“Generosity without scale is sympathy dressed as strategy.”

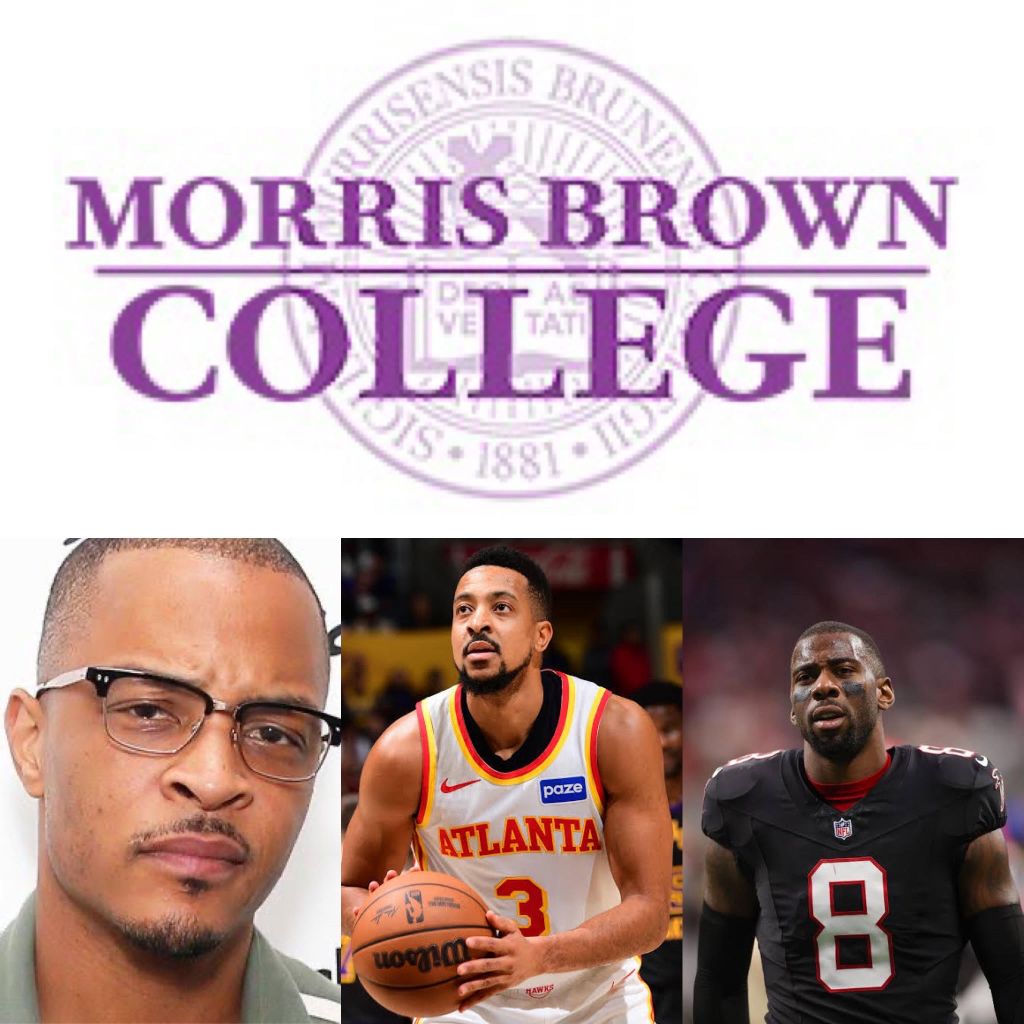

Morris Brown College, one of the oldest and most historically significant HBCUs in the country, recently made headlines when it announced $810,000 in combined donations — a $700,000 federal grant secured by Georgia Rep. Nikema Williams for emergency security infrastructure, a $60,000 contribution from the Sixth District of the AME Church, and a $50,000 personal donation from Grammy-winning Atlanta rapper TI. The timing was not incidental. Morris Brown had just been targeted with a violent racist threat sent via email to its students, the latest in a string of bomb threats and hate-driven communications that have terrorized HBCUs across the country over the past several years. In that context, every dollar matters. And TI’s willingness to write a check when the institution was under duress says something real about his character.

But character and capacity are two different things. And when we separate the two, the conversation about Black entertainment wealth and HBCU philanthropy becomes one that African America has been too reluctant to have.

A $50,000 donation to an HBCU that needs millions — preferably $10 million and above — to endow itself against continued financial stress is, by any honest institutional accounting, a gesture. It is not nothing. It is not ungrateful to say so. But let us look at what $50,000 actually produces when placed into an endowment. At a standard 5% endowment withdrawal rate, the industry benchmark used by universities from Harvard to Howard, a $50,000 contribution generates $2,500 per year or just over $200 per month in spendable income. That is assuming the donation is placed entirely into the endowment, that it is not drawn down immediately to cover operating costs, and that it compounds without interruption. $2,500 annually. That is the long-term institutional return on a $50,000 gift. It does not hire a single staff member. It does not fund a scholarship for more than a handful of semesters. It does not move the needle on the kind of structural financial distress that has kept institutions like Morris Brown on life support for decades.

For context, Morris Brown College lost its accreditation in 2002 publicly attributed to financial mismanagement, though it is worth saying plainly that what outside critics label mismanagement at African American institutions is frequently the predictable consequence of chronic resource deprivation, not a failure of aptitude. When an institution has operated for decades without the capital infrastructure that wealthier universities take for granted, the systems that sustain accreditation are not luxuries it can afford to build. Morris Brown did not regain its accreditation until 2022, twenty years of institutional limbo during which enrollment cratered to roughly 20 students. It has spent the years since clawing its way back, rebuilding systems, restoring credibility, and fighting to reopen its doors to students who had no other option. This is not a school that needs a symbolic gesture. It is a school that needs a war chest. The difference between $50,000 and $10 million is not simply a matter of degree. It is a difference in kind. One is a contribution. The other is a lifeline.

Here is where the conversation becomes difficult and where most people stop having it. The moment someone questions the size of a donation from a public figure, the response is predictable. “Well, he did not have to give anything.” “Who else is stepping up?” “At least he did something.” All of those statements are technically true. And all of them function as a wall that prevents any honest interrogation of whether the donation was calibrated to the actual need of the institution. This is the trap of philanthropic shame. It weaponizes gratitude against accountability. It makes any critique of giving patterns feel ungrateful, even when the critique is not about the donor’s character but about the structural mismatch between the scale of Black entertainment wealth and the scale of Black institutional need.

The reason to be cautious in criticizing TI specifically is not complicated either. There is always the possibility that a $50,000 donation is the first installment that the donor intends to return, to escalate, to commit over time. Philanthropic shame, if deployed too early and too harshly, can kill that possibility before it develops. No one wants to be the reason a donor who was testing the waters never comes back. So we extend the benefit of the doubt. We say thank you. And we move on to the next crisis. But extending the benefit of the doubt indefinitely is not generosity. It is passivity. And passivity is the reason HBCUs remain structurally underfunded while the entertainers and athletes who come from those communities spend their wealth in ways that have nothing to do with institutional survival.

This is the part of the conversation that makes people uncomfortable, so it needs to be said plainly. Rap music, the dominant cultural product of Black entertainment, has spent decades glorifying consumption. The cars, the clubs, the jewelry, the real estate purchased not as investment but as exhibition. The lyrics are not subtle. The messaging is not buried. It is the core aesthetic of an industry that has produced generational wealth for a small number of people while simultaneously shaping the financial identity of an entire generation of young Black men. TI himself has built a career in part on that aesthetic. His catalog includes some of the most commercially successful hip-hop of the last two decades. His business ventures span multiple industries. His net worth, by most estimates, puts him in a category where a $50,000 donation to an HBCU or African American nonprofit is not a sacrifice it is a rounding error. This is not an attack on TI. It is an observation about proportion. When someone whose public brand is built on wealth flexes in the direction of philanthropy, the question is not whether the donation is welcome. It is whether the donation reflects an understanding of what HBCUs actually need to survive. And $50,000, against the backdrop of the consumption narrative that built his brand, reads less like a philanthropic commitment and more like a line item, something that allows the story to be told without fundamentally changing the financial equation.

The case of Sean “Diddy” Combs and his reported $1 million pledge to Howard University is instructive here, though for different reasons. That pledge which Howard likely never received, and which, given subsequent events surrounding Combs, would have likely needed to be returned regardless illustrates a structural problem in how Black entertainers engage with HBCU philanthropy: the difference between a pledge and a donation. A pledge is a promise. It requires follow-through, and in many cases it does not arrive. Howard University, one of the most visible and well-connected HBCUs in the country, has publicly acknowledged the gap between pledges made by high-profile donors and funds actually received. When someone of Diddy’s financial standing pledges $1 million instead of simply writing the check, it raises the question of whether the gesture was ever truly about the institution or about the optics of appearing philanthropic. The distinction matters enormously for HBCUs. A pledge that never materializes does not pay tuition. It does not fund scholarships. It does not stabilize an endowment. It creates a false sense of security, a headline that suggests the institution has been supported when, in financial reality, nothing has changed.

TI is not alone in his absence from serious HBCU philanthropy, and that is the larger indictment. The Black entertainment and sports ecosystem has produced an unprecedented concentration of individual wealth in African American history. Athletes earning eight and nine figures annually. Musicians whose streaming catalogs generate passive income indefinitely. Actors, producers, brand ambassadors, a class of Black wealth that did not exist at this scale a generation ago. And the wealth is not abstract or distant. It is landing right in Atlanta — the same city where Morris Brown sits. Nickeil Alexander-Walker signed a four-year, $62 million contract with the Atlanta Hawks in July 2025. CJ McCollum, earning roughly $30.67 million in the final year of a $64 million contract, was traded to that same Hawks roster in January 2026. Kyle Pitts, the former fourth overall NFL draft pick, is entering free agency after completing a four-year, $32.9 million rookie contract with the Atlanta Falcons, playing his fifth-year option at $10.878 million. These are three athletes whose combined contractual wealth over recent years exceeds $190 million — all in Atlanta, all in the same city as a historically significant HBCU that just received $50,000 in a moment of crisis. The proximity is not coincidental. It is the point. The wealth is here. The need is here. The question is whether the two will ever meet on terms that actually matter to institutional survival. And yet, when we look at the philanthropic landscape of HBCUs, the contributions from this class of earners remain episodic, reactive, and structurally insufficient. The giving tends to arrive in moments of crisis, a threat, a tragedy, a headline that makes inaction look bad. It rarely arrives as a proactive, strategic commitment to institutional endowment building. It rarely arrives at the scale that would actually change the trajectory of a school’s financial health. This is not a coincidence. It is a pattern. And the pattern reveals something important about how Black entertainment and athletic wealth understands or fails to understand its relationship to Black institutional survival.

Morris Brown’s situation is a case study in reactive giving. The school was under threat. TI donated. The AME Church donated. A federal grant arrived. The headlines wrote themselves: “$810,000 in donations to Morris Brown.” On the surface, it looks like the system worked. The institution was in danger, and resources materialized. But this is crisis philanthropy, giving triggered by emergency, not guided by long-term institutional strategy. Crisis philanthropy keeps institutions alive in the short term while doing almost nothing to build the endowment depth, operational resilience, and financial sovereignty that would prevent the next crisis from being existential. For HBCUs to move beyond survival mode, the philanthropic relationship with Black entertainment wealth must shift from reactive to proactive. That means donors of consequence such as athletes, musicians, actors, entrepreneurs must begin thinking about HBCU giving not as a charitable impulse but as an institutional investment. It means committing at levels that actually move endowment needles. It means giving consistently, not just when a camera is on. It means understanding that $50,000 is appreciated, but $5 million is transformational, and $50 million is generational.

Morris Brown College needs what every structurally underfunded HBCU needs: a minimum $10 million endowment contribution to begin building genuine financial insulation. At a 5% withdrawal rate, a $10 million endowment produces $500,000 annually enough to fund several scholarships, support basic operational stability, and begin the slow process of institutional self-sufficiency. A $50 million endowment produces $2.5 million annually. That is the threshold at which an HBCU stops being vulnerable to every external shock and starts functioning as a durable institution. TI’s $50,000 is welcome. It is not unwanted, and it is not nothing. But it is not the answer to Morris Brown’s structural problem. Neither is any single donation from any single entertainer. The answer requires a collective commitment, a decision by the Black entertainers and athletes who have benefited most from the cultural and educational ecosystems that HBCUs helped build, to invest back into those ecosystems at a scale that matches the crisis.

The question is no longer whether anyone will criticize a $50,000 gift. The question is whether the class of people who can afford to give $5 million will ever decide that HBCUs are worth that investment not in a moment of crisis, but as a permanent fixture of their financial and philanthropic identity. Morris Brown College survived the threat. It received donations. But survival is not the same as strength. And until Black entertainment wealth decides to fund strength not just survival, HBCUs like Morris Brown will continue to depend on the next headline to remind donors that they still exist.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by ClaudeAI.