year. With a conservative 5% return, this would require a $660.4 billion endowment—just to bring African American boys to average educational outcomes.

However, as previously argued, parity is not enough. To make these boys genuinely competitive with the highest-performing demographic groups—often White or Asian boys from affluent, well-resourced districts—an additional $15,000 per year per child would be required. This would cover gifted education, STEM academies, mentoring, tutoring, and college preparation resources. The total annual investment per student rises to $25,000, or $325,000 over 13 years.

At this enhanced level of investment, the cost for the entire cohort would total $82.6 billion per year.

To generate this perpetually from a 5% return, the requisite endowment would balloon to $1.7 trillion.

This almost multi-trillion-dollar figure is not hyperbole. It is the sober arithmetic of justice. The $30 billion endowment proposed for closing the associate degree gap appears generous—until it is juxtaposed with the lifelong investment actually required to ensure those young men ever reach a college classroom. In truth, the educational equity gap for African American boys is not a $30 billion problem; it is a $660 billion to $1.7 trillion problem.

A Demographic Catastrophe in Waiting

The implications of not investing early and deeply are severe. According to the U.S. Department of Education, African American boys represent just 8% of public school students but 33% of those suspended at least once. They are also overrepresented in special education and underrepresented in gifted and talented programs.

Incarceration rates mirror educational failure. Black men are six times more likely to be incarcerated than White men. Nearly 70% of all inmates are high school dropouts. The school-to-prison pipeline is not metaphor—it is infrastructure, one built on policy choices and funding gaps.

Moreover, the economic costs compound. A 2018 study by the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce found that closing racial education gaps would add trillions to U.S. GDP. Investing in African American boys’ education is not merely a moral imperative—it is an economic one.

Philanthropy Alone Will Not Suffice

One might reasonably ask: where will $325 billion—or $1.7 trillion—come from? That sum exceeds the current combined endowments of all HBCUs by a factor of over 50. Harvard University’s endowment—at roughly $50 billion—is still only a fraction of the required amount. Relying on philanthropy alone, especially given the racialized disparities in donor patterns, would be naïve.

Instead, what is needed is a hybrid model of public-private partnerships, federal-state philanthropic compacts, and structured endowment legislation. Just as the GI Bill transformed post-war White middle-class fortunes, so too must a generational investment in Black boys be treated as a national economic priority.

Such a policy could resemble the Social Security Trust Fund model, whereby a long-term capital pool is created and invested with fiduciary prudence, returning 5% annually. Contributions could be sourced through structured community bond offerings underwritten by Black-owned financial institutions, cooperative tithing networks across African American faith communities, and revenue-sharing agreements with diaspora enterprises committed to educational reparative justice, reparations frameworks, and HBCU-aligned investment vehicles.

An African American Male Youth Education Trust (AAMYET) could be codified through legislation and act as an autonomous entity with board representation from HBCUs, Black investment firms, educational experts, and community leaders. This would ensure the governance of the fund is as transformative as its purpose.

Institutional Infrastructure: The HBCU Opportunity

Any serious endowment strategy must inevitably route through the nation’s HBCUs, which have long served as both sanctuaries and springboards for African American excellence. With their mission-focused approach, deep community trust, and track record in producing African American professionals, HBCUs are ideally positioned to be the institutional stewards of such an initiative.

Their role could include operating early college academies, developing teacher pipelines specifically for Black boys, hosting summer STEM institutes, and coordinating alumni mentoring networks. A dedicated center—perhaps named The Center for the Advancement of African American Boys (CA3B)—could operate as a national think tank, research institute, and program incubator.

This center could live at an HBCU with strong education and public policy faculties such as Howard University or North Carolina A&T, reinforcing HBCUs as hubs of cultural knowledge, economic development, and intergenerational stewardship. It would be tasked with longitudinal data analysis, best-practices dissemination, and inter-HBCU coordination. Its mission: ensure the pipeline remains robust from age 5 through 25 and beyond.

Lessons from Elsewhere

There are precedents. The Harlem Children’s Zone, under Geoffrey Canada, demonstrated the compounding power of investing in children from birth to college. The program includes parenting classes, quality pre-K, rigorous charter schooling, after-school enrichment, and college counseling. It costs upward of $20,000 per child annually but has produced impressive graduation and college enrollment rates.

Similarly, the Kalamazoo Promise—a city-funded college scholarship program—has led to higher college completion rates, especially among students of color. Yet even these models often lack national scale and sustainable endowment backing.

The Politics of Boys

There is also an uncomfortable political dimension to funding African American boys. Much of the education philanthropy and policy discourse has centered—rightly—on Black girls and women, who experience their own unique forms of marginalization. But there is hesitancy, even fatigue, in specifically addressing the needs of boys, particularly in the wake of contentious debates around masculinity and privilege.

Yet the data speak clearly. Black boys are being academically outpaced not only by their White peers, but increasingly by their own sisters. The gender gap within the African American community is growing, with 66% of Black bachelor’s degrees awarded to women. To ignore this is to risk building a one-legged stool of advancement.

The conversation must therefore be reframed—not as a zero-sum battle of genders, but as a holistic pursuit of parity. A strong, educated Black male population strengthens Black families, communities, and institutions. And a $325 billion endowment for that cause is not extravagance—it is strategy.

A Different Return on Investment

Understanding the Endowment Logic

It is important to clarify that the $660 billion and $1.7 trillion endowment figures presented are not annual funding requirements. Rather, they represent the size of a one-time, permanent endowment needed to sustainably support African American boys across generations.

Much like university endowments, these funds would be invested, and the Cooperative would spend only the annual interest income—estimated conservatively at 5%—without ever touching the principal. This means a $1.7 trillion endowment would yield approximately $82.6 billion annually, which could be used to support the full cohort of 254,000 African American boys from kindergarten through 12th grade every year, in perpetuity.

In this model, once the endowment is built, there is no need to raise another $1.7 trillion for future cohorts. Each new generation is supported by the returns of a community-built financial engine—ensuring long-term stability, intergenerational continuity, and independence from political volatility.

In financial terms, $325 billion might appear colossal. But African American communities have learned through generations that self-reliance and institution-building are more durable paths to empowerment than waiting on national consensus. The federal government has consistently underinvested in the success of African American children, and there is little indication that this pattern will meaningfully reverse.

Instead, African American institutions—especially HBCUs, Black-owned banks, community foundations, and faith-based networks—must chart a Pan-Africanist course rooted in collective economic action. Just as African American communities once built schools under Jim Crow and funded college scholarships through Black churches and fraternal organizations, so too must this generation forge a new education endowment through cooperative wealth strategies.

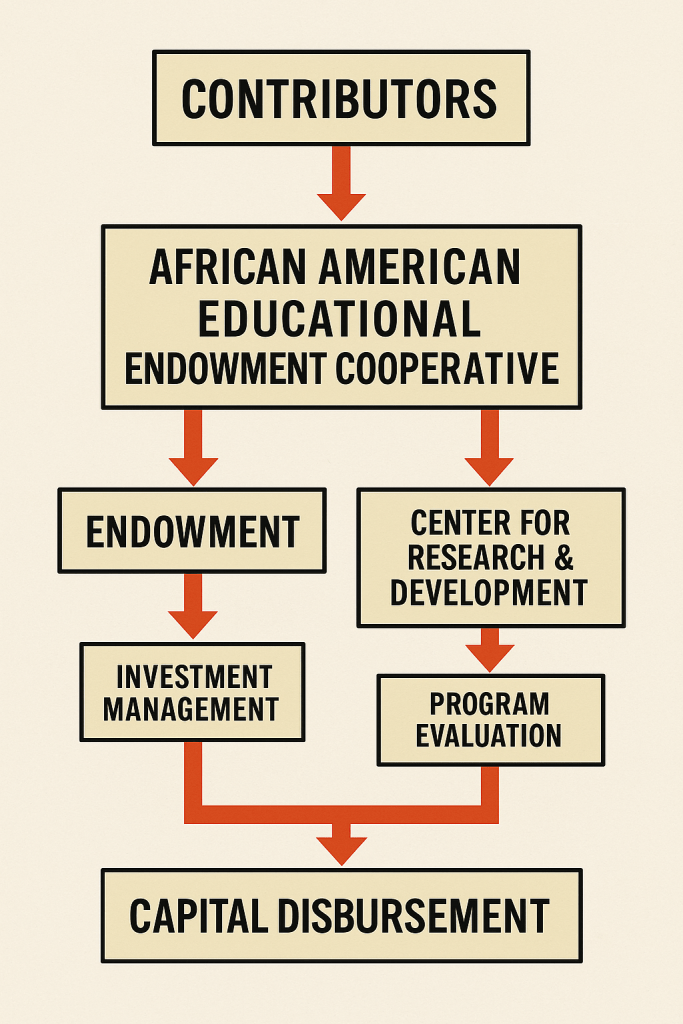

A national African American Education Endowment Cooperative could be seeded with pooled resources from HBCU alumni, Black entrepreneurs, entertainers, athletes, and Pan-African allies across the diaspora. A modest $1,000 annual contribution from one million African Americans, matched by Black institutions and philanthropic partners, would yield $1 billion annually in capital formation. With prudent investment management, even that could lay the foundation for a $30 to $50 billion fund over a generation—entirely self-directed.

Moreover, diaspora investment from African nations seeking to strengthen transatlantic ties offers another opportunity. Countries like Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa have both strategic interests and moral incentives to support African American educational uplift. A global Black education compact, co-stewarded by HBCUs and African ministries of education, could institutionalize these alliances.

The return? A generation of African American boys empowered not by charity but by communal sovereignty. Doctors, engineers, scientists, historians, entrepreneurs, and leaders grounded in African cultural capital and global competitiveness. To fund their ascension is not merely a financial imperative—it is a declaration of belief in our own capacity to shape the future on our own terms.